Perched atop the Hill of the Grasshopper, Chapultepec Castle is the only royal residence in North America. From its imperial past to the revolutionary murals inside, here’s why this must-visit landmark in Chapultepec Park is worth the climb.

Alegoría de la Revolución (Allegory of the Revolution) by Eduardo Solares Gutiérrez, 1933

They say the third time’s a charm, and on our latest (and yes, third) trip to Mexico City, Wally and I finally made it to the Castillo de Chapultepec (Chapultepec Castle).

Perched atop the summit of Cerro del Chapulín (Hill of the Grasshopper) in the first section of the vast Bosque de Chapultepec (Chapultepec Forest), this historic site and local landmark is the only castle in North America to have served as a royal residence. It was home to Emperor Maximilian I and Empress Charlotte, the ill-fated rulers of the short-lived Second Mexican Empire — but more on that later.

“Perched atop the summit of the Hill of the Grasshopper, this historic site is the only castle in North America to have served as a royal residence. ”

Chapultepec itself is one of the oldest and largest public parks in Latin America. Dating back to the pre-Hispanic era and officially designated as a public space in the 16th century, the park underwent major renovations in 1910 to commemorate Mexico’s independence centennial. Today, it spans approximately 2,100 acres — more than twice the size of New York City’s Central Park, one of the largest urban parks in the world.

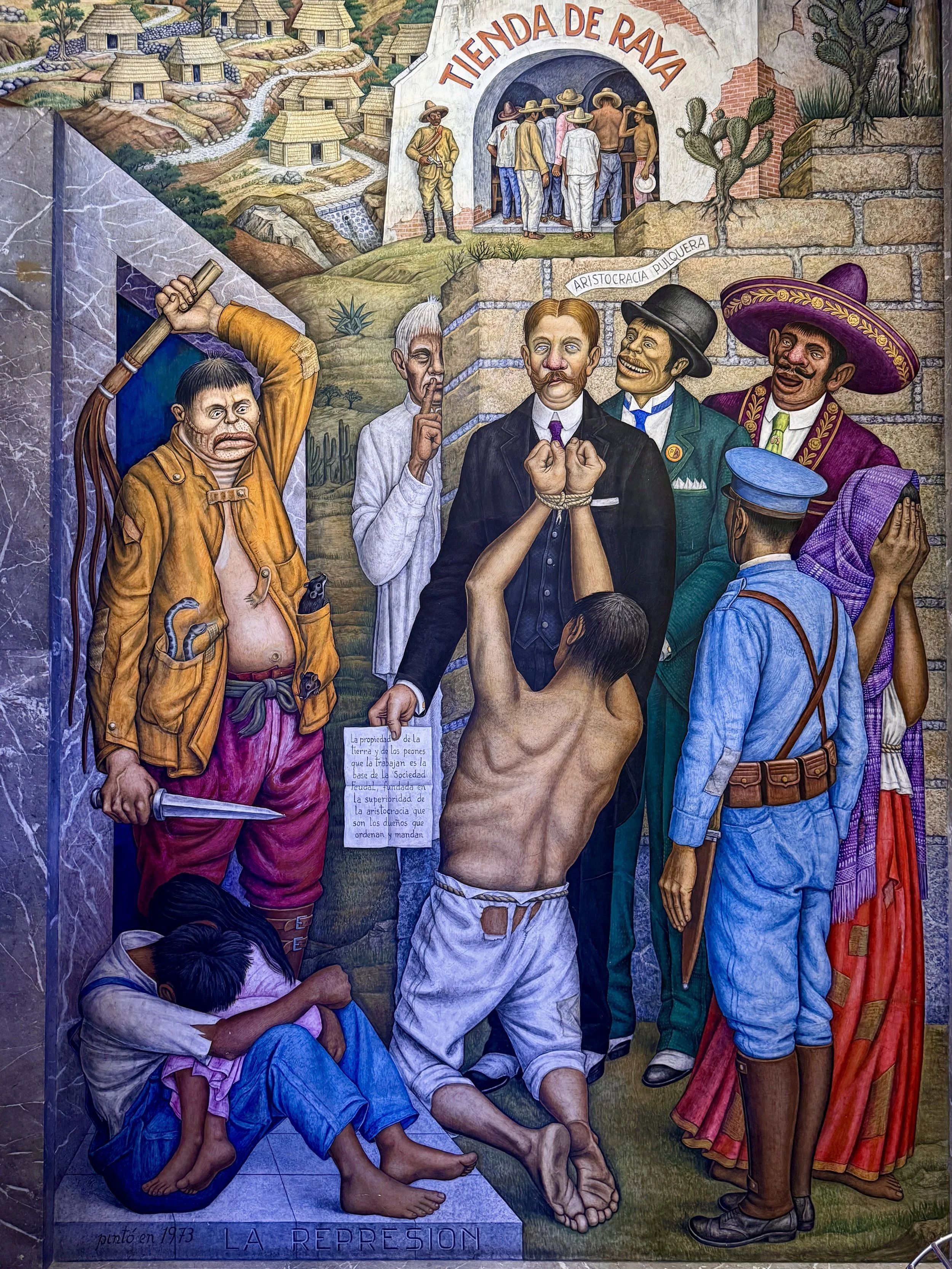

Detail of the right half of the mural La Dictadura y La Represión (Dictatorship and Repression) by Juan O'Gorman — a visual commentary on the transgressions of President Díaz

On our previous visit, we spent hours exploring the first floor of the incredible Museo Nacional de Antropología (National Museum of Anthropology), captivated by its collection of pre-Hispanic artifacts from civilizations like the Aztecs and Maya.

MORE: Explore the Museum of Anthropology’s collections on Animal Pottery and Death Cults of Ancient Mexico

The park is divided into four sections, from historic landmarks to vast green spaces. It’s home to nine major museums covering a wide range of subjects, along with monuments, gardens and countless other fascinating sights. And so far, we’ve barely scratched the surface of Section One.

Its name comes from the Nahuatl word chapoltepēc, meaning “Hill of the Grasshopper.” But why a grasshopper? The area may have once been full of them, but in Mesoamerican cultures, the insect also symbolized prosperity and good fortune.

Sarao en un jardin de Chapultepec (Festive Gathering in a Garden at Chapultepec) is a handpainted biombo, or folding screen, from around 1780-1790. It depicts a sarao, a lively social gathering featuring music and dancing that played a key role in courtly and aristocratic life.

Visiting Chapultepec Castle

For this trip, we once again stayed in Colonia Condesa, a charming neighborhood that borders Chapultepec. After breakfast, we set off toward the castle, and about 25 minutes later, we were following one of the pathways leading into the park. Since it was still early morning, the vendors were just beginning to set up.

Wally and I stopped by the Old Guard House, a brick building situated at the base of the hill, to verify our tickets with an attendant, which Wally had purchased online the night before.

You’ll know you’ve arrived at the right place when you see the Old Guard House, located at the base of the entrance leading to Chapultepec Castle.

Note: If you’re carrying bottled water or snacks like we were, be sure to pay for a locker as well. We didn’t realize that food and drink were prohibited inside the castle grounds — and were told at the security checkpoint that we needed to finish or rent a locker to store them.

The morning we visited, we got the full experience — a busload of kids arrived at the same time we did, their chaperones struggling to keep them from running and yelling as they excitedly scattered across the path ahead of us. Fortunately, we managed to get ahead of the group and for the most part avoided them once we reached the top.

We hurried past the schoolchildren walking up the hill — and mostly avoided them while exploring the castle.

As we continued our ascent to the top, where the castle is located, we passed a bronze statue of José María Morelos y Pavón, created by Spanish sculptor Ángel Tarrach. Morelos, a Catholic priest and revolutionary leader during Mexico’s War of Independence, was ultimately captured by the Spanish army, tried by the Inquisition, and executed by firing squad for treason. Despite his fate, he’s remembered as a champion of the people — a brilliant military strategist and a tireless advocate for a more just society.

A bronze statue of José María Morelos y Pavón, a priest and revolutionary leader, by Ángel Tarrac

Since there’s nowhere to buy tickets at the top of the hill, it’s essential to get them online or at the guard house before making the climb. The security checkpoint at the base of the hill won’t ask for them, but the attendants at the castle gate will. If you forget, you’ll have to trek all the way back down — and trust me, that steep uphill climb is tough enough the first time, especially if you’re still acclimating to Mexico City’s altitude. After all, Chapultepec Castle is located at a height of 7,628 feet (2,325 meters) above sea level.

Two structures stand atop the Hill of the Grasshopper: to the east, Chapultepec Castle — also known as the Alcázar (Royal Palace) — and to the west, the Museo Nacional de Historia (National Museum of History). Housed in the same building that once served as the military academy, the museum explores nearly 500 years of Mexico’s complex history that are displayed chronologically from the 15th to the 21st century.

Fun fact: The castle exterior was used as the Capulet mansion in Baz Luhrmann’s Romeo + Juliet from 1996, starring Leonardo DiCaprio and Claire Danes.

The façade of the castle that houses the National History Museum

A Brief History of Chapultepec Castle

Construction of what would become the castillo began in 1785 during the Spanish colonial period. Originally intended as a retreat for Spanish officials, the project was closely associated with Bernardo de Gálvez, the viceroy of New Spain, who governed the territory on behalf of the Spanish crown from 1785 to 1786.

Before his term as viceroy, Gálvez served as the governor of Spanish Louisiana, where he played a pivotal role in the American Revolution. He led military campaigns that supported General George Washington’s troops, capturing Pensacola, the capital of British West Florida, and effectively removing British influence from the region. His legacy lives on in the place names such as Galveston, Texas, and Galvez Street in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Unfortunately, Gálvez’s service was brief. Before he could complete the project, he died from yellow fever — known in Mexico as vomito negro because internal bleeding turned the victim’s vomit black. The estate went unfinished. By 1806, the municipal government had taken ownership of the structures, and in 1833, they were converted into the Colegio Militar, a military academy that trained young officers for the Mexican Army.

Today, the grounds are remembered as the site of the Battle of Chapultepec, a pivotal conflict of the Mexican-American War fought on September 12 and 13, 1847. The U.S. was victorious, capturing Chapultepec Castle and paving the way for the fall of Mexico City.

It was here that six young cadets, ages 13 to 19 — known as Los Niños Héroes (The Boy Heroes) — lost their lives defending the military academy against American forces in one of the war’s final battles.

The war officially ended in 1848 with the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, a humiliating agreement that forced Mexico to cede over half its territory to the United States.

Vista de la Plaza Mayor de la Ciudad de México (View of the Zócalo of Mexico City) by Cristóbal de Villapando, 1695

Exploring the National History Museum

As Wally and I stepped through the entrance of the museum, we were awestruck by the double staircase that rose before us. Covering the domed ceiling high above is La Intervención Norteamericana (The North American Intervention), a mural by Gabriel Flores. It depicts Juan Escutia, one of the six Niños Héroes who died defending the academy from invading U.S. forces. According to legend, Escutia leapt to his death from the academy, plunging over the steep rock face of the Hill of the Grasshopper, wrapped in the Mexican flag to prevent it and himself from falling into enemy hands.

The front staircase features the mural Alegoría de la Revolución (Allegory of the Revolution) by Eduardo Solares from 1934.

There’s another large-scale mural on the staircase, Alegoría de la Revolución (Allegory of the Revolution) painted by Eduardo Solares. This powerful piece depicts a moment from the revolution that overthrew the dictatorial regime of Porfirio Díaz.

Cute décor idea: a tzompantli — a rack used by the Aztecs to display the skewered skulls of human sacrifices and prisoners of war

The Conquest of the Americas

We passed display cases featuring armor worn by the conquistadors and their horses, along with a small 16th century wooden sculpture of the Virgin of Valvanera. According to legend, this likeness is a “true portrait” of the Virgin Mary, carved by Saint Luke and brought to Spain by the disciples of Saint Peter.

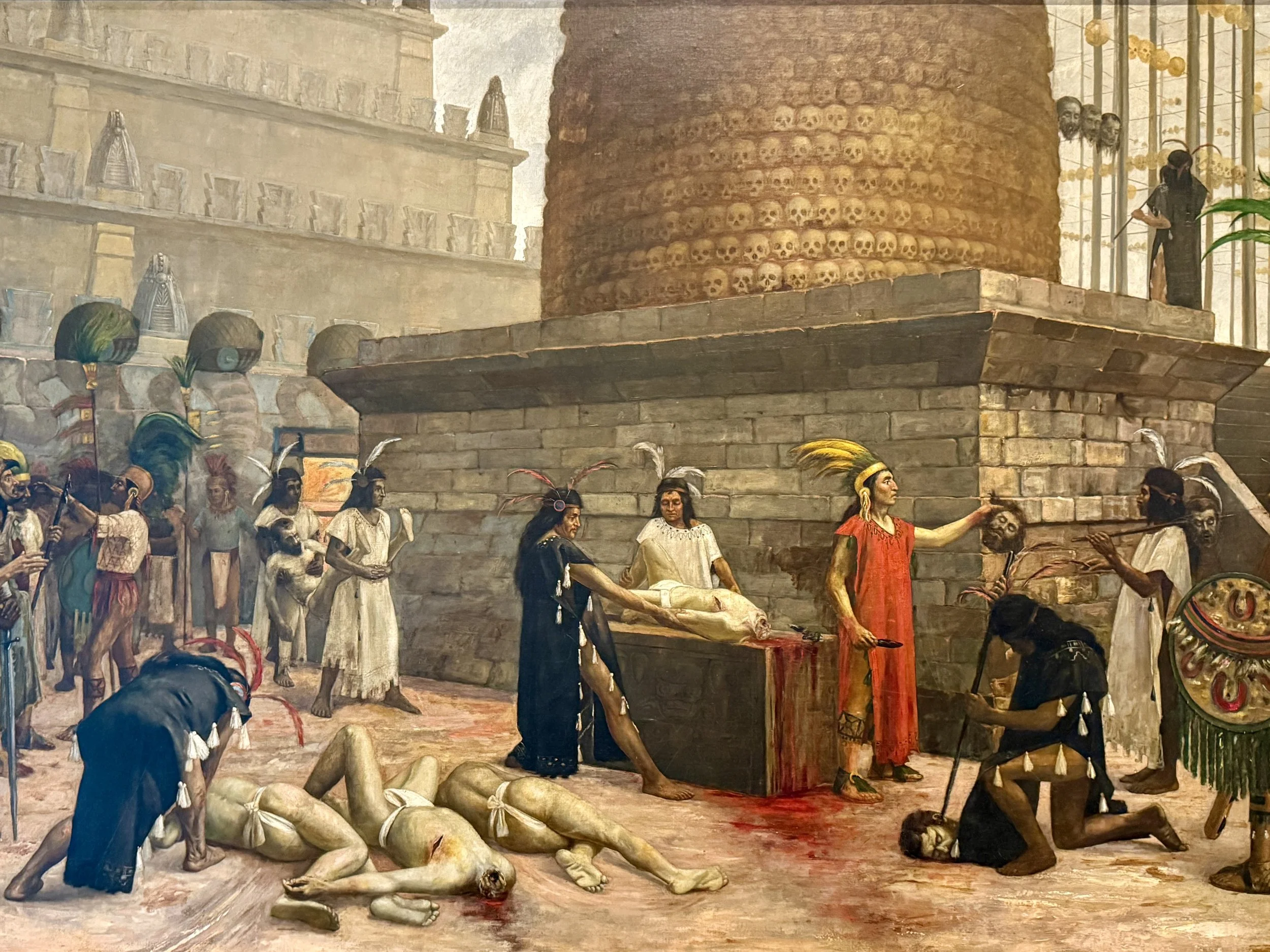

Sacrificio de Españoles por Mexicas (Sacrifice of Spaniards by Mexicas) by Adrian Unzeta, 1898

While these were fascinating, the installation that stopped us in our tracks was a tzompantli — a rack used by the Aztecs to display the skewered skulls of human sacrifices and prisoners of war. Discovered in 1994 at Tecoaque, an archaeological site in central Mexico whose name translates to “the Place Where They Ate Them” in Nahuatl, this tzompantli is believed to have been built by the Acolhua, allies of the Aztecs. It held the skulls of a defeated Spanish-led convoy captured in 1520 — comprising conquistadors and their indigenous allies, who were ritually sacrificed and quite possibly eaten.

This image, #1 De Español y Indio, Mestizo o Cholo (From Spaniard and Indian, Mestizo or Cholo), depicts the highest-class of the caste hierarchy imposed by the Spanish colonists.

The depiction of the lowest caste in #16 De Coyote, Mestizo y Mulata: Ahí te estás (From Coyote, Mestizo and Mulatto: There You Are) reflects the prejudices of the Spanish invaders.

The Pecking Order of New Spain

In a nearby room, a series of 18th century casta (caste) paintings hung on the wall.

These 16 scenes depicted the colonial social hierarchy of New Spain, a system imposed by the Spanish government to classify individuals based on ancestry and racial mixing. At the top were Spaniards, both those born in Spain (peninsulares) and those born in the Americas (criollos). Below them were mestizos, people of mixed Spanish and indigenous heritage, and other mixed-race groups, followed by indigenous people and those of African descent. Though rigid in theory, this system allowed some social mobility through wealth, marriage or official status changes.

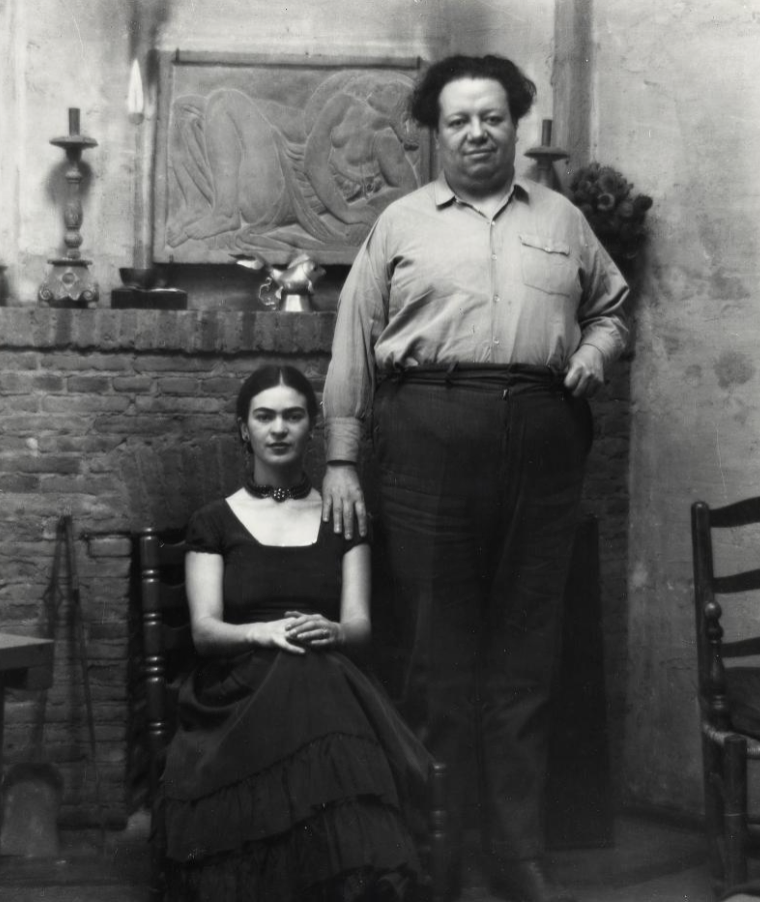

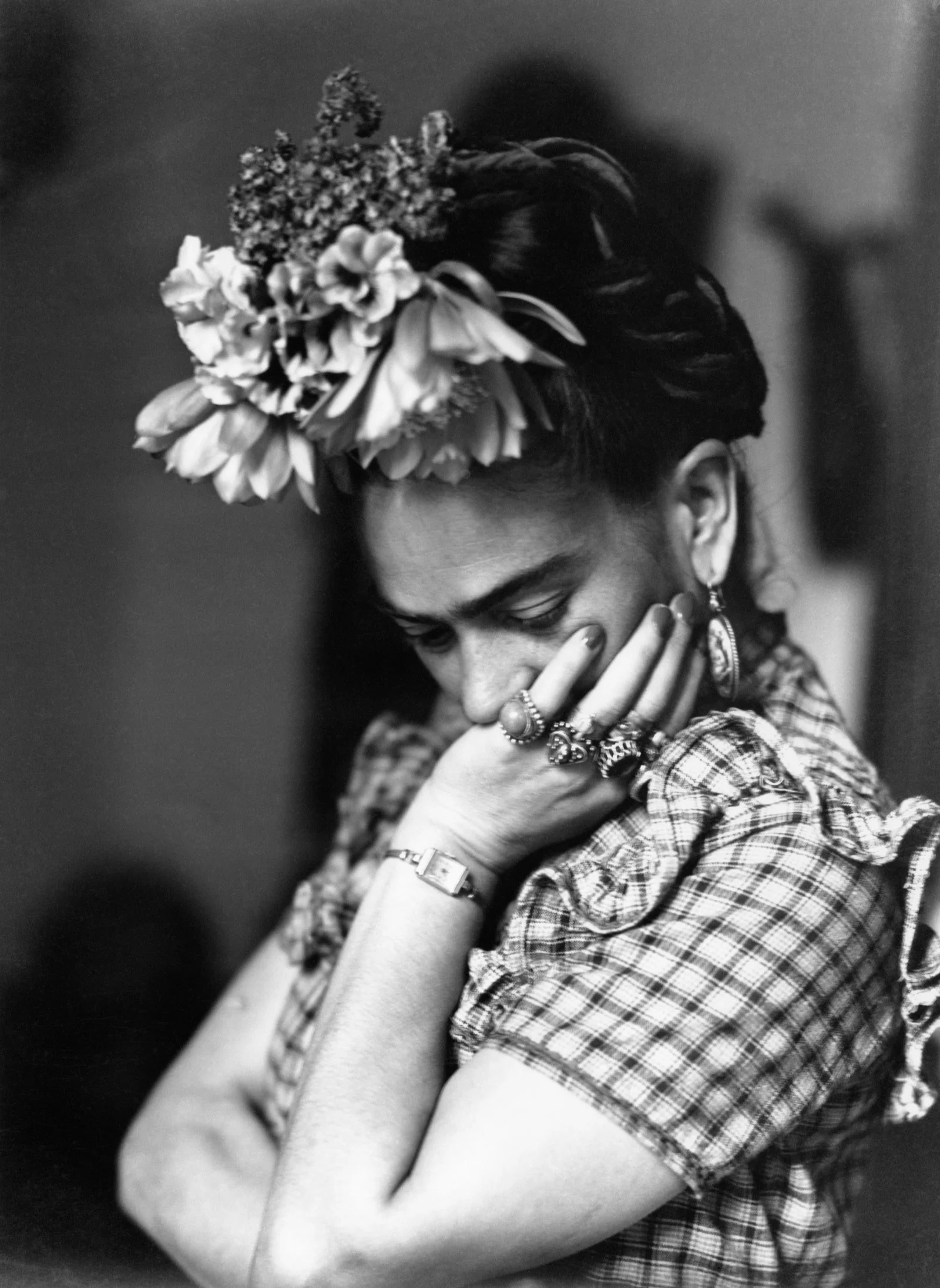

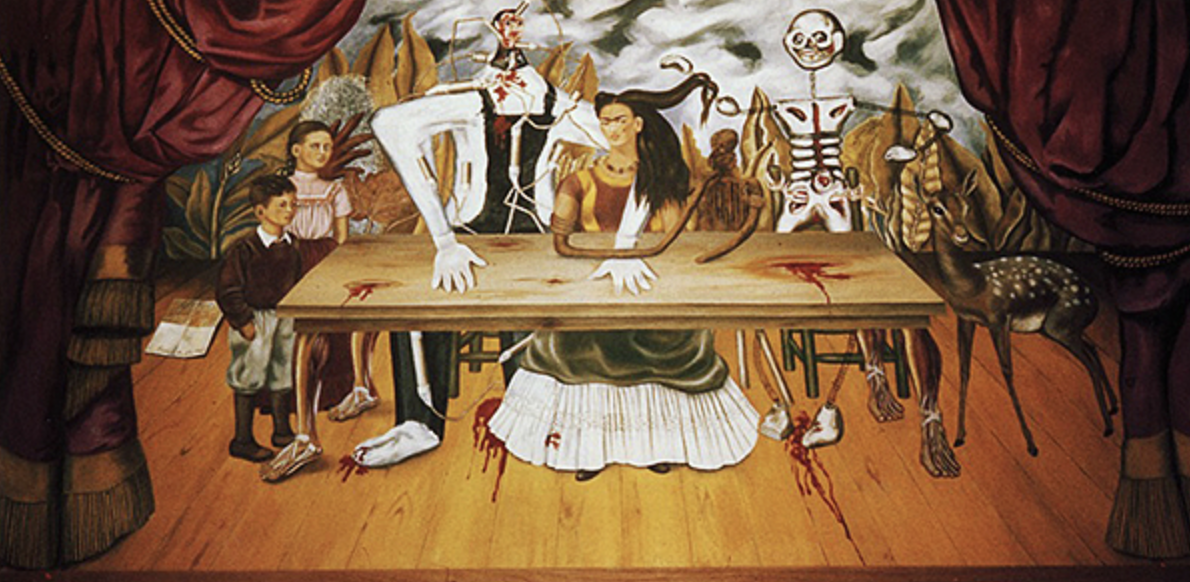

Juan O'Gorman was invited by Antonio Arriaga Ochoa, the director of the National Museum of History, to complete the project that had initially been commissioned by his friend, Diego Rivera, who had died three years earlier in 1957.

The STRUGGLE WAS REAL: MEXICO’S WAR of INDEPENDENCE

The Salón de Independencia (Hall of Independence) features the Retablo de la Independencia (Independence Altarpiece), a monumental mural painted by architect and muralist Juan O’Gorman between 1960 and 1961.

The mural is divided into four sections, each representing a different stage of the Mexican independence movement. At the center stands the white-haired figure of Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, dressed in clerical robes and brandishing a torch in his left hand. During Mexico's fight for independence, he took a banner depicting the Virgin of Guadalupe from the Sanctuary of Jesús Nazareno de Atotonilco, using it as the flag for his insurgent army. Look for the flag in the case below the mural. Hidalgo’s call to arms, known as the Grito de Dolores (Cry of Dolores), ignited the fight against Spanish colonial rule.

Nearby, José María Morelos is depicted gripping a sword, with a white bandana tied around his head. Morelos was a key leader in the movement, organizing insurgent forces to abolish slavery and the casta system.

Among other figures, Josefa Ortiz de Domínguez appears wearing a green dress and a purple rebozo (shawl), seated on a white horse and surrounded by indigenous victims of exploitation, hunger and death.

The western terrace, or Patio de Juan de la Barrera, was named in honor of one of the young Mexican cadets who died during the Battle of Chapultepec fighting in the Mexican-American War.

Pergola Terrace, or Patio de Juan Barradas

Wally and I stepped out of the building and into the sunlight-drenched western terrace. A gurgling fountain stood before us and an expansive pergola stretched out to the right, offering shade and views of the park’s artificial lake and city beyond.

At the back of the garden stands La Madre Patria, Agradecida a sus Hijos Caídos (The Motherland, Grateful to Its Fallen Children), a classical monument commemorating the Niños Héroes. Designed by architect Luis MacGregor Cevallos and sculpted by French-trained Mexican artist Ignacio Asúnsolo, it was inaugurated in 1924.

Asúnsolo finished the monument to the Niños Héroes in a mere three months, fulfilling President Álvaro Obregón’s request to have it completed and inaugurated before the end of his term.

The top of the pylon-shaped memorial features a solemn veiled matron, an eagle at her side, its wings spread protectively. Encircling them is a coiled, feathered serpent, a creature from pre-Hispanic mythology that symbolizes the deity Questzacoatl and reflects the national coat of arms. Below, four muscular figures of young native warriors clad in loincloths represent a different aspect of sacrifice and struggle, each facing a different direction: Supreme Sacrifice (east), Desperation in Defense (north), Unequal Fight (south) and The Epic (west).

The mural Sufragio efectivo, no reelección (Effective Suffrage, No Reelection) by Juan O’Gorman is named for the rallying cry of President Francisco I. Madero against the long dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz.

Fall of the Feudal Empire

When we stepped back inside from the terrace, we entered a room to the right, where a series of murals by Juan O’Gorman covered the walls. These paintings depict a turbulent chapter in Mexico’s history — the fall of the Porfirian dictatorship and the revolution that followed.

(Incidentally, O’Gorman wasn’t just a painter — he was also an architect. He designed strikingly modern homes for Frida and Diego, which pissed off the neighbors.)

One of the most striking murals, Sufragio efectivo, no reelección (Effective Suffrage, No Reelection), dominates one of the walls. Part of O’Gorman’s Retablo de la Revolución (Altarpiece of the Revolution), it captures a pivotal moment in the Mexican Revolution: the Marcha de Lealtad (March of Loyalty). At the center, Francisco Madero rides on horseback, wearing the presidential sash across his chest. The mural portrays his journey from Chapultepec Castle to the National Palace on the morning of February 9, 1913, escorted by students of the Military College. This march would mark the beginning of the Decena Trágica (Ten Tragic Days), a coup that would ultimately cost Madero his life.

Madero had risen to power in the wake of the Mexican Revolution, which erupted in 1910 against the long rule of President Porfirio Díaz. Although Díaz modernized Mexico and maintained a period of stability known as the “Pax Porfiriana,” his policies overwhelmingly favored the wealthy and foreign investors while leaving much of the population — especially indigenous communities — trapped in near-servitude. His ousting paved the way for Madero’s election as president, ushering in hopes of democracy and social justice.

But Madero’s time in power was short-lived.

The Decena Trágica was a violent siege that led to his downfall. What began as an armed revolt quickly turned into a bloody standoff in Mexico City, with intense fighting around the National Palace and the Ciudadela armory. In a devastating betrayal, Madero’s own army chief, Victoriano Huerta, turned against him. Forced to resign on February 18, 1913, Madero and Vice President José María Pino Suárez were executed just days later, on February 22, under Huerta’s orders. Their deaths threw Mexico into further chaos, deepening the revolution that would reshape the nation.

Looking into the gift shop in a central courtyard of this wing of the castle

Cannonball Run to the Gift Shop

The museum shop is located on the ground floor at the center of the Patio de Cañones (Patio of Cannons), so named for the cannons that can be found in the courtyard of the museum. The space is anchored by a sculpture by David Camorlinga dedicated to Emiliano Zapata, a key figure in the Mexican Revolution, known for championing land reform and peasant rights under the rallying cry, “Tierra y Libertad” (Land and Liberty).

The somewhat cartoonish bronze statue of revolutionary leader Emilano Zapata by David Camorlinga can be found in the Courtyard of Canons near the gift shop. The artwork captures Zapata’s defining features, including his iconic walrus mustache and broad-brimmed charro hat.

When we visited, a team was renovating the mural Batalla de Zacatecas (Battle of Zacatecas) by Ángel Bolivar from 1965.

During our visit, the whimsical and informative temporary exhibit Juárez/Max, Reflejo de dos vidas (Reflection of Two Lives) featured dioramas that told the story of the second Mexican empire, as well as the arrival and establishment of the republic, complete with cute felt Day of the Dead-style dollies of President Benito Juárez, First Lady Margarita Maza, Maximilian von Habsburg, and his wife Princess Charlotte of Belgium.

An ornate door in the Salón de Malaquitas

Green With Envy: Salón de Malaquitas

This richly decorated room takes its name from its impressive malaquita (malachite) and gilt metal doors, fountains and vases. They’re actually composed of carefully fitted slivers of malachite that combine to create the illusion of a seamless surface.

The malachite objets d’art came from Russia, purchased by Díaz from a collection shown at the first World’s Fair in 1851.

These pieces were fabricated at the Imperial Peterhof Lapidary Factory and sent by Tsar Nicholas I to showcase the artistic achievements of Russia at the first World’s Fair in London in 1851. Later, they were purchased by Díaz for the Palacio Nacional before ultimately being installed here. The vibrant green color, with their undulating bands of contrasting hues, come from naturally occurring copper carbonate deposits.

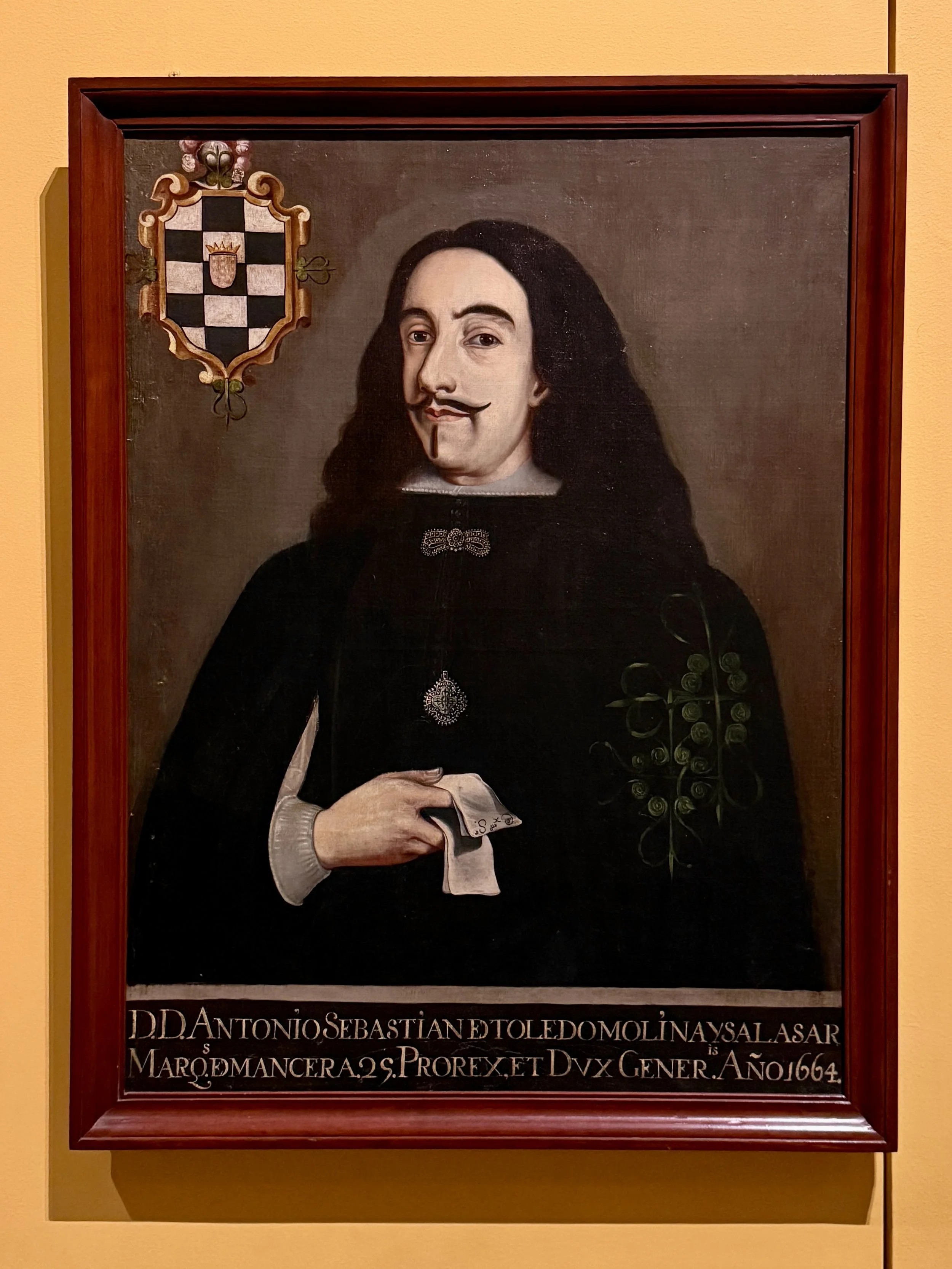

The Salón de Virreyes at Chapultepec Castle displays portraits of all 62 viceroys of New Spain. Among them is Antonio Sebastián Álvarez de Toledo y Salazar, the 18th viceroy, who served from 1664 to 1673.

Salón de Virreyes, the Hall of the Viceroys

Rounding out the museum is the Salón de Virreyes (Hall of the Viceroys), a gallery showcasing every viceroy who ruled New Spain from 1535 to 1821. It’s fascinating to see how attire and hairstyles evolved over the centuries — but the portrait that stood out most to me was of Bernardo de Gálvez, who governed from 1785 until his early death in November the next year. Created in 1796 by two friars using the sgraffito technique — derived from the Italian graffiare, meaning “to scratch” — this piece feels strikingly modern. While Gálvez’s face, hands and hat are painted, his uniform and prancing horse emerge from an intricate web of white spirals, loops and squiggly lines revealed by the “scratching” or removal of the top layer of paint.

The surprisingly modern equestrian portrait of Bernardo de Gálvez, the 49th Viceroy of New Spain, was painted in 1796 by two friars: Jerónimo and Pablo de Jesús.

This room was a fitting close to the National Museum of History as the castle’s buildings sprang forth from viceroyalty and evolved into a spectacular showcase of Mexico City’s past.

With the museum’s murals, artifacts and revolutionary history behind us, we stepped out into the sunlight once more. But Chapultepec Castle wasn’t done with us yet — next, it was on to the imperial side, where Maximilian and Charlotte once reigned in opulence. –Duke

Museo Nacional de Historia Castillo de Chapultepec

Primera Sección del Bosque de Chapultepec

San Miguel Chapultepec, C.P. 11580

Delegación Miguel Hidalgo

Mexico City

Mexico