Explore the Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site in Hyde Park, New York, with its original furnishings and garden.

Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site

We call it the Hamptons for Brooklynites. The Hudson Valley is known for its charming small towns, cultural attractions, natural beauty — and close proximity to New York City. And since Wally and I were spending a long weekend with my parents in this part of New York state, I was eager to find something we’d all enjoy doing together.

Wally, Duke and Poppa hang out before their tour.

No trip with my parents is complete without touring at least one historic landmark, and the region has plenty to choose from. Unfortunately, Olana, the Persian-inspired house museum of Frederic Edwin Church — a major figure of the Hudson River School of American landscape painters — was temporarily closed in preparation for an upcoming exhibit, so we opted for the Gilded Age “country house” of another Frederick.

This particular Frederick was the third son of William Henry Vanderbilt and grandson of the self-made multimillionaire, Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt — the man who inspired the term “robber baron” and amassed the family fortune in shipping and railroads. To me, the Vanderbilt family is synonymous with extraordinary wealth, designer jeans and one silver fox, aka Anderson Cooper. So as a “Duke” myself, it seemed only fitting to visit one of Dutchess County’s most notable estates.

Mema and Poppa are always up for a good time.

The turn-of-the-century mansion turned national historic site is perched on a natural bluff high above the Hudson River on the outskirts of Hyde Park, New York, about six miles north of Poughkeepsie on Route 9, and is a short distance from Springwood, the birthplace and lifelong home of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the 32nd president of the United States.

The Pavilion, now used as the Visitor’s Center, was constructed in just 60 days.

The Pavilion

Our first stop after arriving was the Visitor’s Center, a Georgian Colonial structure with a captain’s walk and porticos supported by Doric columns. These columns are actually brick pillars concealed by a material called staff, a mixture of plaster, jute fibers and horsehair. Often described as “counterfeit marble,” staff is cast into molds to resemble carved marble. The same material used to cover the buildings of the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois.

Originally referred to as the Pavilion, it was built in just 66 working days after the Vanderbilts acquired the property in May 1895. It replaced the Langdon Carriage House and served as the living quarters for Frederick and Louise while they oversaw the construction of the main house.

To prevent scandals, single men visiting the property would stay in the Pavilion, while unattached women slept in the nearby mansion.

Inside, Wally and I purchased tickets for the guided tour which were $15 per person, though my dad used his U.S. National Parks annual pass for military veterans to get my mom and him in for free.

The interior is styled like a gentlemen’s sporting lodge, complete with a large central fireplace and walls displaying a collection of mounted trophy heads of animals. It should be noted that Frederick himself didn’t hunt and strictly prohibited hunting on the property.

The building later served as the guesthouse for male visitors — you couldn’t have single men and single women sleeping under the same roof, after all.

Before our tour of the historic home, we followed a path leading to the formal gardens. As we crossed the expansive, meticulously manicured lawn in front of the mansion, I noticed my father admiring its orderly nature and could imagine him daydreaming of riding his latest John Deere lawn mower over it.

The marble fountain, depicting a young boy stepping on the head of an unusual-looking dolphin, has been restored.

The Formal Gardens

The gardens and grounds reflect the passion for horticulture shared by the estate’s previous owners. In the early 1800s, Samuel Bard established gardens and a greenhouse filled with native and exotic plants. He imported trees, flowers, herbs and shrubs from across Europe and Asia. The lone ginkgo tree standing in the middle of the south lawn is believed to have been planted by him in 1799.

Dramatic pergolas form a grand entrance to the gardens.

Bard’s approach was influenced by the principles of picturesque landscape design, which he studied during his time in Edinburgh, Scotland. Incidentally, as a doctor, he also performed a life-saving operation on the newly inaugurated President George Washington in 1789, removing a large and painful tumor from his left thigh.

Each year, volunteers plant around 6,000 annuals in the formal gardens.

After Bard’s death, his son sold the estate to his father’s former business partner, David Hosack, also an accomplished physician and avid horticulturist. Hosack was a professor at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University and in 1804 tended to Alexander Hamilton’s fatal injuries after his duel with Aaron Burr.

This statue of an odalisque, or harem member, was sculpted by Antonio Galli in the mid-19th century. The pool was being repaired when we visited.

Driven by his passion for botany, Hosack established the first formal gardens on the estate and built greenhouses to shelter his exotic plants. He enlisted the expertise of Belgian-born landscape architect André Parmentier who gave the grounds a park-like atmosphere.

Roads, bridges and lawns were carefully designed to enhance the natural landscape, while large areas were deliberately left in their wild state. Today, much of Parmentier’s original design remains unchanged.

This saucy statue was known as “Barefoot Kate.”

The four of us entered the formal Italian-style gardens at the northwest corner, where Wally and I left my mom and dad to linger at a table outside the tool house with miscellaneous items available for anyone to take, using an honor system.

“Barefoot Kate” isn’t really barefoot!

We continued up the gravel path and through the upper terrace gardens, where volunteers from the Frederick William Vanderbilt Garden Association were tending to the annual plants. This nonprofit works closely with the National Park Service to restore the gardens to their 1930s appearance.

Ahead of us stretched a walkway lined with cherry trees, leading to a brick loggia and reflecting pool. A white marble statue of an odalisque known as “Barefoot Kate,” stood in the central niche, appearing to delicately test the waters with her toe. On closer inspection, you can see she’s actually wearing sandals and isn’t even barefoot. The reflecting pool was closed for maintenance during our visit, but the vignette was still striking. The path continued down a flight of steps to the rose garden with a pavilion overlooking Crum Elbow Creek.

For those who might be curious, crimson roses were Frederick’s favorite and were delivered to his bedroom each morning. Louise preferred yellow roses, which she insisted be placed on the Louis XVI-style table in the drawing room.

Louise particularly loved roses and had part of the garden devoted to them.

Wally is always willing to visit a garden.

Duke sittin’ pretty

Flowering trees with gorgeous shades of pink can be seen in the hills beyond the gardens.

After meandering through the sprawling gardens, we met up with my parents and returned to the Pavilion, where we joined the group of visitors who were waiting in anticipation of meeting our guide.

The Vanderbilt Mansion is a prime example of Beaux Arts architecture, a style characterized by its grandeur and classical elements, popular in the Gilded Age.

The Country House

Mark Twain first coined the term “The Gilded Age” when he published his satirical novel The Gilded Age: A Tale of Today in 1873. The term refers to the economic boom between the end of the Civil War in 1865 and the turn of the 20th century.

The Vanderbilts were certainly emblematic of the era’s excess and grandeur. Frederick and Louise had an impressive real estate portfolio, with residences in Manhattan; Bar Harbor, Maine; Newport, Rhode Island; and a Japanese-inspired retreat on Upper St. Regis Lake in the Adirondacks. Yet, they sought a country retreat in the bucolic Hudson Valley.

Frederick was a director of 22 railroads, including the New York Central Railroad, the Pittsburgh and Lake Erie Railroad, and the Chicago and North Western Railroad. Despite their substantial wealth, the old-money families of the area, such as the Livingstons and the Beekmans, whose wealth went back at least three generations, labeled Vanderbilts “nouveau riche” and found them to be distasteful and crass.

Most recently, the property they desired belonged to Dorothea Langdon, whose father, John Jacob Astor, purchased it for her and her husband, Walter, in 1840.

A gilt bronze Louis XVI-style revolving dial clock, featuring the Three Graces holding a globe, by Henry Dasson, sits atop a table with a rare deep purple porphyry stone top.

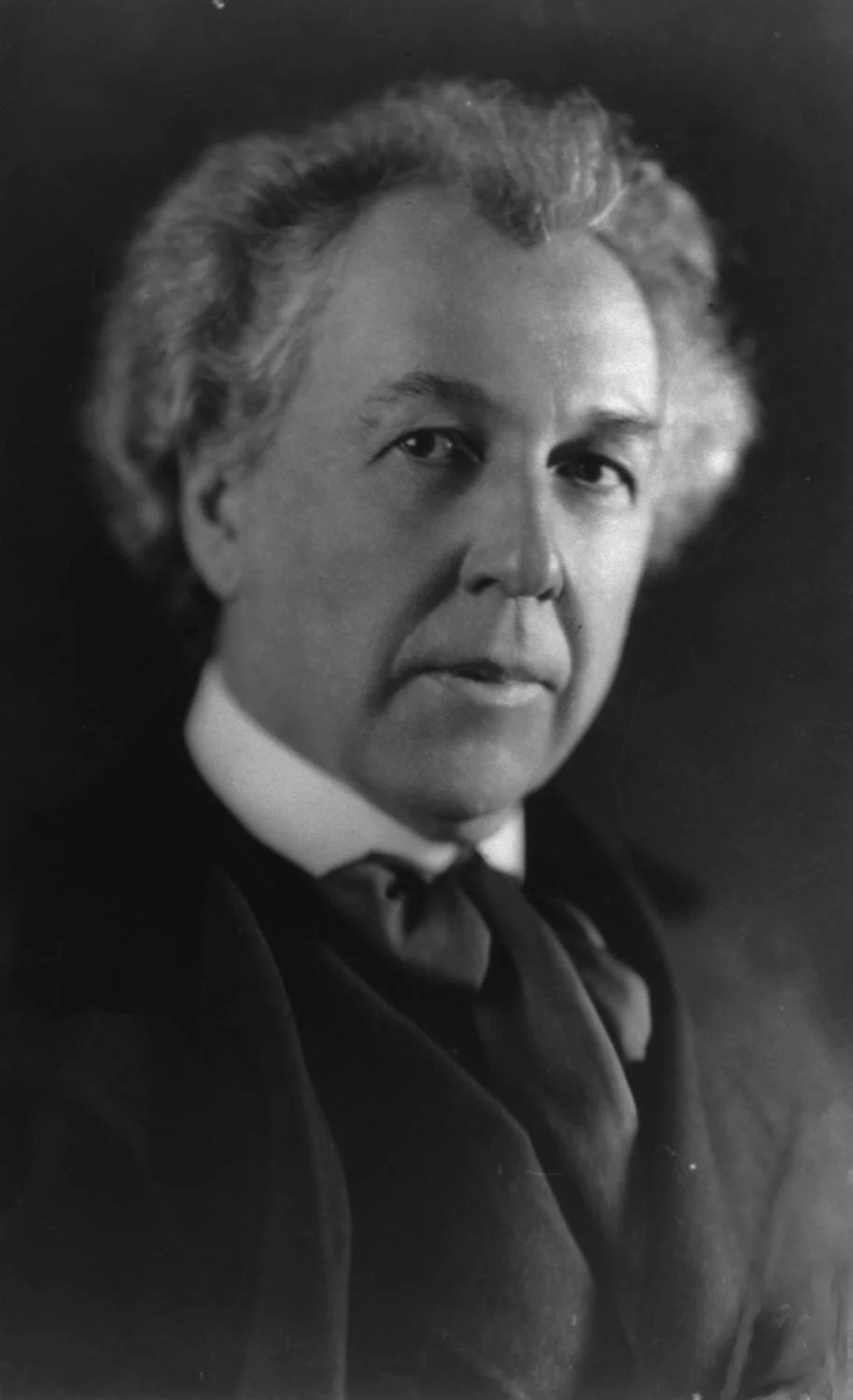

Frederick and Louise bought the property for under $25,000 and hired the prestigious architectural firm of McKim, Mead & White to replace the existing home with a new, larger version.

Frederick and Louise Vanderbilt. Are you surprised she was the outgoing one?

Charles McKim studied at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, and the home’s design reflects many elements of classic Beaux Arts style. Completed in 1898, its exterior is sheathed in Indiana limestone over a steel and concrete structure. Unlike its predecessor, the new house rose a full three stories.

Meanwhile, New York decorator Ogden Codman and architect Stanford White were tasked with furnishing the 54-room home with $2.25 million worth of museum-quality paintings and tapestries, and incorporating a range of European antiques and finely crafted period reproductions.

Despite its grandeur, the impressive 45,000-square-foot structure was considered “modest” in comparison to the opulent homes of Frederick’s siblings, such as George Washington Vanderbilt who erected the ostentatious Biltmore in Asheville, North Carolina.

Completed in 1899, the Hyde Park house featured all the latest innovations: electricity powered by a hydroelectric generator in Crum Elbow Creek — which according to our guide was a full decade before other homes in the town would experience this marvel themselves — central heating from coal-fired furnaces, and indoor plumbing. In 1936 the Otis Elevator Company electrified the existing hand-powered elevator.

The cost to complete the Vanderbilt Mansion was $660,000, which, adjusted for inflation, is roughly equivalent to $48.65 million today, excluding the furnishings.

A tapestry hanging in the Vanderbilt Mansion, Hector Bids Farewell, from the 17th century, shows the Greek hero of the Trojan War in Renaissance style dress.

While Frederick was described as quiet and introverted, Louise (who went by Lulu) was social and philanthropic and loved to entertain. She frequently hosted lavish parties, galas and balls at the Hyde Park estate, including an annual strawberry and ice cream festival for the community. She would also ride through town on a horse-drawn carriage during Christmastime and deliver presents to the children of Hyde Park.

And while they entertained friends now and then, for the most part, it was just the two of them — along with loads of servants — about 60 to be exact. Of these, 17 were employed in the house, two in the Pavilion, and 44 on the grounds and farm. Thirteen men cared for the gardens and lawns alone. When guests stayed in the Pavilion, additional cooks and maids were hired from the town of Hyde Park.

The front doors open to the reception hall, where you could sit on the sofa and admire the topless busts that support the mantel over the fireplace.

The Reception Hall

The main floor of the Vanderbilt Mansion was primarily used for entertaining. The first room we entered was the spacious reception hall, designed in an elliptical shape, lending it a sophisticated feel, similar to the Federal-style Oval Office in the White House. The octagonal opening in the ceiling enhances this geometric design, allowing natural light to flood the hall from the skylight above.

The great hall is furnished with a pair of matching tufted sofas, Italian throne chairs, and a mantelpiece bought from Raoul Heilbronner, a German-born art and antiques dealer in Paris. A 16th century tapestry bearing the Medici family crest hangs above it, suggesting that the family’s lineage dated back to the Italian Renaissance.

When Wally expressed surprise that there were a pair of topless caryatids supporting the mantle, our guide replied that the Victorians didn’t mind nudity — as long as it was done in a classical style.

Guests would meet in the home’s foyer before sitting down for a seven-course dinner in the dining room, a different wine being served with each course. The men and women would then split off to two separate parlors — women to talk about fashion and the like; men to discuss business. They would then convene in the drawing room before heading off to bed at midnight.

A collection of beer steins and a mounted elk's head adorn Frederick Vanderbilt’s cozy den.

The Study and Den

The first room to the left of the reception hall is Frederick’s study, mahogany-paneled with vaulted ceilings, a built-in desk and intricately carved wood panels. These architectural elements feature whimsical scenes of animals and cherubs, and were salvaged from a European château before being shipped to Hyde Park.

Unusual for the time, the study has its own bathroom — so Frederick could go about his business without the staff knowing.

The attached den has a bookcase holding about 400 volumes, mostly fiction and travel, along with Frederick’s textbooks from Yale.

Louise disliked the ceiling mural in her sitting room of Aurora and Tithonus by American painter Edward Emerson Simmons, so much she had it painted over. It was restored in 1962.

The Gold Room

Louise’s reception room was a feminine counterpoint to Frederick’s masculine study and was used for serving tea, sherry before dinner and gossip conversation. The coved and gilded plaster ceiling includes a mural by American impressionist painter Edward Simmons titled Aurora and Tithonus and was inspired by the mythological paintings of René-Antoine Houasse at Versailles. Apparently Louise hated it and had it painted over in 1906. Thankfully it was uncovered and restored by the National Park Service in 1962.

You can imagine the games of whist that were once played at these small tables in the drawing room.

The Drawing Room

To the left is the south foyer, which leads to the drawing room. This room features a pair of marble fireplaces and walnut paneling, and is furnished with a blend of antique Renaissance pieces and Louis XV-style seating.

The drawing room, designed in the French Renaissance style, was often the center of social activity, where guests would gather for conversation, music and games.

After dinner, the ladies would retreat to the drawing room, where a demitasse of coffee and liqueurs were served. Meanwhile, the men lingered in the dining room for another 30 minutes before joining the women for an evening of cards — often bridge — charades or dancing.

The dining room could seat 18 elite guests.

The Dining Room

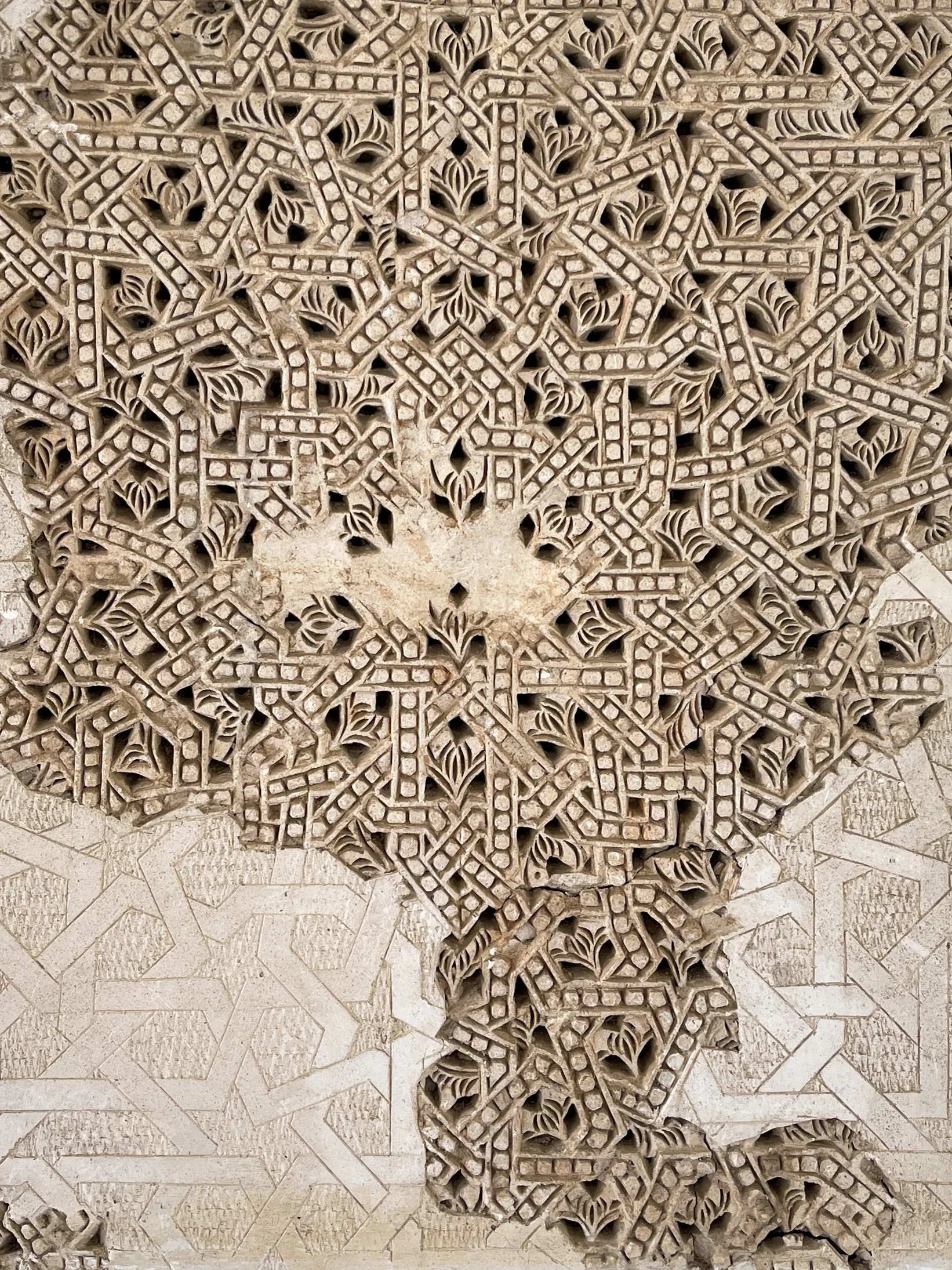

The dining room mirrors the scale and size of the drawing room. It includes a table that can be extended to seat 18 guests. Beneath it lies an Isfahan Persian rug, one of the largest in the world, measuring 20 by 40 feet and believed to be over 300 years old.

Like other rooms in the home, the furniture is a reproduction of the Louis XV period.

The central mural in the dining room, painted by Edward Emerson Simmons

The coffered and gilded ceiling was salvaged from an Italian palazzo, and installed to fit the space. The central mural was painted by Edward Emerson Simmons, a prominent member of Stanford White’s circle of artist friends.

The blue and white Ming Dynasty vessel at the base of the grand staircase is estimated to be over 500 years old. When the Vanderbilts lived here, it was used as a planter for a towering 20-foot palm tree.

The Grand Staircase

Roll out the red carpet: The grand staircase, with its sweeping wrought iron balustrade, has 10 steps leading up to a landing along the west wall, followed by another 10 steps to an east-facing landing, then 10 more steps heading west to a third landing, and finally nine steps east to reach the second floor.

The second floor is equally as impressive as the first. The elliptical central gallery is surrounded by a cast-stone balustrade and bedrooms, ranging from modest guest quarters to opulent his-and-hers rooms modeled after the Petit Trianon at Versailles.

This marble sculpture depicts the infant Hercules strangling one of the snakes sent by the goddess Hera to kill him in his cradle.

Niches hold marble sculptures of Eros and Psyche, along with Persephone, Greek goddess of spring and queen of the underworld.

Seven years later, the Vanderbilts enlisted New York architect Whitney Warren to redesign certain elements of the house. Warren removed the coved skylight (technically a laylight) atop the second story and replaced it with a flat frosted glass laylight. The wood balustrade around the opening on the second floor was removed to make way for a cast-stone balustrade and a deep plaster cove, embellished with lattice-work panels and oval medallions with female figures, was added to the ceiling of the second floor, beneath the new laylight.

Louise Vanderbilt’s bedroom and boudoir were designed after Marie Antoinette’s private rooms at Versailles.

One of the guest rooms at the Vanderbilt Mansion

Up on the third floor, of the 19 rooms, 11 belonged to female servants. Each morning floors were cleaned, silverware polished, porches swept, and 50 to 60 bouquets of fresh flowers were arranged throughout the home. The generosity of the Vanderbilts extended in many directions and was often expressed in donations of flowers to local churches and hospitals.

Compare this simple setup for the servants with the lavish decadence upstairs.

The Servants’ Hall

In an affluent household like this, servants were expected to be as invisible as possible, working behind the scenes to keep everything running smoothly. The staff usually arrived a day before Frederick and Louise to prepare the house. They had their own set of stairs and living spaces and were the first to rise and the last to retire for the night.

For the final part of the tour, our guide led us to the less grand service staircase, where we followed him down to the servants’ quarters. This was a simple and functional space with long corridors running north and south.

Directly beneath the dining room was the kitchen, where meals were prepared. Food was then sent up to the butler’s pantry on the first floor via a large dumbwaiter before being served in the dining room.

The kitchen downstairs

The basement also housed the unfussy servants’ lounge, which served as both a dining and sitting room where the staff could spend their leisure time.

Accommodations on this floor were for the male servants and included single rooms for the three butlers, a room for visiting valets, and quarters for the day and night men.

Additionally, the basement contained four storage rooms, two laundry rooms, an ironing room, a wine cellar and an ice room.

The laylight acts as a focal point of the Vanderbilt Mansion.

From Private Estate to Public Heritage: The Journey of the Vanderbilt Mansion

Everything in the house remained as it was when Frederick passed away on June 29, 1938, at the age of 82. Following his death, the first detailed archival records of the interiors were created. The P.J. Curry Company conducted a thorough inventory of the mansion’s contents, while Rodney McKay Morgan photographed many of the rooms for real estate purposes. The New York Times published photographs of the public rooms in 1940, and an album of snapshots, assembled by Fred and James Traudt that same year, is preserved in the home’s archives.

Since the couple had no children, the mansion was bequeathed to Frederick’s niece, Margaret Louise Van Alen. There was just one catch: She had no intention of living there and tried to sell the estate for $350,000, even reducing the price to $250,000. However, with World War II looming, and a country still recovering from the Great Depression, no one was really in the market for a mansion in Upstate New York.

Fortunately, President Roosevelt persuaded Van Alen to donate 211 acres, along with the mansion and its contents, to the National Park Service. The estate was preserved for the nation, renamed the Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site, and in 1940 opened to the public. According to the local Eagle News, 1,338 visitors toured the home within the first 10 days of its opening.

Fireplaces were a sign of wealth during the Gilded Age — so they were included, even when there was a central heating system installed as well.

The Lowdown

The Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site grounds are open to the public every day of the year, from sunrise to sunset. Tickets and visitor information are available in the Visitor Center, located in the building near the parking lot.

Admission is $15 per person and children 15 and under are free. The tour is free if you have the National Parks annual pass.

The hour-long tour was an enjoyable experience and gave us a glimpse into the lives of Frederick and Louise and their mansion. The visit takes you through the first and second floors, as well as the service basement. –Duke

At 45,000 square feet, the Vanderbilts’ holiday home featured 21 fireplaces, 14 bathrooms and 25 bedrooms.

Vanderbilt Mansion National Historic Site

119 Vanderbilt Park Road

Hyde Park, New York 12538