From his massive member to a horned head, there are plenty of references to God having a corporal body in the Old Testament. Some shocking findings from “God: An Anatomy.”

Perhaps the most famous depiction of God is this detail of the Creation of Adam, painted by Michelangelo on ceiling of the Sistine Chapel.

What does God look like?

Most people nowadays probably fall into two camps: those who say God is incorporeal, an entity without form — and those who imagine him as Michelangelo painted him, a powerful if elderly man with a flowing white beard and a penchant for long white robes.

Those who think of God as bodiless haven’t paid enough attention to their Old Testament, though. In fact, the first clue is right there…in the beginning.

“So God created mankind in his own image, in the image of God he created them; male and female he created them” (Genesis 1:27).

That means God is humanlike — or should I say, humans are godlike?

It’s not so strange that God had a body. All his fellow gods did, from his competition in the Middle East to the pantheons of Ancient Egypt, Greece and Rome.

Add up all the descriptions of God in the Old Testament, and you get a red-skinned, powerfully built older man.

So what does he look like? Take all the Old Testament mentions of God, add them together and here’s what you get, according to Francesca Stavrakopoulou in her 2022 book God: An Anatomy:

A supersized, human-shaped body with male features and shining, ruddy-red skin, tinged with the smell of rainclouds and incense. His broad legs suggest he was accustomed not only to straining, leaping and marching, but sitting and standing resolutely stiff, posing like a ceremonial statue. His biceps bulge. His forearms are hard as iron. There are faint indentations around his big toes, left by thonged sandals. Beneath his toenails there are traces of human blood, as though he has been trampling on broken bodies, while the remnants of fragrant grass around his ankles suggest strolls through a verdant garden. The slightly lighter tone of the skin on his thighs indicates he was most often clothed, at least down to his knees, if not his ankles. Minute fibers of fine fabric — a costly linen and wool mix — indicate that his clothing was similar to the vestments of high-status priests. His penis is long, thick and carefully circumcised; his testicles are heavy with semen. His stomach is swollen with spiced meat, bread, beer and wine. The chambers of his heart are deep and wide. His fingers are stained with an expensive ink, and there are remnants of clay under his fingernails. On his arms are faint scars left from the grazes of giant fish-scales, and the crooks of his elbows, slightly sticky with a salty oil, bear the imprint of swaddling bands, suggesting he has cradled newborn babies. Traces of the tannery fluid used by hide-workers wind in a stripe around his left arm and down to the palm of his hand — a residual substance left by a long leather tefillin strap.

His thick hair is oiled with a sweet-smelling ointment, and shows evidence of careful styling: the hair-shafts suggest it was once separated and curled into thick ropes, while slight marks on the back of his scalp indicate it has been partly pinned beneath some sort of headgear, and his forehead is marked with the faint impression of a tight band of metal. Although his beard reaches beneath his chin, it has been neatly groomed, while his mustache and eyebrows are thick and tidy. The hair on his head and face shimmers — first dark with blue hues, like lapis lazuli, then white and bright, like fresh snow. And one glance, he has the beard of his aged father, the ancient Levantine god El; in another, it is the stylized beard of a youthful warrior, like the deity Baal. His ears are prominent, and their lobes are pierced. His eyes are thickly lined with kohl. His nose is long, its nostrils broad — the scent of burnt animal flesh and fragrant incense lingers inside them. His lips are full and fleshy, his mouth large and wide. It is at once the mouth of a devourer and a lover. His teeth are strong and sharp, his tongue is red hot. His saliva is charged with a blistering heat. The back of his throat is a vast, airy chamber, once humming with life. Below it is an opening of a cavernous gullet. Shadowy scraps of another powerful being, the dusty underworld king, cling to its walls.

The depictions of Yahweh in the Bible are disparate, but some common themes emerge.

Quite a picture, eh? All these details appear in various books of the Old Testament. Here’s a sampling.

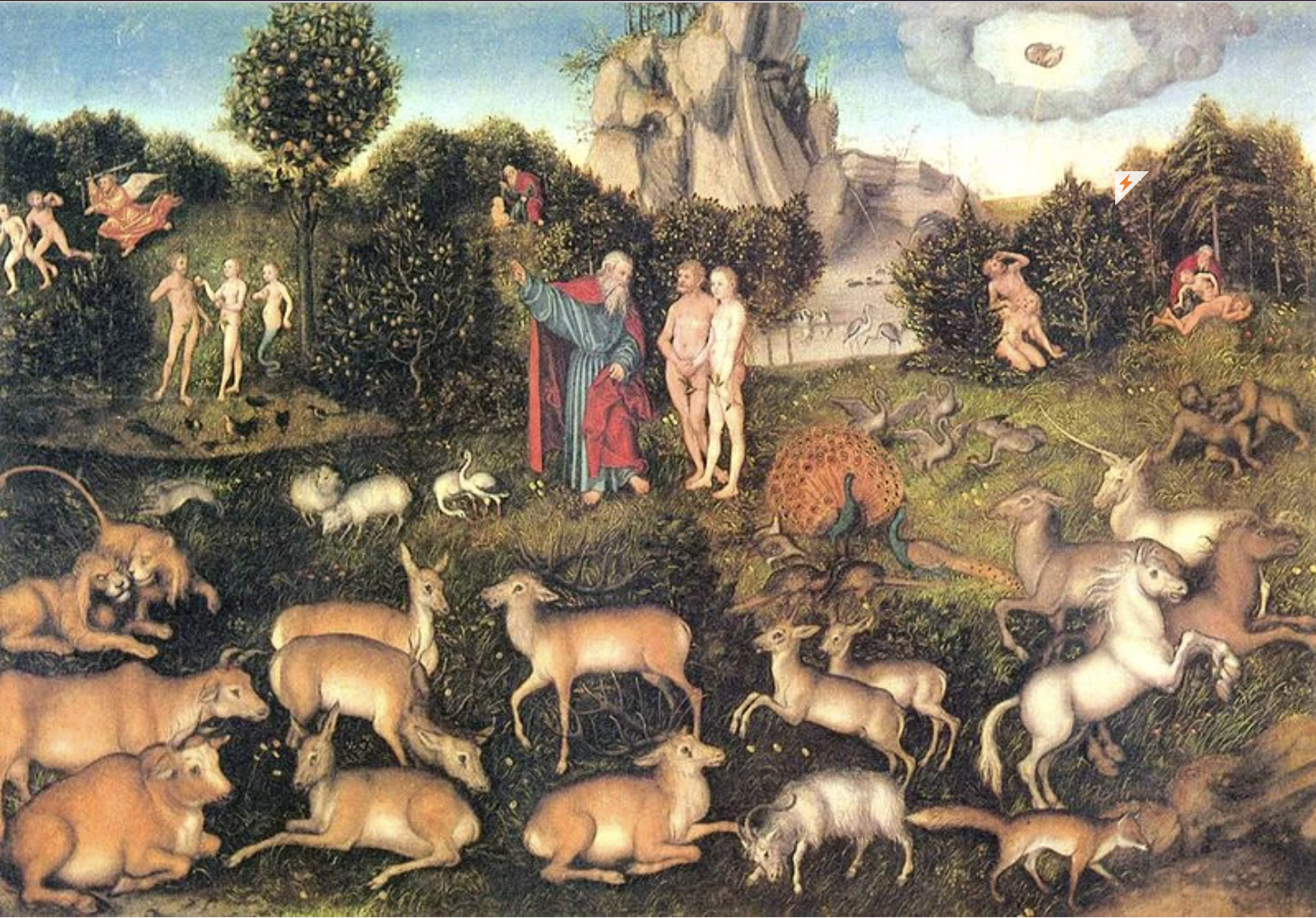

God liked to walk in the Garden of Eden with Adam and Eve … before they dared to eat of the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil.

Walking and Talking With God

Later in Genesis, Adam and Eve have eaten of the forbidden fruit and hide from God when they hear him “walking in the garden.”

Enoch, Noah and Abraham go for walks with God as well — as did Moses. Sure, God showed up as a burning bush when they first met, but after that, “the Lord used to speak to Moses face to face, as one speaks to a friend” (Exodus 33:11).

Yahweh first showed himself as a burning bush to Moses, but after a while they became good friends and would often take walks together.

Holy Shit! God’s Ground Rules

With all that walking, God had to be careful he didn’t step in something unpleasant.

When the Israelites flee Egypt en route to the Promised Land during the Exodus, God declares, “You shall have a designated area outside the camp to which you shall go; with your utensils you shall have a trowel; when you relieve yourself outside, you shall dig a hole with it and then cover up your excrement, because Yahweh your God walks in your camp” (Deuteronomy 23:12-14).

Apparently his omniscience doesn’t extend to knowing how to avoid excrement. It’s heartening to know that God steps in shit just like we do.

The prophet Ezekiel saw God in a chariot supported by hybrid heavenly creatures.

The Cherubim Chariot

After the Babylonians destroyed and plundered the Temple, the worshippers of Yahweh surely wondered if their god had also been vanquished. So the book of Ezekiel offers up a scene of Yahweh’s escape. He is seated on his supersized throne, using the Ark of the Covenant as his footstool (!). Cherubim (not the chubby baby angels you’re thinking of but four-winged celestial beings with four faces — that of a man, lion, eagle and cherub) perch upon wheels and bear the throne aloft.

You didn’t want to be on Yahweh’s bad side; he was prone to violent reactions — including stomping people to death.

God’s Stomping Grounds

But God doesn’t only walk and rest his feet. Sometimes he goes on a murderous rampage. Yahweh marches back from a massacre in the enemy kingdom of Edom: “I trampled down peoples in my anger, I crushed them in my wrath, and I poured out their life blood on the earth,” he tells a sentry in Isaiah 63:6.

“This is a god who has felt the crunch of bones and skulls under his feet; the warm, wet mulch of human flesh around his ankles; the heart spray of blood on his legs,” Stavrakopoulou writes.

In Isaiah’s vision of God, is that a massive robe filling the Temple — or something more phallic?

God’s Genitals on Display

A couple of prophets even boasted of seeing God’s oversized genitals — and yes, this is all in the Bible. Isaiah, in the middle of the 8th century BCE, entered the inner sanctum of the Jerusalem Temple, where he beheld a surprising sight.

“My eyes have seen the King, Yahweh of Hosts!” the prophet declares in Isaiah 6:1. “I saw the Lord sitting on a throne, tall and lofty! His lower extremities filled the temple!”

But the Hebrew word he used for “lower extremities” was shul, which actually means “genitals,” Stavrakopoulou informs us. (It’s worth pointing out that many scholars argue that the word actually means the hem of a robe.)

So Isaiah is saying he saw God naked — and, um, let’s just say he was impressed. I guess we shouldn’t be surprised to learn that God’s hung.

Another prophet, Ezekiel, describes a much stranger encounter: He sees God and focuses on what “looked to be his motnayim” — another Hebrew word for genitals, Stavrakopoulou writes. He looks above and below and sees the rest of the Lord’s body engulfed in flames (Ezekiel 1:27).

I’m not sure why Ezekiel seems hesitant about if he’s looking at God’s groin or not — perhaps all that fire is blinding him a bit — but heavens knows Isaiah had no doubts about what he was seeing.

The Ancient Egyptian god Min was usually depicted as having a massive erection.

‘The Imposing Erect Virility’ of the Gods

As shocking as this might seem, depictions and stories of gods having erections were common at the time these Bible books were written. A carving of the Egyptian god Min at Luxor Temple, for example, shows the fertility deity with a massive hard-on as he greets Alexander the Great.

“In the ancient cultures of southwest Asia [Stavrakopoulou’s non-Western-centric terminology for the Middle East], a sizable penis, and even its occasional overt exhibition, did not render male deities less godly, but appropriately divine. The imposing erect virility of masculine gods was vividly celebrated in these ancient societies and the religious literature they produced,” Stavrakopoulou writes. “[T]he penises of ancient southwest Asian gods embodied a conspicuous and powerful hyper-masculinity deemed essential to the ordering, fruitfulness and well-being of the cosmos and its inhabitants.”

Cain, who killed his brother, Abel, might have been God’s son, not Adam’s!

Cain’s Baby Daddy Isn’t Adam…But God?!

Most of us assume that Adam and Eve had children — but if you look at the Bible, Eve declares that Cain at least was actually the offspring of her and God: “I have procreated with Yahweh!” she shouts in Genesis 4:1.

“The more literal translation of the Hebrew is rarely seen,” Stavrakopoulou writes. “Most renderings of this verse default to a theologically fudged interpretation, so that Eve is merely presented as claiming that Yahweh has ‘helped’ her to ‘acquire a man,’ as any good fertility god might.”

Yahweh, like the Greek gods, who had sex with many unwilling women, could be prone to lust.

God as a Sexual Predator

In the book of Hosea, God not only has a body — he actually gets it on with a young woman who’s the personification of Israel.

“Here, Israel is a capricious teenager whose sexual allure so intoxicates God, he falls to scheming obsessively and possessively to make her his wife,” Stavrakopoulou writes. “‘I will take her walking into the wilderness and speak to her heart … and there she will cry out.’

“These words betray more than the romantic fantasy of a love-struck deity,” she continues. “God’s language here marks a shift from passion to threat: In claiming he will ‘seduce’ her, he uses a Hebrew expression more usually employed in the Bible to describe the rape of captive women.”

This idea of God as a sexual predator — or even just a sexual being — has been problematic for centuries, and that’s certainly true with our current sensibilities.

“Theologically, the sexual grooming and graphic violence God inflicts on his young wife is immensely difficult for some modern-day believers to reconcile with their idealized constructs of God,” Stavrakopoulou says. “But for many Jewish and Christian readers, it is more specifically the graphic portrayal of a sexually actively deity that has proved unbearable: It has been mistranslated, dismissed as ‘mere’ allegory, or simply ignored.”

Foreign books are immensely dependent upon their translations — all the more essential for the Bible, a book so many people take literally. That’s what makes this softening of the original message so alarming.

“In standard modern translations of the Tanakh [the Hebrew Bible] and the Christian Bible, the graphic sexual imagery of these troubling texts is softened or obscured with sanitized vocabulary and clunky euphemisms,” Stavrakopoulou writes.

Yahweh knew Moses couldn’t handle seeing him all in his glory — so he offered just a peek of his cheeks.

God Shows Moses His Glorious Backside

Up on Mount Sinai, Moses asks God to reveal himself: “How shall it be known that I have found favor in your sight, I and your people?” he asks in Exodus 33:16-18. “Please, show me your Glory.”

But God says that Moses can’t handle his awesomeness — he’ll only allow him to see his backside. It’s the same term used elsewhere in the Bible to describe the buttocks of an animal, according to Stavrakopoulou.

God adds that no mortal could gaze upon his face and live. “In its narrative context, it is a capricious assertion, for Yahweh and Moses have already enjoyed a number of conversations ‘face to face’ — and Moses has survived,” Stavrakopoulou points out.

Like other deities of the Middle East, Yahweh’s body is engulfed in a dazzling aura: He is “wrapped in light as with a garment” and “clothed with glory and splendor.”

It’s all too easy to think of these descriptions as hyperbolic — but they’re meant to be taken literally, Stavrakopoulou asserts.

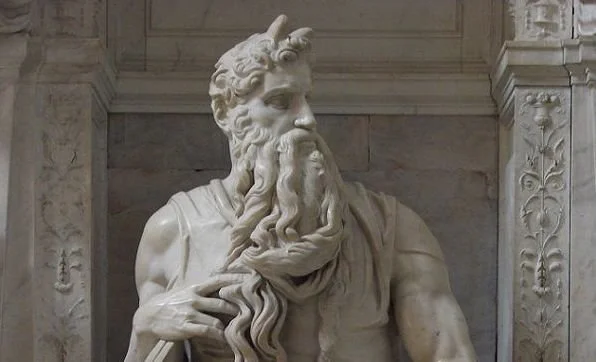

Whether they were literal or beams of light, Moses came back from a convo with God bearing horns.

The Glory of God Makes Moses Horny

“In Exodus, however, God’s luminescent backside clearly gives off something more powerful than a wondrous afterglow. When Moses finally descends from the Holy Mountain, clutching the Ten Commandments, his own face is startlingly transformed,” Stavrakopoulou writes. “But quite how is a matter of some debate, for the ancient Semitic root of the Hebrew term used to describe this transformation probably means ‘horn,’ but is also associated with light. The earliest translations of this peculiar story indicate that, from at least the 3rd century BCE, Moses was understood to have developed horn-like rays of light, so that his face beamed with a divine radiance. Other ancient scholars would assume Moses’ face literally grew horns — a symbol of the divine elsewhere in the Bible — giving rise to startling medieval images of Moses as a double-horned being. Either way, Moses undergoes a bodily transformation so profound that the Israelites cannot look him in the face and are afraid to go near him. Moses’ visual encounter with God has left its mark on him, rendering him more divine than human.”

Poor Moses never entered the Promised Land — but was it God who took the care to bury him?

God the Gravedigger

Moses seems to have been the Old Testament character with the most face time with God. And that lasted right up until the moment of his death. The poor guy — being a favorite of Yahweh doesn’t get you much. Moses dramatically led the exodus of escaped Israelite slaves out of Egypt, delivered the Ten Commandments and wandered the desert for 40 years. Finally, the time has come to enter the Promised Land. But, in a shocking twist, God shows Moses the beautiful sight of their hard-earned payoff — and then tells him to literally drop dead: “Moses, the servant of Yahweh, died there in the land of Moab, at Yahweh’s command. And he buried him in the valley in the land of Moab” (Deuteronomy 34:5-6).

“In the book of Deuteronomy, Moses’ gravedigger is God himself,” Stavrakopoulou writes. “Appalled by the idea that God could contaminate himself with the impurity of a corpse — even the corpse of so holy a man as Moses — some Jewish and Christian translators corrected what they perceived to be an error in the text: ‘he buried him’ simply became ‘he was buried’ or ‘they buried him,’ leaving generations of readers to assume that mourning Israelites or weeping angels had performed Moses’ mortuary rites, rather than God himself.”

Baal, one of Yahweh’s biggest rivals in the ancient Middle East

God Gets Horny

It’s an image that wouldn’t sit well with most modern Christians or Jews — especially given its connections to the Devil and demons — but one of the earliest descriptions of God describes him as having horns. “God, who brought [Israel] out of Egypt, has horns like a wild ox!” the prophet Balaam declares in Numbers 23:22.

“In the Western imagination, a horned being tends to conjure images of the diabolical, and the grotesque. From the man-eating bull-headed Minotaur of Greek myth to the cloven-hooved goat-faced Devil of Christianity, horns have long served as a hallmark of horror,” Stavrakopoulou writes. “But in the world of the very ancient gods, horns were the most prestigious and alluring manifestations of divinity, and most deities would be equipped with them.”

Horns were a sign of power, designating that the gods who sported them “were beings of bullish virility and ferocious strength,” Stavrakopoulou explains.

There’s a horrific description of a fiery God — right before he gobbles up a roasted king of Assyria.

The Nose Knows: God’s Wrath and a Kingly BBQ

“The God of the Bible was particularly proud of his nose,” Stavrakopoulou tells us. “In his lengthy monologue on Mount Sinai, he reels off a list of his best qualities, not only describing himself as merciful, gracious and abounding in steadfast love and faithfulness, but ‘long-nosed,’ too.”

This is a way of saying he has deep nostrils, she says — meaning slower breathing, and by extension, being patient and slow to anger.

But once that temper raged, you didn’t want to be anywhere near him.

In the book of Isaiah, a seer spies Yahweh in the distance, his nose ablaze, “his lips full of fury, his tongue a devouring fire; his breath an overflowing stream, reaching up to the neck!” (Isaiah 30:27-28).

What’s God up to? Oh, just sacrificing an Assyrian king upon a pyre and feasting on his charred corpse.

The ancient Levantine deity El

The Ancient Almighty: God’s Golden Years

Our current image of God as a powerful older man comes from a portrayal in Daniel 7:9-10 from the 2nd century BCE. As Stavrakopoulou states, “God himself remains a picture of perpetual purity: Enthroned, in fiery splendor, and surrounded by thousands of divine courtiers, he is called ‘an Ancient of Days,’ dressed in robes ‘white as snow,’ with hair ‘like a lamb’s wool.’”

Again, this iconography is borrowed from neighboring deities, including El, whom Stavrakopoulou describes as Yahweh’s father — before Yahweh was retrofitted as the sole true god. El’s (and Yahweh’s) gray hair and beard were seen as signs of immortality and wisdom.

Unseen and Unsculpted: The Theological Dance Around God’s Corporality

When thinking about this article, I realized something that shocked me: While I’ve seen a few paintings of God — Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel depiction of God (looking suspiciously like Zeus) reaching out to Adam springs to mind — I couldn’t think of a single sculpture of him.

Part of this is due to the fact that the mentions of God as having a body in the Bible make many Christians uncomfortable. They want the only depiction of God as corporeal to be that of Jesus.

“Those troublesome verses in the scriptures attesting to God’s body would be smoothed, smothered or superseded by new interpretive frameworks and some fancy philosophical footwork,” Stavrakopoulou writes. “A favorite tactic employed by early Christian theologians was simply to reduce all biblical references to God’s body to the symbolic.”

Even further back than that, after the Jerusalem Temple had been rebuilt in the 5th century BCE, Yahweh’s worshippers understood all too well the vulnerability and lack of transcendence of a corporeal god.

It was around this time one of the Ten Commandments became “You shall not make for yourself a carved image.”

Once a vividly described giant, God lost his body.

Are there few statues of God because one of the Ten Commandments forbids “carved images”?

And therein lies the main controversy around God: An Anatomy. The book has ignited a theological firestorm, dragging Yahweh off his lofty pedestal and into the gritty, grimy realm of human physicality. Some scholars are applauding Stavrakopoulou’s daring approach, while others are reaching for the nearest exorcism manual.

Biblical scholar Joel Edmund Anderson isn’t holding back. On his blog, Resurrecting Orthodoxy, he accuses Stavrakopoulou of having a “tin ear to the literary artistry and nuance of the biblical texts,” arguing that her interpretations are overly literal and lack proper contextual grounding.

So, even though many Christians believe everything in the Bible to be literal, they prefer to skip over references to God’s form — it’s all too close to those pagan deities. Team Symbolic has won out; no one really talks too much about God’s body nowadays. It seems that the divine anatomy lesson is one lecture most would rather miss. –Wally