The all-too-short life of the Boy King, Tutankhamun, who gained fame when Howard Carter discovered his tomb — one of the only ones in the Valley of the Kings that wasn’t plundered by grave robbers.

This is what King Tut’s tomb looked like when Howard Carter discovered it in 1922

Ever since I was a young boy, I’d yearned to visit Egypt. I was fascinated by King Tutankhamun and the discovery of his mostly intact tomb, with its wealth of magnificent, well-preserved artifacts.

For starters, the Boy King’s legacy is fascinating. Filled with political corruption, incest, religious upheaval and a possible murder, his history is just as epic as the eight seasons of George R.R. Martin’s Game of Thrones — and, much like the addictive HBO adaptation, it all collapsed in the end.

Born in 1341 BCE, his given name was Tutankhaten, Beloved of the Aten, the solar disc of the sun worshipped at Amarna, the capital city established by his father, Akhenaten, the revolutionary heretic king who embraced Aten as the sole supreme being for Egyptians to worship.

A sphinx bearing the head of Tutankhamun at the Luxor Museum

The Boy King

Tut was nicknamed the Boy King because he ascended the throne around the age of 8 or 9. Some historians have suggested his vizier, Ay, was the real power behind the throne, citing that it was Ay’s decision to abandon the new capital city of Amarna and restore the authority of the priests and the polytheistic pantheon of Thebes. Whatever the case, when Tut died without an heir, Ay briefly became king.

Like other pharaohs, Tutankhamun took five royal names, and most of us know him by his fifth nomen, Tutankhamun, after he dropped the -aten suffix in favor of -amun, chief among the old gods. Ancient Egyptians, though, would have called him by his prenomen or throne name, Nebkheperure, which essentially meant Ra Is the Lord of Manifestations to honor a different sun god.

A goddess guards Tut’s canopic shrine

Incest Is Best?

Tutankhamun was married to his half-sister, Ankhesenamun. The practice of incest to keep the royal bloodline pure was common among the ruling class of Ancient Egypt. They regarded themselves as representatives of the divine on earth. Atum, the god of creation, produced his children Shu and Tefnut by his own hand (aka jerking off). His daughter Tefnut married her twin brother Shu, and voilà! Nut and Geb were added to the ever-expanding pantheon of incestuous liasons.

Tut and Ankesenamun had two stillborn daughters, likely casualties of genetic deficiencies from generations of inbreeding. Their tiny mummified fetuses were buried in Tutankhamun’s tomb. A DNA study revealed that one was 5 to 6 months old and the other 9 months old.

Because of his link to the scandalous Akhenaten, Tut’s reign was eventually struck from the record by his successors. Between the ever-shifting desert sands and the Ancient Egyptians attempt to remove all traces of the “Amarna heresy,” Tutankhamun was literally out of sight and out of mind. This in all likelihood helped to preserve his tomb.

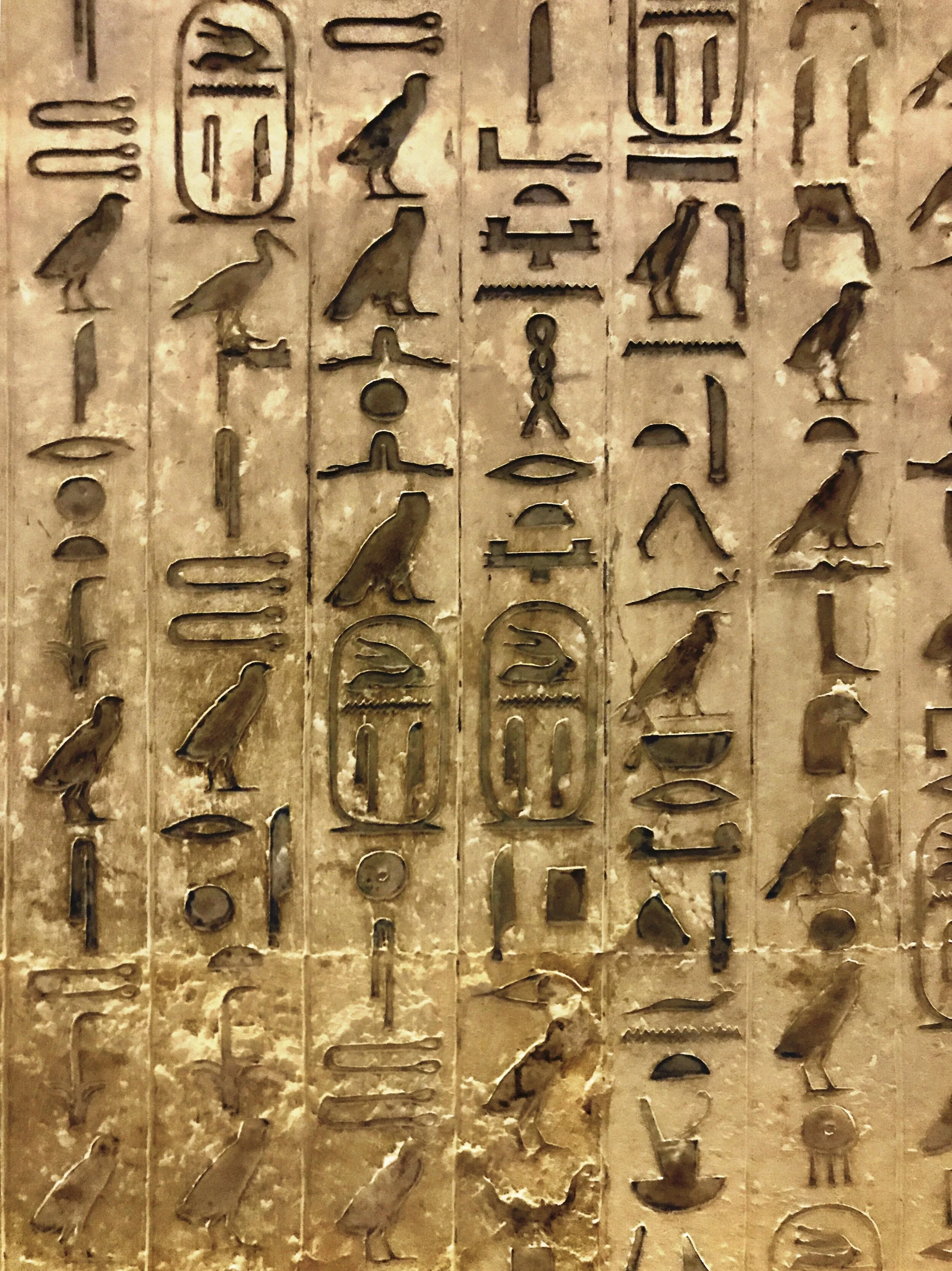

The Abydos Kings List

Tutankhamun, Akhenaten (aka Amenhotep IV), Ay, Hatshepsut and Meryneith were some of the rulers stricken from the official record.

Lord Carnarvon, his daughter Evelyn and Howard Carter

The Untouched Tomb

Unlike other royal tombs, which were looted in antiquity (often by the very laborers who built them), 5,000-some items were found inside King Tut’s tomb.

British archaeologist Howard Carter was no stranger to the Valley of the Kings and had been obsessively searching for the elusive burial site of Tutankhamun for years. In 1914, his financier George Herbert, the 5th Earl of Carnarvon, secured a license to excavate a parcel of land close to the tomb of Ramesses VI. Carter hired a crew of workers to help find the tomb, but was halted by World War I.

By 1922, Lord Carnarvon, frustrated with the lack of progress and financially spread thin, informed Carter that he would only extend funding for one more season unless Carter struck pay dirt. Like sand in an hourglass, time was running out, when, on November 4, while excavating the very last plot, the crews’ waterboy discovered a step that appeared to be part of a tomb. Carter immediately wired his employer, and the excited Lord Carnarvon arrived two and a half weeks later, with his daughter Lady Evelyn Herbert.

Carter made a tiny hole in the plaster-sealed entrance. By the light of a candle, he was stunned by what he saw and wrote in his diary:

Presently, as my eyes grew accustomed to the light, details of the room within emerged slowly from the mist, strange animals, statues and gold — everywhere the glint of gold. For the moment — an eternity it must have seemed to the others standing by — I was struck dumb with amazement, and when Lord Carnarvon, unable to stand the suspense any longer, inquired anxiously, “Can you see anything?” it was all I could do to get out the words, “Yes, wonderful things.”

Carter and an assistant unveiled the remains of Tutankhamum

Next came the laborious task of cataloging and removing each artifact from the tomb, beginning with the antechamber. Carter called upon the skilled archaeological photographer Harry Burton, who happened to be among the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Egyptian expedition team working at the nearby site of Deir el-Bahari. Burton captured the contents of the tomb as they were found. Then, a sketch and description were made on numbered cards before the object was carried out on wooden stretchers. Carter would eventually catalog thousands of artifacts from the tomb. The final contents were finally removed 11 years later, on November 10, 1933.

Did breaking this seal unleash a curse upon all present?!

The Curse of King Tut’s Tomb

Shortly after the burial chamber was opened, stories of the legendary mummy’s curse began surfacing. Rumors quickly spread that Carter had found a clay tablet over the tomb’s entrance that read, “Death shall come on swift wings to whoever toucheth the tomb of the Pharaoh.”

Near the end of February 1923, Carnarvon was bitten on the cheek by a mosquito. He reopened the bite while shaving, a seemingly innocuous event that would prove fatal. Carnarvon died in Cairo two weeks later from sepsis-abetted pneumonia.

Even the likes of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, who by this time had stopped writing his popular Sherlock Holmes mysteries in favor of spiritualist leanings, weighed in, declaring to the press that “an evil elemental may have caused Lord Carnavon’s fatal illness. One does not know what elementals existed in those days, nor what their form might be. The Egyptians knew a great deal more about these things than we do.”

Carter, however, seems to have escaped the mummy’s curse and lived on until 1939, when he died of lymphoma at the age of 64.

You’ll have to pay an extra $15 or so to see King Tut’s mummy and tomb

Visiting King Tut’s Tomb

While exploring the Valley of the Kings, Wally and I decided to pay the extra fee of 250 Egyptian pounds (about $15) to see KV62, the tomb of Tutankhamun. The site isn’t included with the three tombs that are part of the 200 L.E. fee to the royal necropolis. I imagine this cost is a measure put in place by the Department of Antiquities to limit the amount of visitors entering the tomb. Moisture from breath and perspiration increase humidity levels in the subterranean rock-cut chambers, which in turn damage the lime plaster wall paintings covering the walls.

The small tomb is less impressive than the other ones you’ll visit in the Valley of the Kings and lacks the elaborate linear design predominantly used by New Kingdom pharaohs — the sun god Ra would find himself challenged, having to follow some twists and turns as he makes his nightly descent at sunset.

Unlike other tombs, which are covered with paintings, only Tut’s burial chamber is decorated

Tut’s mummified remains lie on display in a climate-controlled glass box in the tomb’s antechamber. We were the only ones inside at the time and were followed around by a guard, probably to make sure we didn’t take pictures. I incorrectly assumed that my photography pass would be valid and that I could take non-flash pictures while inside. I learned that was not the case when I tried to take a shot of the Boy King’s remains. –Duke