Housed in an 1818 Regency-style mansion, the Telfair Academy is the oldest art museum in the South. A can’t-miss stop in Savannah for art lovers, history buffs and fans of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil.

The Telfair Academy sits on the east side of Telfair Square, and is a short walk from West Broughton Street.

There’s just something about Savannah, Georgia: the moss-draped live oaks, the historic squares, and the beautiful architecture always draw us back. It’s a living, breathing city that honors its past while still looking toward the future.

Wally and I had visited Savannah many times before — wandering through the artsy, emerging Starland District, strolling up and down Broughton, and popping into the SCAD gift shop more than once. This time though, we decided to visit the Telfair Museums, which included the Telfair Academy and the Owens-Thomas House & Slave Quarters.

When we arrived at the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences, we were greeted by the towering sculptures of Phidias, Michelangelo, Raphael, Rembrandt, and Rubens. Hewn from limestone by Austrian sculptor Viktor Tilgner, each figure stands seven feet, six inches tall. Their commanding presence at the entrance to the stately edifice set the perfect tone for what awaited us inside.

We ascended the steps of the central porch and purchased our tickets at the museum gift shop, which included admission to all three museums: the Telfair Academy, the Jepson Center & Telfair Children’s Art Museum , and the Owens-Thomas House.

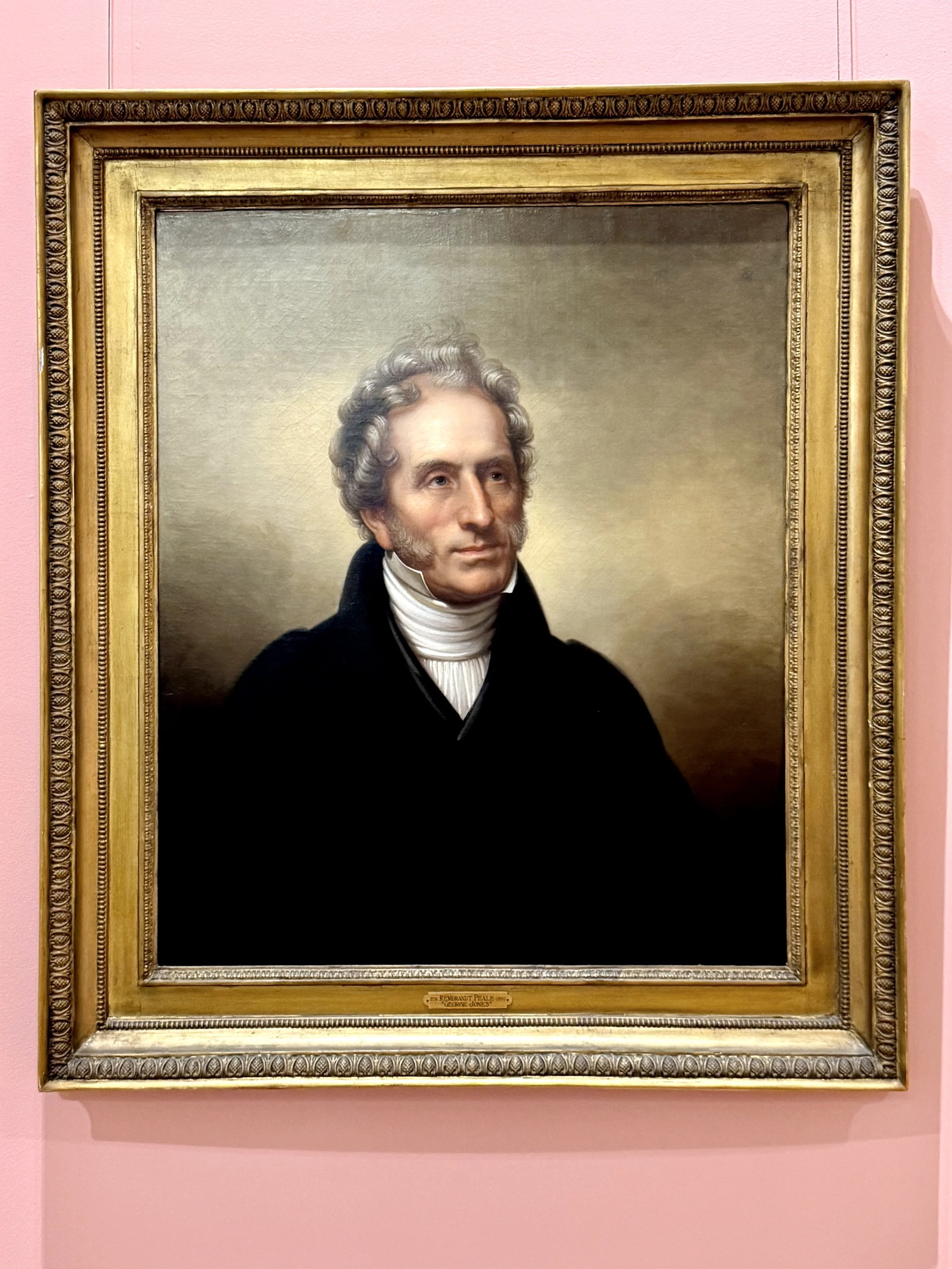

Portrait of Dr. George Jones by Rembrandt Peale, 1834

The History of the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences

The story of the South’s oldest public art museum begins with the death of Mary Telfair, the last surviving member of one of Savannah’s most prominent antebellum families. When she passed away on June 2, 1875, at the age of 84, she entrusted her Regency-style residence and its contents, along with a generous portion of her personal fortune, to the Georgia Historical Society. Her will stipulated that the home be converted into an institution dedicated to introducing art and culture to the public.

Fun fact: Mary Telfair’s bequest establishing the Telfair Academy preceded the idea for New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art by just one month, which was conceived by a group of men in Paris on July 4, 1866.

But instead of opening its doors, the house stood silent, caught in legal limbo for nearly a decade. Distant relatives challenged her will, alleging that she was not of sound mind. The dispute dragged on until it reached the U.S. Supreme Court, which ultimately upheld her wishes in Jones v. Habersham in 1883.

With the legal hurdles cleared, the Society’s board appointed the academically trained Carl Ludwig Brandt as the museum’s first director. A German-born painter who had crossed the Atlantic in 1852, Brandt was a trusted friend of Mary’s younger sister, Margaret Telfair Hodgson. In 1874, she commissioned him to paint a portrait of her late husband, William Brown Hodgson. That painting was unveiled at the 1876 dedication ceremony for Hodgson Hall, which Margaret had built in her husband’s memory to house the Society’s collections and library.

Perhaps it was this connection that convinced the board, and Brandt found himself tasked with the daunting job of converting the home into a cultural institution. He was given $20,000 (about $640,000 today) and passage across the Atlantic to procure works that would shape the museum’s permanent collection: engravings, oil paintings, full-scale plaster replicas of classical statuary, and casts of the Parthenon frieze and east pediment.

When Brandt returned, the board brought on architect Detlef Lienau to enlarge and adapt the home for its new purpose. Lienau removed the original staircase, raised the roofline, expanded the skylight, and effectively doubled the building’s size. Where the garden and former slave quarters once stood, he added a sculpture gallery at street level, topped by a rotunda to showcase the works Brandt had acquired in Europe.

On May 3, 1886, the former family residence officially reopened as the Telfair Academy of Arts and Sciences, marking a bold new chapter in Southern cultural history as the first museum in the United States to be founded by a woman.

Entrance Hall and Octagon Reception Room

The entrance hall of the Academy bears little resemblance to the original house. Lienau replaced the pine floors with marble and widened the passage to allow guests to move freely through what had once been a private residence. Today, the central corridor displays a range of works — from Harriet Hyatt Mayor’s 1915 bronze sculpture Art and Science to notable examples of 20th century American and French Impressionism and beyond.

Three Shack Landscape by Hughie Lee-Smith, 1947

Hughie Lee-Smith’s haunting surrealistic painting Three Shack Landscape depicts three weathered shacks — one dark brown, one red and one green — standing along a desolate, rocky shoreline beneath heavy blue and gray clouds. A burst of light cuts through, illuminating the dunes and stones around them, while in the foreground a lone pole with a twisted wire juts toward the sky, heightening the sense of isolation.

Lee-Smith was born in Eustis, Florida in 1915 and spent part of his youth in Atlanta before moving to Ohio, where he graduated from the Cleveland School of Art in 1938. After a brief stint in the Navy stationed on the Great Lakes Naval Training Center during World War II, he briefly taught art in South Carolina before settling in Detroit, where economic opportunities for African Americans were more abundant.

Lee-Smith moved to New York City in 1958, where he taught at the Art Students League. In 1967, he reached a milestone as the second Black artist to be elected to full membership in the National Academy of Design.

Le port de la Rochelle by Gaston Balande, 1949

French impressionist painter Gaston Balande’s Le port de la Rochelle captures a lively view of the harbor in La Rochelle, a historic seaport on France’s Atlantic coast. Painted around 1949, the piece reflects the influence of Paul Cézanne, particularly in his exploration of color, line, and form. Rather than relying on traditional perspective and chiaroscuro, light and shade techniques that defined Western art since the Renaissance, Balande used these elements to create depth and solidity.

Marketing by Robert Gwathmey, 1943

Robert Gwathmey was an American social realist painter known for his depictions of rural life in the American South, particularly the plight of African American sharecroppers. Born in Richmond, Virginia, in 1903, Gwathmey was deeply influenced by his experiences and observations of the South. In 1944, he spent time working alongside sharecroppers in Rocky Mount, North Carolina, to better understand their lives and challenges.

Like his contemporaries Jacob Lawrence and Ben Shahn, Gwathmey developed an abstracted figurative style. He utilized bold geometric shapes, flat planes of vibrant color, and minimal shading to convey his social commentary. This approach emphasized form and composition over naturalistic detail, giving his works a powerful and visually striking impact.

Jerry by Emma Cheves Wilkins, 1944

Octagon Reception Room

At the front of the Academy is the Octagon Reception Room. Once a traditional period room, it’s been reimagined to host the exhibition One Museum, Many Facades: Telfair Through the Ages. The walls still feature a rare, surviving example of early 19th century trompe-l'œil wood graining, a highly realistic, illusionistic painting technique that was popular when the mansion was built in 1818.

The room’s sparse décor makes the portrait of Jerry Dickerson above the fireplace mantle all the more special. Savannah artist Emma Cheves Wilkins painted it around 1942, shortly before Dickerson’s retirement after more than 25 years as a janitor at the Academy. This work captures him in his recognizable work attire: a collared shirt, tie, pin, apron and feather duster in hand. He lived in the basement offices, the former slave quarters and carriage house for the mansion.

After leaving the Octagon Reception Room, we passed the former Dining Room, which was undergoing restoration. Continuing down the hall, we came upon a set of staircases with ornate iron railings.

The view of the Sculpture Gallery from the top of the stairs reveals a subtle distinction in the flooring. The lighter-colored area on the marble floor marks the spot once occupied by a fountain installed in 1966 and removed in 1973.

The Sculpture Gallery

One set of stairs leads to the upper level, while the other descends into the Sculpture Gallery. We took the latter, and the moment we entered, my eyes were drawn to the dramatic plaster cast of Laocoön and His Sons — a copy of the famous Hellenistic masterpiece, which dominates the center of the gallery. Discovered in Rome in 1506 and now housed in the Vatican Museums, the sculpture depicts the Trojan priest Laocoön and his sons, Antiphantes and Thymbraeus, locked in a desperate struggle against deadly sea serpents.

When it first opened, the gallery displayed more than 70 plaster cast reproductions of classical sculptures, including the colossal Toro Farnese, which depicts the myth of Dirce, a cruel queen who was tied to a wild bull and dragged to her death by Amphion and Zethus for their mistreatment of their mother, Antiope.

There’s an unverified rumor that sometime in the 1970s, an Academy curator hosted a “sledgehammer party,” where guests were invited to destroy several of the institution’s large plaster casts. While it makes for a colorful story, there’s no proof to support it.

What almost certainly did happen is less dramatic: artistic tastes changed, and as the museum acquired more original works, the collection was gradually reduced, and in some cases destroyed, due to the high cost of maintaining them.

Pudicita, 1st century BCE (cast made before 1893)

Many of the works now displayed on the walls of the Sculpture Gallery were acquired through the efforts of Julius Garibaldi “Gari” Melchers, an American artist who served as the Academy’s fine arts advisor after Brandt. During his tenure, he acquired more than 70 works for the permanent collection, including many of the museum’s most treasured American Impressionist and Ashcan School paintings.

Stuyvesant Square in Winter, by Ernest Lawson, 1907

Brooklyn Bridge in Winter by Childe Hassam, 1904

After returning from Paris in 1889, American Impressionist painter Childe Hassam frequently turned his attention to New York City as a subject of his art. The city’s dynamic urban life provided ample inspiration for his work. In Brooklyn Bridge in Winter, Hassam employs pastel colors, a high vantage point, and broken brushstrokes — formal elements characteristic of Impressionism. This style, which he adopted during his time studying in Paris, emphasizes capturing the fleeting effects of light and atmosphere. Like the French Impressionists, Hassam was committed to portraying contemporary subjects drawn from daily life, and New York’s vibrant streets offered him endless material.

Vespers by Gari Melchers, 1892

Vespers contains all the hallmarks of Melchers’s early work: rural Dutch subject matter, a vibrant and colorful palette, and a keen interest in decorative pattern and texture. In this painting Melchers portrays Dutch villagers as hardworking, strong, and devout, tapping into a nostalgic yearning for traditional rural life during a time of rapid industrialization. The painting was originally owned by Walther Rathenau, an industrialist, writer and politician from Berlin who helped found the German Democratic Party.

Landscape grouping, with Shaghead by George Wesley Bellows and By the River by István Boznay, 1913

Lingering Snows by Willard Leroy Metcalf, 1924

In this panoramic view of mountains and a stream, Willard Leroy Metcalf captures the serene beauty of a New England spring. The painting showcases his signature Impressionist style, characterized by subtle harmonies of green and purple tones that evoke the gentle light of the season. This relatively large canvas was likely painted on site in Woodstock, Vermont, on the Ottauquechee River. Metcalf employs quick, textured brushstrokes, allowing the canvas to show through, to define the trees and left shore. Thicker paint applied with a palette knife in a blend of salmon and lime represents the sky, while soft, lightly mottled colors depict the river, the right shore, and the deep blue mountain shadow. Most striking is the irregular patch of snow resting in the upper right mountain dale, its whiteness matched only by the reflected white clouds in the river.

The Rotunda Gallery

We made our way back up the stairs and into the Rotunda Gallery: a breathtaking, spacious two-story room designed by Brandt and Lienau to emulate the grandeur of a 19th century European salon. Artworks in this style are hung close together on the walls, as opposed to being spaced out individually.

Grouping featuring works by Adolf Lüben, Robert Seldon Duncanson, George Majewicz and Guido Von Maffei

Look up, and you’ll see four paintings by Brandt positioned at the cardinal points of the gallery. Each work depicts a master of one of the four primary art forms, according to his view: Apelles for painting (west), Iktinos for architecture (north), Praxiteles for sculpture (east), and Albrecht Dürer for printmaking (south). The inclusion of three Ancient Greek artists reflects the late 19th century reverence for classical art and culture.

The Black Prince at Crécy by Julian Russell Story, 1888

Brandt purchased the impressive The Black Prince at Crécy from the artist Julian Story in 1889. Brandt acquired the painting with his own funds and donated it to the museum upon his death. The dramatic work portrays the aftermath of the Battle of Crécy during the Hundred Years’ War, and contrasts the historic figure of the Black Prince (the Prince of Wales) with the lifeless body of the fallen King John of Bohemia, highlighting the clash of heroism and tragedy on the battlefield.

La Parabola by Cesare Laurenti, 1895

Cesare Laurenti was born near Ferrara, Italy, but spent most of his life in Venice — the setting of La Parabola. In Laurenti’s day, German artists nicknamed the work Lebensbrücke, or Bridge of Life.

In a letter to Brandt, Laurenti explained that the painting was meant to reflect the course of human life, “the race toward pleasure, until clouds of weighty thoughts and sorrow come to disturb the serenity of the young soul.”

The first part of the scene is a lively celebration: two young men invite a group of young women to join in songs and laughter. At a doorway, a suitor representing Love kisses a girl’s cheek as she steps inside.

But the mood soon darkens. The same girl, now pensive, appears behind a window, her youth already fading. The scene then shifts to the entrance of a church, where “poor suffering souls seek relief.” Here, Laurenti wrote, “one can see the man, who, clad in priestly garments, represents Faith.”

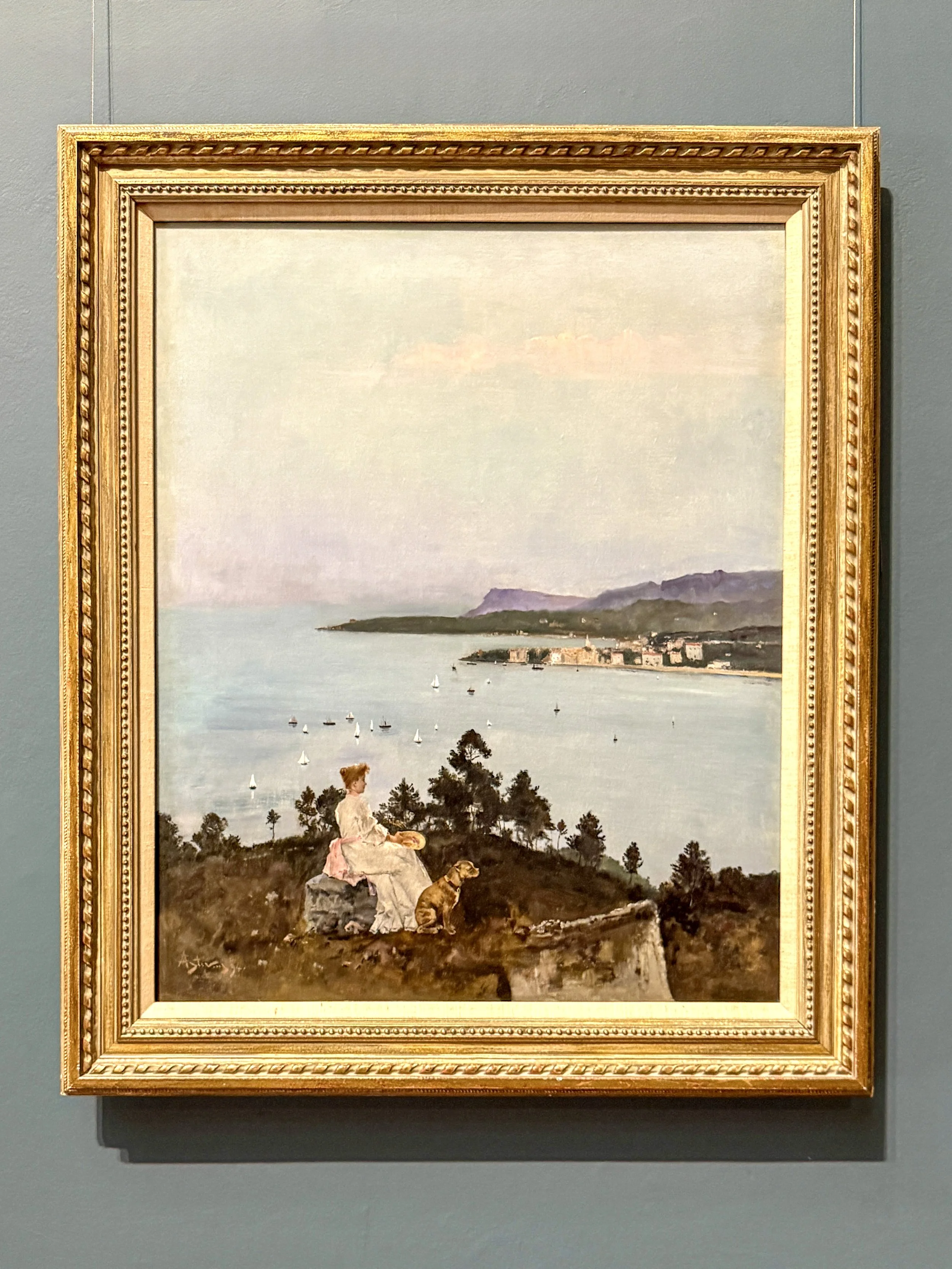

Jour de régates, Menton (Regatta Day, Menton) by Alfred E. Stevens, 1894

A view of the upper gallery, with a plaster casting of part of the frieze from the Parthenon in Athens, Greece

Second Floor Galleries

Upstairs, the rooms that once served as the Telfair family’s bedrooms were converted into galleries and feature works from the Academy’s permanent collections as well as temporary exhibitions. To make space for hanging art, original features like windows and fireplaces were covered up, leaving wide, uninterrupted walls for display.

The first two galleries held the ongoing exhibit Craft Along the Coast and included works from Telfair’s permanent collection that date from the 18th to the late 20th centuries. The first gallery presents examples of woodworking, ceramics and painting, while the second focuses on Savannah’s silversmithing traditions. Both galleries tell stories of markets and craft legacies, helping to draw lines of continuity through a dynamic history.

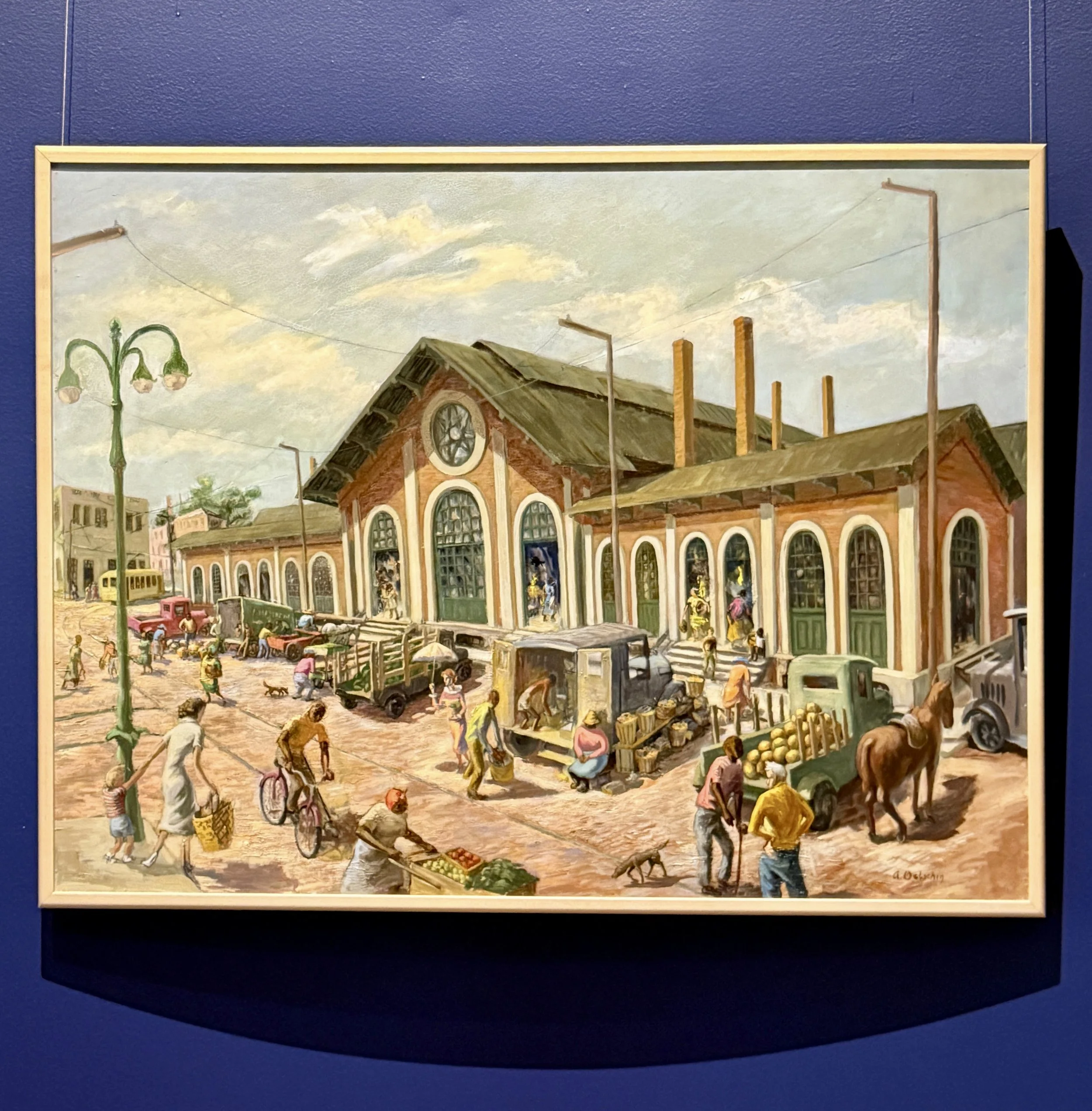

Old City Market by Augusta Denk Oelschig, 1950

Savannah native Augusta Denk Oelschig painted Old City Market, a lively portrayal of the City Market building that occupied Ellis Square from about 1872 to 1953. In the scene, the market pulses with life: Shoppers, vendors, produce stands and even animals are in motion across the square.

When the building was razed in 1954, the loss galvanized the community, and helped spark the creation of the Historic Savannah Foundation the next year, which continues to protect and preserve the city’s historic architecture.

In 1947, during a trip to Mexico, Oelschig met muralists Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco, whose work left a lasting impression on her. Inspired by the political and social themes in their art, she returned to Savannah with plans for a mural depicting the history of Georgia. Intended for the Savannah High School, her drafts included imagery of Ku Klux Klan members whipping African Americans and a reference to a politician later associated with the the Klan. Unsurprisingly, the school’s conservative officials rejected the proposal.

Savannah by Andrée Ruellan, 1942

In Savannah, Andrée Ruellan captures the view of the river seen between buildings and down a cobblestone ramp that leads to the wharves. The painting’s small figures (including a man with a cane and a vendor with children) evoke the quiet, everyday life of the waterfront rather than a bustling port.

Savannah’s riverfront historically relied on ramps (Barnard, Bull, Abercorn, Lincoln, etc.) down to River Street and its wharves, which is exactly the kind of setting Ruellan sketched. The waterfront was also a center for local craft traditions; Savannah has a documented history of woodcarving and walking-stick makers.

The iconic Bird Girl. Her outstretched arms don’t actually symbolize the weighing of good and evil — the shallow bowls in her upturned hands were intended to hold water and birdseed.

The Bird Girl of Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil Fame

I was especially intrigued by the gallery featuring Before Midnight: Bonaventure and the Bird Girl. It showcases artwork from Bonaventure Cemetery, including the famous statue.

Created in 1936 by Sylvia Shaw Judson, a sculptor from Lake Forest, Illinois, Bird Girl was first exhibited in 1938 at the Art Institute of Chicago under the title Girl With Bowls. Judson originally cast six versions, one in lead and five in bronze, but later stated that only four bronze casts were ever made.

One of the original bronzes was purchased by Savannah native Lucy Boyd Trosdal and installed in her family’s plot in Bonaventure Cemetery, where it was affectionately nicknamed “Little Wendy.”

For decades, the statue remained largely unnoticed — until photographer Jack Leigh captured its haunting image at dusk for the cover of John Berendt’s bestselling nonfiction novel Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, thrusting “Little Wendy” and the city into the national spotlight. Concerned about the crowds it began to attract, Trosdal removed the statue from the cemetery and loaned it to the Academy, ensuring it would be protected for future generations.

Fun fact: Jim Williams, the central figure in Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil, wasn’t just a successful antiques dealer and historic preservationist — he also served as president of the Telfair Academy.

An iron gate fragment from Bonaventure Cemetery hangs on the wall.

Bonaventure by Louis Bouché, 1969

Bonaventure Cemetery by Henry Clernewerck, 1860

Plaster bust of the Academy’s first director, Carl Brandt, by John Walz, 1891

Stay Awhile: Interiors in Art

The last gallery featured a selection of paintings from the Academy’s permanent collection that focused on interior settings.

Rather than emphasizing a specific narrative, the labels beside each painting encouraged visitors to form their own interpretations of the works.

The Lacemakers by Walter MacEwen, 1900

In The Lacemakers, three seated Dutch women are engaged in tatting the edges of a large piece of white fabric. Behind them, a man stands by a window, smoking a pipe and staring at the woman on the left, who seems lost in thought. The palette is dominated by muted, silvery tones, enlivened by the bright red bodices of two of the women and the tiny potted flowers on the windowsills.

A native of Chicago, Walter MacEwen had originally planned to pursue a career in business, but an unexpected event changed the course of his life.

When a destitute painter asked MacEwen for a small loan, the artist left his paint and brushes as collateral. He never returned to collect them, and MacEwen began to experiment with the abandoned materials.

By 1877 he had departed for Europe, where he studied under Frank Duveneck at the Royal Academy in Munich, and later at the Académie Julian in Paris. By the mid-1880s, MacEwen had established studios in Paris and Holland spending sixty years in Europe before returning to the United States in 1939.

Café Fortune Teller by Mary Hoover Aiken, 1933

The style of Café Fortune Teller evokes elements of American scene painting, characterized by its focus on everyday life and its narrative quality. The work was completed on the island of Ibiza prior to the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War and depicts the artist reading her own fortune amidst the bustle of a café. In 1936, Mary Hoover met the Savannah-born poet Conrad Aiken, whom she married in 1937. Her later works included portraits of famed author T.S. Eliot and British painter Edward Burra, and she also had solo exhibitions at the Telfair in 1964 and 1975.

Wally and I visited on a weekday and spent about 90 minutes exploring the galleries and browsing the gift shop. Admission for adults was $30, valid for seven days from the date of purchase and offers access to all three museums. –Duke

Telfair Academy Visitor Information

Hours of Operation

Open Wednesday through Monday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.

Closed on Tuesdays

Admission Fees

Tickets grant unlimited access to all three Telfair museums (Telfair Academy, Jepson Center and Owens-Thomas House) for seven days from the date of purchase.

Adult: $30

Senior (65+): $27

Active military (with ID): $27

Student (ages 13 to 25, with ID): $20

Child (ages 6 to 12): $10

Child (5 and under): Free

Accessibility and Visitor Services

Wheelchair accessible: Yes. Entrance is on the south side facing President Street (with nearby accessible parking and elevator access).

Sketching: Allowed with pencil only; sketchbooks no larger than 8½ by 11 inches. No easels or sitting on the floor.

Photography: Non-flash photography is permitted for personal use unless otherwise posted. Tripods, selfie sticks, lights and other gear are prohibited.

Checkroom policy: Bags larger than 11 by 14 inches must be checked. Laptops and luggage are not accepted.

Strollers: Restricted in the historic Telfair Academy and Owens-Thomas House but welcome at the Jepson Center.

Why You Should Visit the Telfair Academy

Historical significance: Established in 1886, it’s one of the first public art museums in the U.S. and the first in the South.

Architectural beauty: A Regency-style mansion designed by English architect William Jay (built 1818 to 1820).

Collections and highlights: 19th and 20th century American and European art, restored period rooms, decorative arts and the famed Bird Girl statue.

Telfair Academy

121 Barnard Street

Savannah, Georgia 31401

USA

![Nackte Schiffer (Fischer) und Knaben am grünen Gestade (Naked Boatmen [Fishermen] and Boys on the Green Shore by Ludwig von Hofmann](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c13cc00442627a08632989/bf99309e-65ac-4776-a40b-93c658b11225/Naked+Boatmen+%5BFishermen%5D+and+Boys+on+the+Green+Shore+by+Ludwig+von+Hofmann.jpg)

![Untitled (kuchi-e [frontispiece] with artist’s seal Shisen) by Tomioka Eisen](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/56c13cc00442627a08632989/acfc8a3b-574b-4822-a787-aca814e59f46/Untitled+%28kuchi-e+frontispiece+by+Tomioka+Eisen.jpg)