Whether you need a break from exploring the temples of Luxor and Karnak to escape the heat or just want to take a virtual tour, the Luxor Museum is filled with amazing statues and reliefs of King Tut, Akhenaten and other famous pharaohs, as well as Egyptian gods including Amun, Sobek and Sekhmet.

Not too many travelers bother with the Luxor Museum — but that’s a mistake.

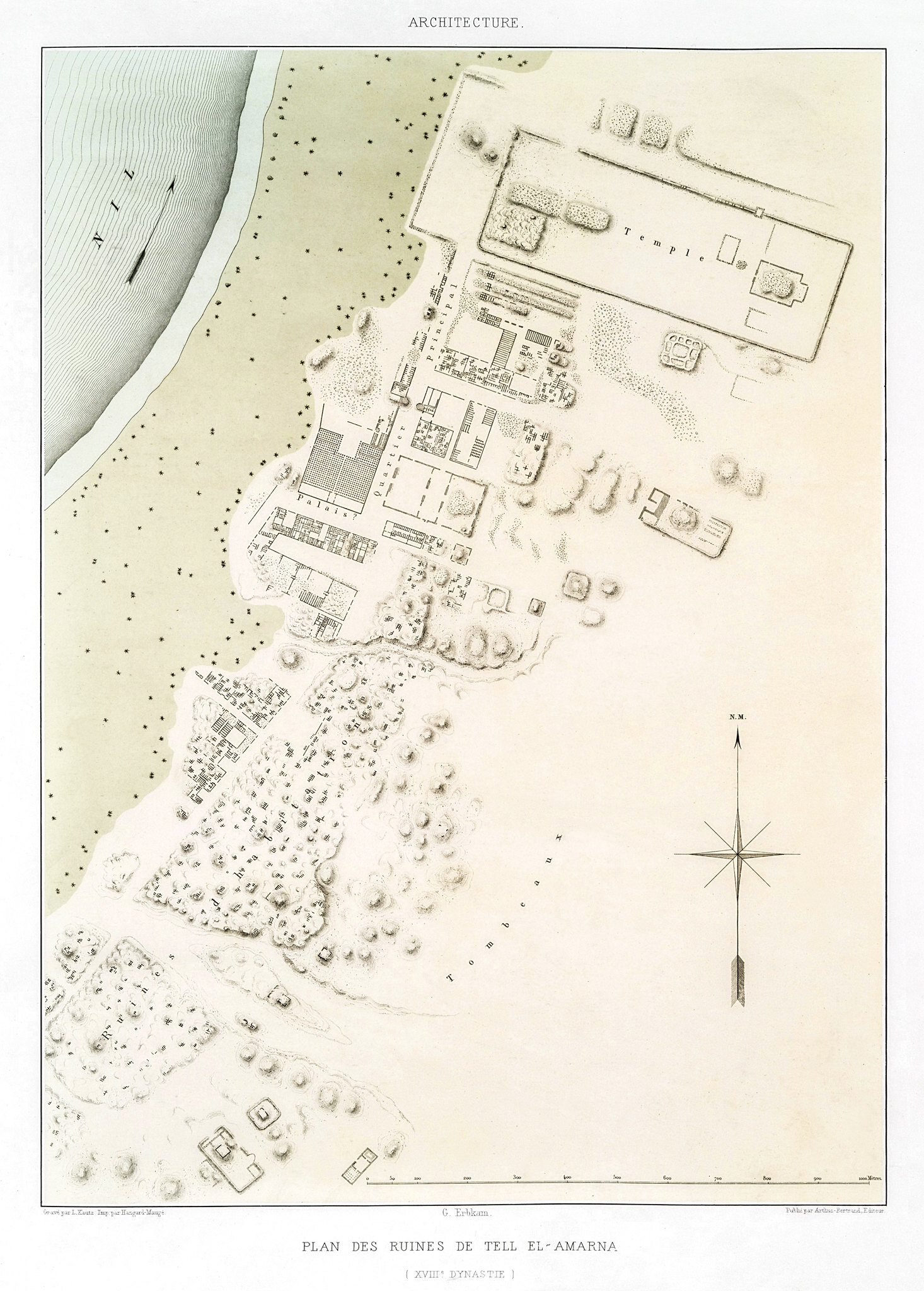

A processional route over a mile and a half long once connected the temples of Luxor and Karnak. There’s talk of renovating and reopening this roadway, and it would be an impressive sight, lined with noble sphinxes, with the glittering water of the River Nile twinkling off to one side. To be honest, though, I can’t imagine that long of a walk, with no shelter from the sun god Ra’s blazing heat.

After you’ve explored Luxor or Karnak Temples, though, you can escape the intense sun with a visit to the Luxor Museum. Even though it’s situated about a 20-minute walk from Luxor Temple, partway to Karnak, it seems as if not too many tourists add this to their itinerary.

When we suggested it to our guide, Mamduh, he looked a bit surprised, as if we might have been the first people he’s had make the request.

“If you want to see a lot of the statues that once filled the temples of Ancient Egypt, you’ll have to visit a museum.”

The interior is a cool, sleek white space with angles that give it a surprisingly modern feel. It’s not too large of a space, which means you can see the entire collection in an hour or so.

Guides aren’t allowed to lecture about the various exhibits. So Mamduh, who had been with us all week, educating us on Ancient Egyptian culture and archeology, from Aswan up to Luxor, had to shift his role. He was no longer our teacher; he became a friend exploring the museum with us. Judging from the sparkle in his eye and his childlike sense of wonder, he hadn’t spent much time in the museum and looked at this as an opportunity to increase his education.

The mummified remains of Ramesses I have a colorful past, including a stint at Ripley’s Believe It or Not! in Niagara Falls, Ontario. Unlike at the Egyptian Museum in Cairo, you can actually photograph this mummy.

Where Are the Statues of Ancient Egypt?

The temples of Ancient Egypt, once packed with statues, are now sadly bereft of these works of art. I often remarked to Duke how much I wished the niches, sanctuaries and pedestals were still home to the statues that once adorned them. If you want to see these statues, you’ll have to visit a museum — and the one in Luxor fittingly houses numerous carvings that were unearthed at the nearby temples of Karnak and Luxor.

Before we started wandering the museum, we stopped into an auditorium to watch a short documentary about Thebes (the ancient city where Luxor now stands). The fim had a grainy, bootlegged quality that revealed how woefully outdated it is. It reminded Duke and me of the film reels we used to watch in elementary school. To be honest, I don’t recall much about it. If time is limited, this is definitely something you could skip.

Here’s a brief tour of the Luxor Museum, showcasing some of our favorite artifacts.

Senusret I (circa 1971-1926 BCE)

Limestone

Part of the colossal pillar of Pharaoh Senusret I from the White Chapel at Karnak, the structure was built to commemorate the first anniversary of the Sed Festival, held during the 30th year of his reign. Senusret is depicted in the traditional form of the god of the afterlife, Osiris, with arms folded across his chest and holding an ankh, the symbol of life, in each hand.

Senusret III (1878-1840 BCE)

Quartz

This quartz head, found at Karnak, sporting the double crown and false beard, captures the humanity of the great Twelfth Dynasty ruler. His heavy-lidded eyes and supposed slight smile (I don’t really see it) represent a break in the sculptural tradition of Egypt’s Middle Kingdom.

Amenenhat III (1841-1792 BCE)

Black granite

Check out that look of disgust! Stern features like this were typical of the Middle Kingdom statuary.

Ramesses III (1550-1532 BCE)

Graywacke

This cult statue of Ramesses III, the last great warrior king of the New Kingdom, wears a short wig surmounted by the double crown. One part of the sculpture, which decorated the Precinct of Mut at Karnak, was discovered in the 1930s by the Oriental Institute of Chicago. The other was unearthed in 2002 by an expedition team from Johns Hopkins University.

Thutmose III (1490-1436 BCE)

Graywacke

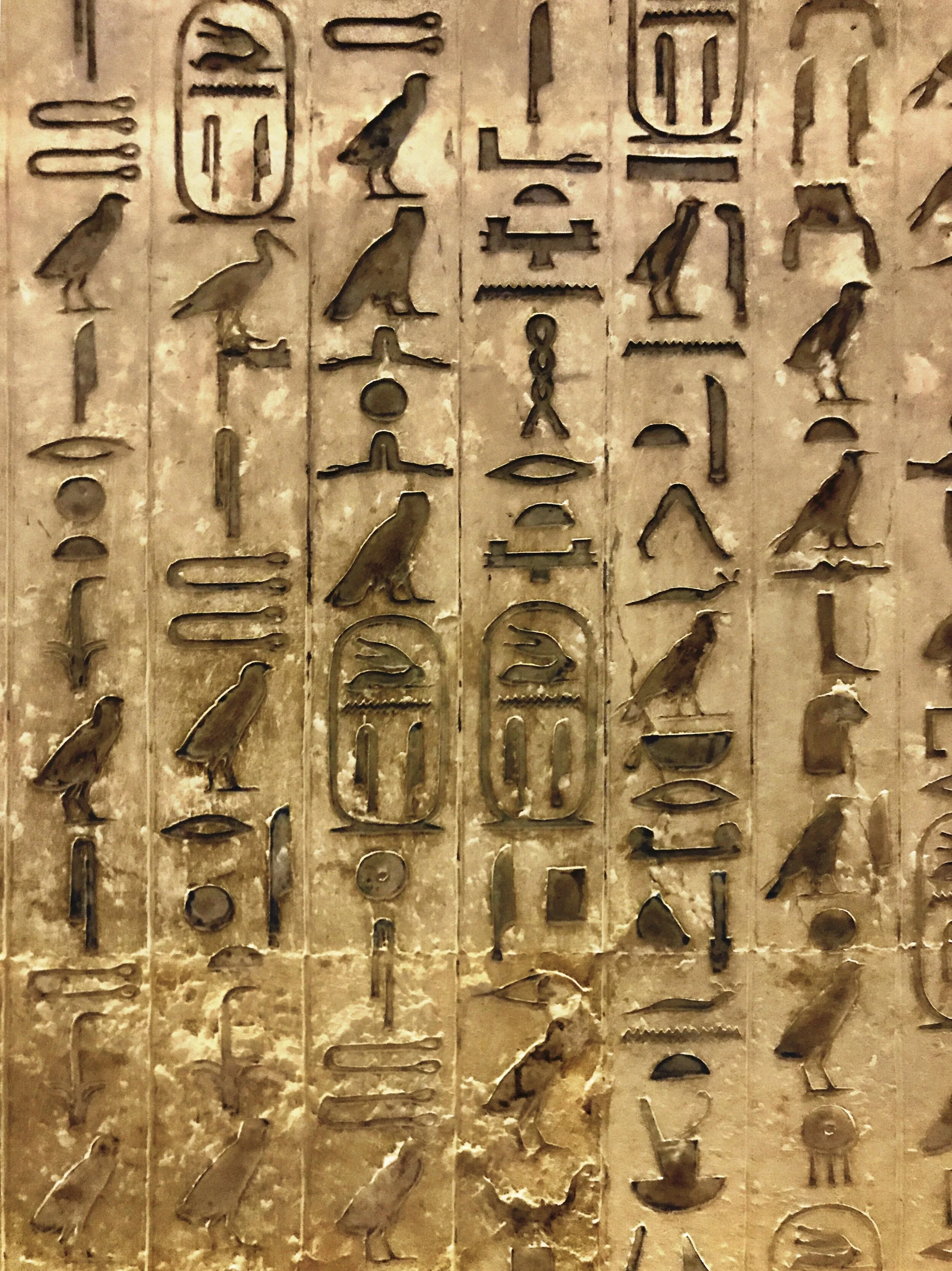

Shown eternally youthful, Thutmose III is wearing a belt with his cartouche, an oval carving with the pharaoh’s name in hieroglyphics.

Amun-Min relief (1490-1436 BCE)

Limestone

Look at those colors, still so bright after thousands of years! The chief deity Amun is merged with the fertility god Min. The relief, from Deir el-Bahari, was destroyed during the Amarna period and restored by a later pharaoh.

Unknown officer (1440-1400 BCE)

Sandstone

This uninscribed Eighteenth Dynasty painted statue depicts an officer wearing a shebyu collar. While these necklaces were often worn by New Kingdom pharaohs, they were also given as a reward for valor or distinguished service.

Amenhotep II relief (circa 1426-1400 BCE)

Red granite

Amenhotep II was particularly proud of his prowess as an athlete and warrior. He’s shown shooting arrows through a target. In the inscription, he boasts of being so much stronger than normal men that he uses copper for target practice rather than wood, through which his arrows pass like papyrus.

Sobek and Amenhotep III (circa 1386-1353 BCE)

Calcite, Egyptian alabaster

The crocodile-headed deity holds an ankh to bestow life to the youthful ruler. The statue was usurped by Ramesses II.

Iwnit (1405-1367 BCE)

Diorite, possibly

This statue of Iwnit, a minor goddess from the Amduat and consort to the god Montu, was created during the reign of Amenhotep III. With dimples at the corner of her mouth, which give the impression of a fleeting smile, some call this the Mona Lisa of Karnak.

Amenhotep III (circa 1386-1353 BCE)

Quartzite

This New Kingdom figure of Amenhotep III was originally adorned with gold that was removed in antiquity, leaving some rough spots visible where armlets once were.

Sekhmet

Gray granite

The war goddess Sekhmet personified the fierce protective aspects of women and was known as the Mistress of Dread (coolest nickname ever?). In the New Kingdom she belonged to a group of goddesses known as the Eye of Ra. Here she’s shown with a broken sun disk above her head.

Amenhotep, son of Hapu (1400 BCE)

Granite

This statue of a seated scribe with stylized fat folds represents Amenhotep, son of Hapu, an important official under Pharaoh Amenhotep III. A palette with two inkwells, one for red and one for black, hangs over his left shoulder. As overseer of all the king’s works, a post he reached later in life, he was responsible for many of Amenhotep’s ambitious building projects. Like Imhotep, he became deified after death.

Wall painting of Amenhotep III (circa 1386-1353 BCE)

Painted stucco

Sadly, all that’s left of this wall painting from the tomb of an official are fragments. The image shows Pharaoh Amenhotep III seated under a canopy, with his mother behind him and his enemies beneath him, a position of power. If you want to see what this would have looked like in full, the facsimile painted in 1914 by Egyptologist Nina de Garis Davies can be viewed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York City.

Amenhotep III (circa 1386-1353 BCE)

Granodiorite

This sculpture from north Karnak depicts the kneeling figure of Pharaoh Amenhotep III, a popular figure at the Luxor Museum. Holding a pair of flails, the king is kneeling during his coronation by the god Amun-Ra, whose now-missing hand would have originally rested upon Amenhotep’s crown.

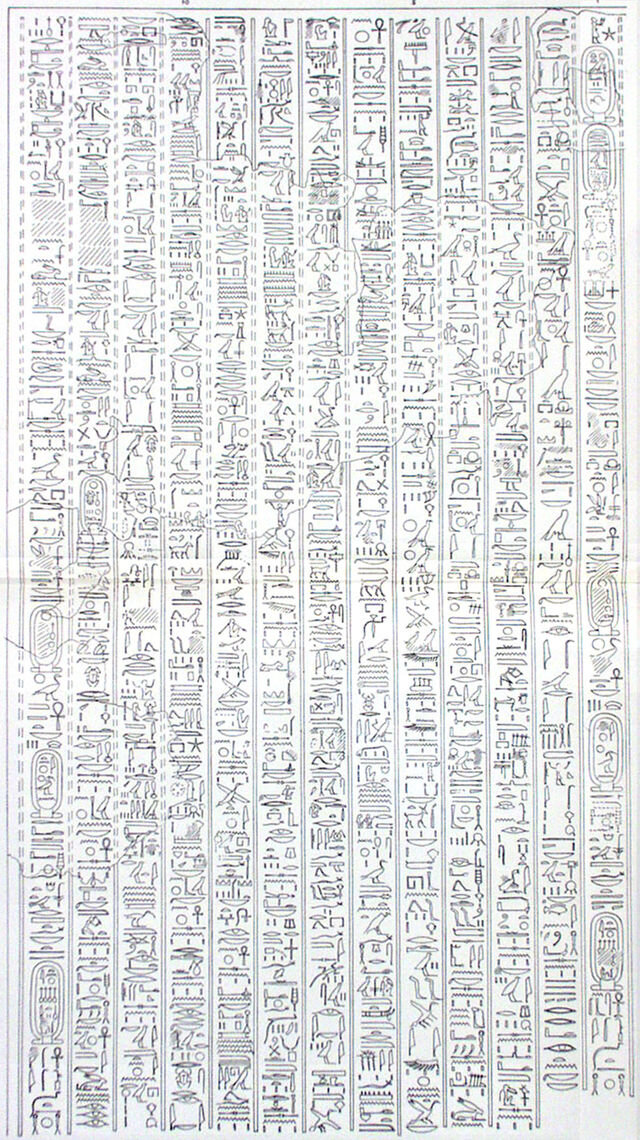

Temple wall of Amenhotep IV aka Akhenaten (circa 1380-1335 BCE)

Sandstone

This partially restored wall from a razed temple dates from the first five years of Amenhotep IV’s reign. The fragments, known as talatat, were used as filling material and removed from the interior of the ninth pylon at Karnak. This scene depicts the so-called Heretic King and his wife Queen Nefertiti worshipping the multi-armed Aten, with images of daily life associated with the temple storehouses, workshops and breweries.

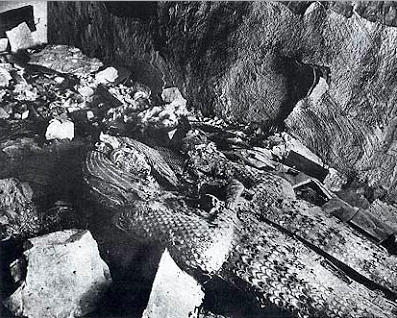

Akhenaten (circa 1380-1335 BCE)

Sandstone

These are the remains of a colossal statue in the easily identifiable Amarna style (which we both love) found east of the Amun-Ra temple precinct, in an open court dedicated to the solar god Aten, built by Akhenaten in the third year of his reign. The colossi were knocked down and left in situ during the reign of Horemheb. During an excavation in 1925, Henri Chevrier, chief inspector of antiquities at Karnak, uncovered 25 fragments.

Tutankhamun sphinx (1347-1336 BCE)

Calcite

The face of this sphinx from Karnak Temple appears to bear the features of King Tut — most noticeably in the eyes and chin. This likeness wears a nemes headdress and originally had human arms that held a vase.

Tutankhamun as Amun (1347-1336 BCE)

Limestone

Amun, the patron deity of Thebes, is depicted in the form of the legendary Boy King. Tutankhamun restored the cult of Amun (and the other gods) after the death of monotheistic, monomaniacal Akhenaten.

Atum and Horemheb (circa 1300-1292 BCE)

Diorite

The militaristic Pharaoh Horemheb kneels before the solar deity Atum, offering two nw jars. Atum is seated on a throne, holds an ankh and wears a long wig and a curved false beard, topped with the double crown of Egypt. Carved into the side of the throne is the sema tawny, lung and windpipe, symbolizing the union of the two lands (Lower and Upper Egypt). The well-preserved artwork was discovered in 1989, buried beneath the solar court of Amenhotep III at Luxor Temple.

Seti I (1323-1279 BCE)

Alabaster

Wally thinks the spot where his penis would be was a light switch. Seti I was a warrior king like his father Ramesses I before him. He was the husband of Queen Tuya and the father of Ramesses II also known as Ramesses the Great. A passionate builder, he’s responsible for the hypostyle hall at Karnak.

Nebre (circa 1292-1189 BCE)

Sandstone

This work was discovered at a fortress that protected the western border of Egypt from the Libyans. Nebre served as a commander under Ramesses II and held multiple titles, including troop commander, charioteer of the king, overseer of foreign lands and chief of the Medjay, an elite police force. He holds the staff of office, topped by the lion head of Sehkmet, goddess of war. –Wally