A room-by-room tour of the UNESCO World Heritage masterpiece in southwestern Pennsylvania, where nature and modern architecture coexist in breathtaking harmony. Plus: What a place to skinny-dip!

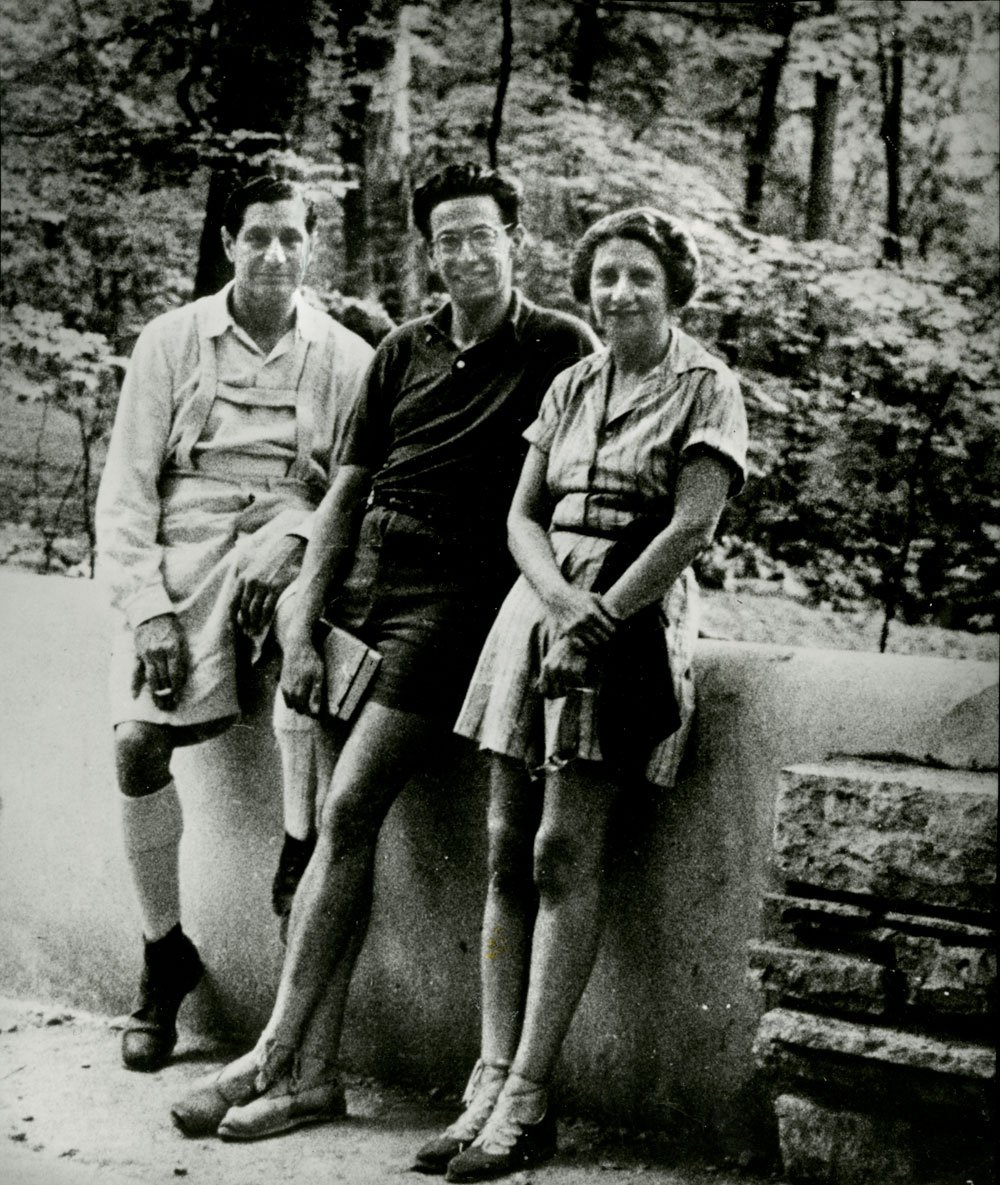

Duke and Wally pose by the aptly named Iconic View of the home. The cantilevered terraces unite the indoor and outdoor spaces, blurring the lines between nature and architecture.

Every summer, my parents visit Wally and me in Chicago for a long weekend. We always have a great time together, and this year we decided to mix things up by taking a short trip to Pittsburgh. The four of us had already toured two of Frank Lloyd Wright’s residences, the Martin House in Buffalo and Graycliff in Derby, New York. We chose Pittsburgh because of its proximity to Fallingwater, and since my parents were driving, we set aside a day to experience it together.

The rushing waters of Bear Run stream were especially feisty after the rain.

Pro tip: Get there early and explore the grounds. When we checked in at the Fallingwater Visitor Center kiosk, one of the staff members provided us with a map and suggested we visit the Iconic View platform. She informed us that it wasn’t part of our tour — and we were glad we made the trek to see it. It’s a short 10-minute walk down the trail to the aptly named viewing platform, which is easy to follow and accessible to most people. This is the money shot folks, and we guarantee that you’ll appreciate the stunning views of Fallingwater, the waterfall and the surrounding landscape.

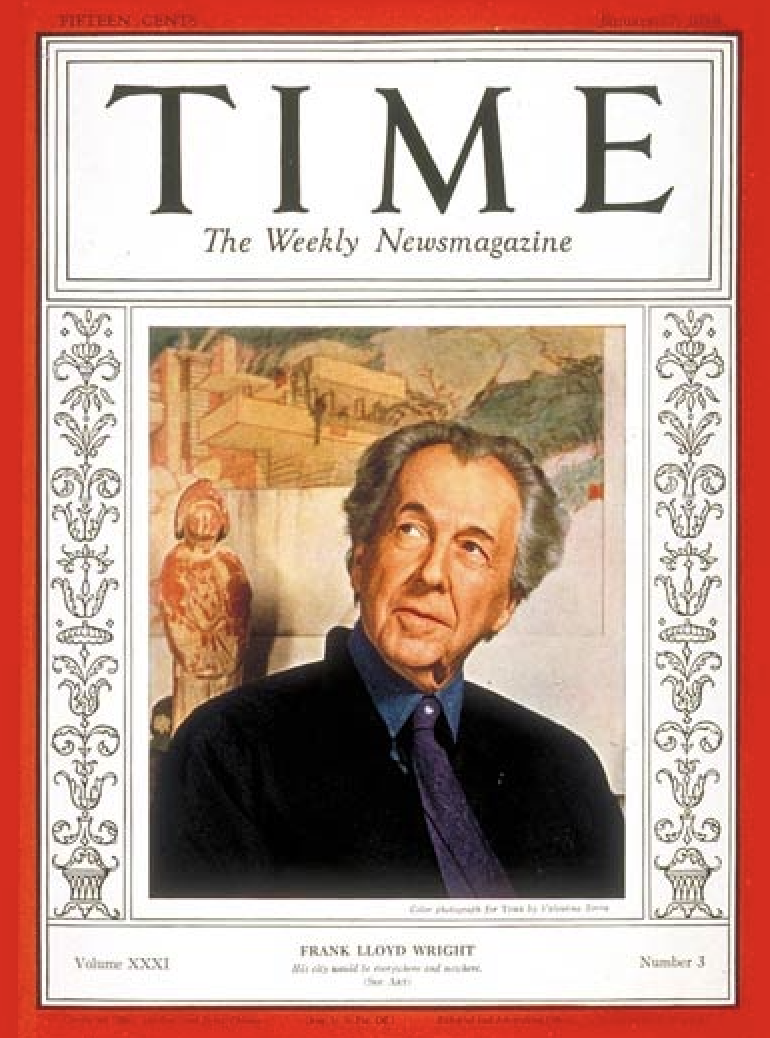

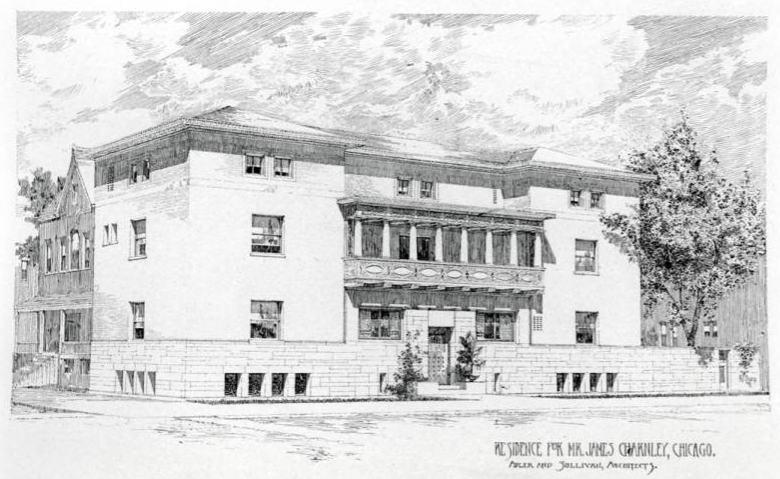

LEARN MORE ABOUT THE ORIGINS OF FALLINGWATER, from the geological inspiration to the friendship between Edgar J. Kaufmann and Frank Lloyd Wright.

The Edgar J. Kauffman Sr. Residence aka Fallingwater looks picture perfect from any angle. The color of the terraces and the bridge were chosen by Wright to match the underside of a dying rhododendron leaf, or sere.

Fallingwater: The House That Wright Built

As we rounded the bend in the gravel path the sound of rushing water intensified and filled our ears. There, nestled among the abundant native rhododendrons and trees, was Fallingwater. Perched on a precipice above a rushing waterfall, the historic weekend retreat built for the Kaufmann family was even more awe-inspiring in person than I had imagined. Its cantilevered terraces appeared to float, extending outward like a precarious stack of Jenga blocks moments before toppling.

The original budget for Fallingwater was $35,000, but the final cost (including the guesthouse) ballooned to $155,000. To put this in perspective, an average house cost $5,000 to build in the late 1930s.

We paused on the concrete bridge leading to the main house and stopped to listen to our guide, Rod, who directed us to look at the plunge pool with the bronze sculpture Mother and Child by French artist Jacques Lipchitz set on the edge of the low stone wall enclosing it.

He explained to us that the Kaufmanns liked to get up in the morning and take a dip. Bear Run isn’t a swimming stream, so they would walk down the steps descending from the hatch in the living room and wade into the 4.5-foot-deep pool. Fed by a freshwater spring, its waters remain a brisk 55 degrees Fahrenheit (12 degrees Celsius) year-round. In fact on her first day at Fallingwater, Elsie Henderson, a Black woman who worked as a cook for the Kaufmann family, got an eyeful. She heard laughter from the kitchen window. When she looked outside she saw Edgar J. Kaufmann, Sr., his wife Liliane, and their guests frolicking in the chilly waters nude and remarked “what have I gotten myself into!”

The bronze sculpture Mother and Child by French artist Jacques Lipchitz depicts a legless mother with a child clinging to her back. It holds pride of place at the plunge pool.

We continued our walking tour and followed Rod to the back of the house, where the main entrance is concealed beneath a rectangular trellis covering the carport. This was by design: Wright wanted the Kaufmann’s to feel sheltered and secure.

Fallingwater’s kitchen was so renowned for its ultramodern features and functionality that many suppliers were eager to promote the use of their products at the residence.

Fallingwater’s Kitchen of Tomorrow

Before our group entered the main house we took a detour to the kitchen. Although small by today’s standards it was both functional and beautiful. Wright considered the kitchen to be a workspace, not a gathering place for the family. It was run by the indefatigable Elsie Henderson from 1946 to 1964, when the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy took over the house.

After working for the Kaufmanns, Henderson went on to cook for the Kennedys in Hyannis Port. She returned to Pittsburgh to live out her life and passed away there in 2021 at the age of 107!

Henderson had an unobstructed view of the West Terrace, which features a cast iron Sung Dynasty (960-1279) Buddha head purchased by the Kaufmanns in 1951. Wright supposedly chose its placement himself.

The house was completed in the mid-1930s and its kitchen featured modern amenities that were considered modern at the time. For example the countertops and Wright-designed work table were made of Formica, a recently patented laminate material. Kaufmann Sr. learned about it earlier than the general public because it was invented by engineers at Westinghouse Research Laboratories in 1935. The floor is made up of custom colored rubber tiles in Cherokee red, one of Wright’s signature colors.

The goldenrod enameled steel cabinets in the kitchen came from St. Charles, an Illinois-based company that specialized in factory-made modular units and the preferred choice of Wright. St. Charles was a popular brand at the time, and were known for their high quality and durability.

The kitchen also included a turquoise-lined Frigidaire refrigerator, a Kitchen-Aid dishwasher, double sinks, double warming trays and a wood-burning AGA Range Cooker, a technological marvel from Sweden and the invention of the Nobel Prize-winning physicist, Gustaf Dalén.

If you can’t stand the heat, get out of the kitchen. The wood-burning AGA Range Cooker at Fallingwater was always radiating heat, which was probably not very pleasant in the summer.

AGA stoves were very expensive, but they were also very efficient. The stove had to burn all the time, and it didn’t have knobs or settings to adjust the temperature.

Eventually Henderson complained about the amount of heat radiating from the stove and the Kaufmanns had it replaced with an AGA electric model.

The best seats in the house have a pair of earthenware wine decanters on either side of the built-in living room sofa.

Compression and Release: Entering the Living Room

The Kaufmanns kept a collection of walking sticks outside for guests to use on hikes. After their walks in the woods, guests could return to the house to wash their hands and feet at the small basin located between a pair of Pottsville sandstone support columns outside the entrance.

Rod pointed out that we were being compressed before being released into the living room, a technique that Wright was well known for. As our group entered the monumental room, we immediately felt a sense of release. The open 1,800-square-foot interior space is the ultimate family gathering space. It has a central, symmetrical raised cove ceiling that uses diffused indirect fluorescent tube lighting. Edgar jr., the only son and child of Edgar J. Kaufmann, Sr., (E.J.), and Liliane, had seen this type of lighting used in a commercial application and requested that Wright integrate it into the design.

The living room also has a dining nook with a built-in table . Although it’s set for four, it could be extended using leaves stored in the buffet behind it.

Rod explained to us that everything inside Fallingwater is original to the Kaufmanns’ use of the home. Many of its objects and furnishings came from their eponymous Pittsburgh-based department store.

The Kaufmanns collaborated with the best suppliers in the country to create a truly unique home. Pittsburgh Plate Glass (PPG) rushed in the glass, while Armstrong supplied the cork flooring and wall tile — both firms headquartered in Pittsburgh. DuPont supplied the paint, Dunlop the foam rubber, Thrush the heating and Hope’s the steel window frames.

To keep unwanted hands off Fallingwater’s treasures, Rod asked our group to avoid leaning against, sitting on or touching anything inside the house.

He added that we’d be using the stairs and since Fallingwater was built before building codes, they’re aren’t any railings. With this in mind, visitors are allowed to use the ledges above the exposed sandstone walls to safely navigate the interior staircases.

Victor Hammer’s The Excursion, an oil portrait of E.J. as a hiker, with a walking stick, commissioned by Liliane in 1929 hangs opposite the dining room table.

There’s a music alcove near the entrance where the Kaufmanns would listen to records on their Capehart stereo turntable, and a reading alcove where they could sit and read. E.J., Liliane and Edgar jr. were academics who enjoyed spending time in their home surrounded by music and books.

The mod-looking Wright-designed banquettes are where the Kaufmanns would listen to music. Note the cabinet to the left that stored the turntable and records.

Facing the windows is a wood library desk designed by Wright and built around one of the room’s stone support columns. It’s a masterpiece of design, and incorporates all four of the main design motifs found throughout the house: horizontal lines, cantilevers, circles and semi-circles. There’s even a lozenge-shaped shelf that echoes the shape of the hatch behind the desk, which leads down to the stream.

While designing Fallingwater, Wright dictated that no rocks or boulders were to be destroyed or removed. His profound respect for nature resulted in a home that’s beautifully integrated into its natural surroundings. The boulder that forms the foundation of the house was incorporated into the room and serves as the hearth. Wright was quoted as saying, “The rock on which E.J. sits will be the hearth, coming right out of the floor, the fire burning just behind it.”

The hearth of Fallingwater with one of the original wooden stump stools used by the Kaufmanns serves as a mini bar.

A round, Cherokee red kettle hangs on the left side of the fireplace, nestled into a concave indentation that fits it perfectly. It was meant to swing out over the fire to serve mulled wine, however it was ultimately relegated to being a conversation piece since the metal was so thick it took 10 hours to heat up.

The spherical cauldron is pretty to look at, but not so great at heating mulled wine. The wrought iron fireplace trident was forged by master metalsmith Samuel Yellen, and is from La Tourelle, the main Kaufmann residence in Fox Chapel, Pennsylvania.

In the dining area, Wright designed the built-in dining table and incorporated leaves into the sideboard that can be attached to the table to accommodate additional guests. Wright had wanted to pair the table with his more formal Barrel Chair, but Liliane prevailed, having purchased rustic three-legged wooden peasant chairs at a second-hand shop in Florence, Italy, which she felt were more appropriate for their country retreat.

Although Wright lost that battle he did design additional custom pieces for the living room, including occasional tables, banquettes, and zabutons (low wood-framed footstools) upholstered in warm hues of golden-yellow and red-orange. The zabutons represent one of the earliest uses of latex foam, a material suggested by Edgar jr.

Wright’s free-floating elements were easy to move around and, most importantly, never blocked the view of nature outside. And many were made of wood, which the architect described “as the most humanely intimate of all materials.”

To give the flagstone floors throughout the house a wet look, Wright specified Johnson’s Glo-Coat, a wax that created a glossy sheen — drawing a parallel to the river rooks of the stream below. Wright chose that product because he was commissioned to design the Johnson Wax Building in Racine, Wisconsin while completing Fallingwater. Talk about product placement!

Our guide Rod sharing stories with our group about Fallingwater.

After our group had finished exploring the room, Rod shared an interesting story with us about a visitor he had on a previous tour who said, “In 1956, I was a Boy Scout in a local troop here.” A freak tornado had hit the area, and a debris jam built up, causing the stream flowing beneath Fallingwater to overflow into the first floor of the house. “After the flood, Edgar Sr. invited our troop in to help clean up as a service project,” the man has said.

The visitor went on to explain that Elsie Henderson fed them, and they placed their sleeping bags on the floor of the living room. He continued, “I slept on that rock there,” pointing to one of the waxed flagstones.

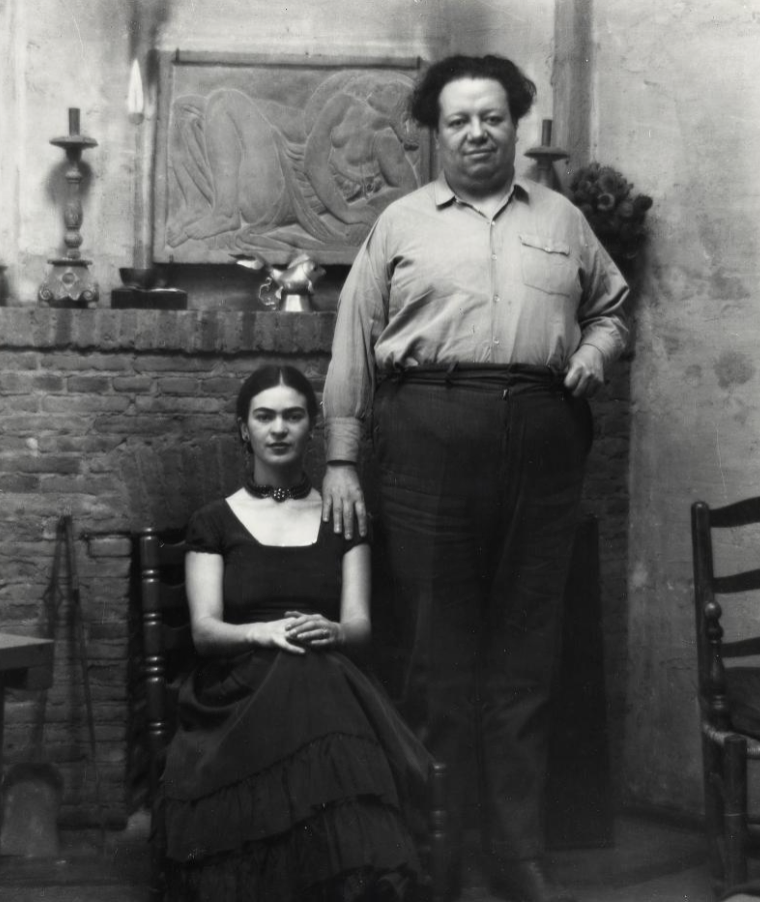

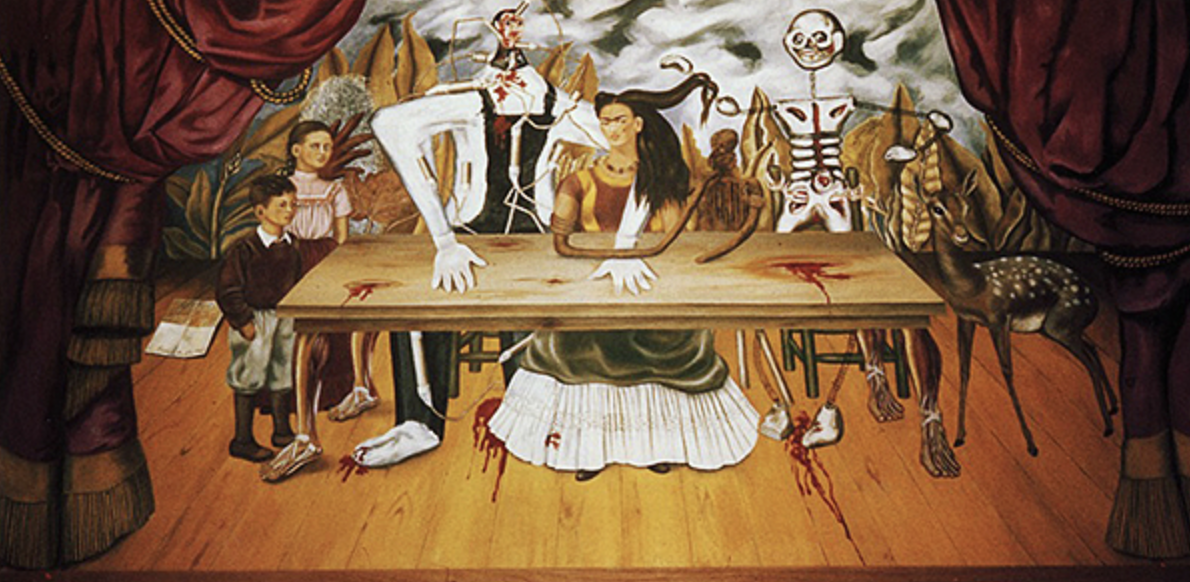

The guest bedroom at Fallingwater includes a chromed-metal carafe by the American Thermos Bottle Company and a conté crayon drawing by Diego Rivera.

The Guest Bedroom

We followed Rod up the narrow stairwell that led to the second floor. There are a total of four bedrooms in the main house. Each has its own bathroom, private terrace and fireplace, with the exception of the guest bedroom. The headboard is large enough to accommodate two beds, but because the room is quite small, one bed was removed to make room for tour groups.

On the wall is Profile of a Man Wearing a Hat, a Conté crayon drawing by Mexican muralist Diego Rivera. This is the only room in the whole house with blinds because Liliane’s private terrace can be seen outside the window.

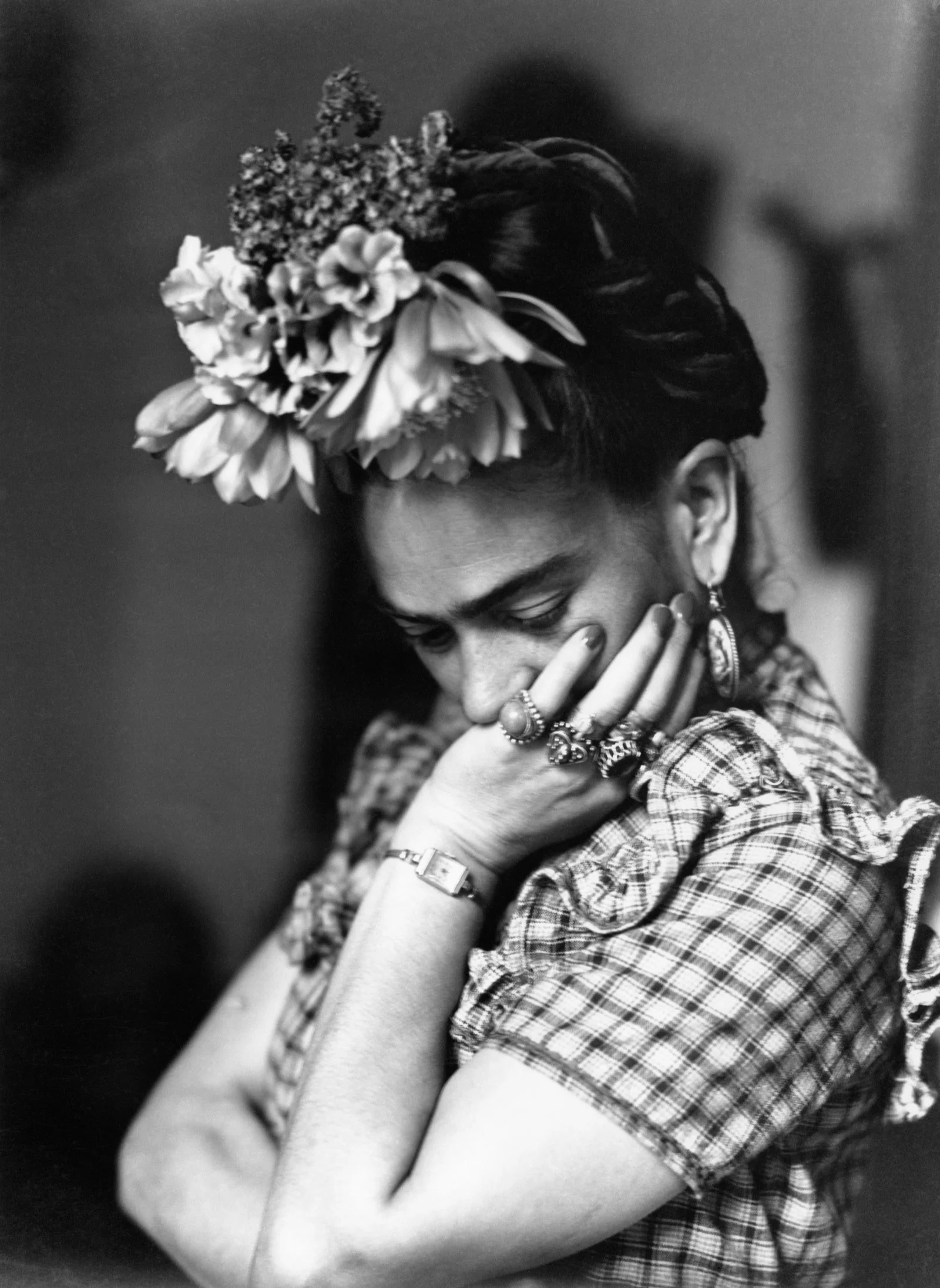

READ ABOUT FRIDA KAHLO, one of the most famous Fallingwater guests — and one of the most scandalous as well!

The narrow passageways on the second and third floors of Fallingwater are, again, designed to create a sense of compression. This helps make the terraces feel even more spacious and inviting when you step outside. With nearly equal square footage inside and out, the spatial quality of the terraces make it obvious that the outdoors are the home’s raison d’être.

The Kaufmanns were initially hesitant when Wright insisted on building the house over the waterfall. They had often visited the site to sunbathe, party and picnic with their friends, and they weren’t sure that they wanted to live so close to the rushing water. Wright was insistent that the house be built in this location. He told Kaufmann, “I want you to live with your waterfall, not just look at it.” He also wanted the sound of the waterfall to be the “music of the house,” and its sound can be heard in every room.

The built-in wardrobes are made of marine-grade plywood veneered with North Carolina black walnut. Note the sap line which runs vertically, referencing Wright's earth line. The wardrobe also include mildew resistant rattan shelving inside.

Liliane Kaufmann’s Bedroom

Although Edgar jr. desired to change the narrative surrounding his parents marriage, the room he renamed the Master bedroom was his mother Liliane’s. Separate rooms weren’t unusual for affluent couples in the 1920s and ’30s, as it was seen as a sign of luxury and privacy.

All of the woodwork at Fallingwater use marine-grade plywood, which was chosen because it’s resistant to warping in humid environments. The plywood was veneered with North Carolina black walnut, and was cut and milled by the Gillen Company in Milwaukee, the successor to the defunct Matthews Brothers Company, which Wright had used for his Prairie style houses.

This was done so that the sap line of the walnut tree would run horizontally, referencing Wright’s earth line. The only exception is the doors, where the sap line runs vertically to balance things visually.

The room has a collection of impressive artworks, including Fumeur, a Picasso aquatint, a Tiffany lotus lamp on the desk and Horikiri No Hanashobu (Iris Garden at Horikiri), a Japanese woodblock print by Ando Hiroshige. Sheltered within the niche of Liliane’s fireplace is an Austro-Bohemian Madonna and Child carved around 1420 CE (her favorite piece of art in the home.)

The niche above Liliane’s fireplace was custom-built to fit her favorite work of art at Fallingwater, a 15th century Madonna and Child.

At Rod’s instruction, our group proceeded down the hall and into Edgar Sr.’s bedroom.

A bust of Edgar jr. by Harlem Renaissance sculptor Richmond Barthé and a Savoy vase designed by Alvar Aalto sit atop the desk in E.J.’s bedroom. The desk has a semicircular cutout that allows the window to open without hitting it.

E.J.’s Bedroom

Using Juniors naming system Edgar Sr.’s bedroom is sometimes referred to as E.J.’s dressing room or E.J.’s study. The built-in desk features a semi-circular cutout so the corner window can swing open unimpeded. A bust of Edgar jr. by Harlem Renaissance sculptor Richmond Barthé and a Savoy vase designed by Alvar Aalto in 1936 sit on top of the desk.

One of the most striking features which can be seen from Edgar Sr.’s bedroom is the light screen, which runs vertically through the all three levels of the house. When viewed from the exterior, the vertical shaft of glass serves to balance the structural stone masses and maintain the house’s transparency. Wright was attempting to destroy the box of the traditional American home. He was bucking the International Style of the Bauhaus School in Germany. The casement windows here open outward, allowing their corners to vanish.

A rustic limestone sculpture by self-taught Mexican artist Mardonio Magaña sits on E.J.’s terrace. The Kaufmanns fell in love with his work when they visited Frida Kahlo’s Casa Azul in Coyoacán, Mexico.

A pair of Japanese woodblock prints, including Kōzuke Sano funabashi no kozu (Old View of the Boat-Bridge at Sano) by Katsushika Hokusai, circa 1830, and Street Scene on the Giroza-Yedo by Ando Hiroshige are on display. Six prints in total were given as gifts by Wright to the Kaufmann family. The original mat of Street Scene on the Ginza-Yedo bears the inscription, “to Junior: at Taliesin, Aug. 14, 1951.”

Wright liked to work with odd numbers. To balance the room, there are three semicircular shelves next to the bed. These symbolically represent the three family members of Fallingwater: E.J., Liliane and Edgar jr.

The adobe-style steps leading from the terrace outside lead to Edgar jr.’s study and bedroom on the third floor.

The zigzag adobe-style steps leading from the terrace outside Edgar Sr.’s second-floor bedroom to Edgar jr.’s study and bedroom in the third-floor penthouse are more form than function. They likely saw very little, if any, foot traffic, and, incidentally, put unnecessary stress on the terrace below.

A collection of books and sculptural objects grace the shelves of Junior’s third floor study.

Junior’s Bedroom and Study

On the third floor was the lair of the Kaufmanns’ son, Edgar jr. It consists of a stairwell library, a small den used as a drafting studio, and bedroom. The den also features cornerless windows. Junior’s sleeping alcove is at the eastern end of the passage. He preferred to be woken up by the early morning sun that streamed in through the spot created by the design of the bridge over the driveway.

Jean Arp’s abstract white marble Méditerranée II and Lyonel Feininger’s watercolor and ink on paper Church on the Cliffs VII are on view in Edgar jr.’s study.

Junior’s room wasn’t large — but it had a great view of the sunrise.

We exited Junior’s bedroom via a set of stairs and met at the second floor bridge connecting Fallingwater’s main house to the guest house.

A 28-inch-tall stone statue of the Hindu goddess Parvati from India, circa 750 CE, rests atop a boulder at the end of the covered passageway, accompanied by a freshly cut bunch of rhododendron leaves.

Bridge to the Guest House

The so-called “bridge” to connect Fallingwater’s main house to the guest house is actually a covered hall about 17 feet long that dead-ends at a boulder was left intact at the end of the passageway. There are five skylights equipped with bulbs so they can double as nightlights.

We continued up a set of stairs and paused in front of the cast stone statue Serena, another work by Richmond Barthé. The subject is Rose McClendon, a leading African American Broadway actress of the 1920s and the co-founder of the Negro People’s Theatre in Harlem.

While designing Fallingwater, Wright insisted that no rocks or boulders were to be destroyed or moved.

The semicircular cascading concrete canopy resembles folded Japanese origami and extends from the cantilevered trellis of the guest house. The material defies logic and has an incredible lightness, supported only by slender steel posts. The flanges flare out on the way up, but seem to disappear on the way down: Painted Cherokee red, the posts start at almost 7 feet tall and continue to less than 4 feet.

A slatted wood partition wall was used to divide the room without building a wall.

Guest House Living Room

The Guest House at Fallingwater was completed in 1939 and offered additional space and privacy for guests. One of the first things you’ll notice is that the ceilings are noticeably higher than the main house. Or maybe the small, asymmetric fireplace is what catches your eye.

Landscape: Jalapa, Mexico, an 1877 painting by Jose Maria Velasco, hangs over the guesthouse bed.

Guest House Bedroom

Rod told us that Liliane actually favored the seclusion and cross ventilation from the clerestory in the north wall of the guest house to her bedroom in the main house in the heat of the summer.

Landscape: Jalapa, Mexico, an 1877 painting by Jose Maria Velasco, a mentor of Diego Rivera, hangs over the guesthouse bed. The Kaufmann family acquired the painting around 1937 for $500. It originally hung in Edgar Sr.’s apartment at the William Penn Hotel in Pittsburgh until 1954, when it was moved to its current location.

Fallingwater’s bathrooms feature cork walls and floors, a soft and durable material. The toilets are also low, inspired by Wright’s time in Japan.

Every piece in the Kaufmann family’s collection has a story to tell. There’s a chair in the corner of the guest house bedroom from the home of Irving Washington, author of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. The Barrel Chair at the desk is Wright’s adaptation from an earlier design for the Darwin Martin House in Buffalo, New York.

Doors lead out to the 30-foot-long, 6-foot-deep spring-fed swimming pool on the terrace of the guest house. This was the result of a compromise between the Kaufmanns, who viewed swimming and sunning as an indispensable part of their enjoyment at Bear Run, and Wright, who resisted the idea of an artificial pool so close to a natural source of water.

The swimming pool is spring-fed and located on the terrace of the guest house.

An incredible amount of labor went into the construction of Fallingwater. The main contractor responsible for the masonry work was Walter J. Hall, a self-taught stone mason from Northern Pennsylvania, whose earlier construction, Lynn Hall, a roadside inn outside of Port Allegheny, won him the role. Hall taught the unskilled laborers how to construct walls using Pottsville sandstone. Minimum wage at the time was 25 cents an hour! By the time the guest house was built, the stone masons had honed their skills to perfection.

Our guide Rod was a great storyteller and extremely knowledgeable about the design and construction of Fallingwater. One of the best parts of the In-Depth Guided Tour was that we were able to take pictures both inside and outside of the house. Other tour options don’t allow photography beyond the first floor, so be sure to choose the one that’s right for you.

Whether you love or hate Frank Lloyd Wright the man, there’s no denying that his buildings are impressive. Fallingwater was every bit as fascinating as the photos you see online, and it was a truly unforgettable experience. –Duke

A view of the West Terrace and Sung Dynasty Buddha head.

Fallingwater

1491 Mill Run Road

Mill Run, Pennsylvania 15464

USA