Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright collaborated on this sleek, minimal home that defied the ostentatiousness of the Gilded Age. Step back in time and tour this innovative but little-known architectural gem.

Imagine what people thought of a home like this — sleek, modern, horizontal — at a time when Victorians were all the rage. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

When dealing with such legendary icons of the architectural world as Louis Sullivan and Frank Lloyd Wright, it’s not surprising that towering egos and intense rivalry come into play. But with the iconic Charnley-Persky House in Chicago’s Gold Coast neighborhood, who actually deserves the accolades?

“Wright wrote that he had designed the Charnley-Persky House entirely on his own.

The claim couldn’t be refuted, as Sullivan had passed away, and the firm’s records had burned in a fire. ”

Helen Charnley

The Charnleys Want a “Country” Home

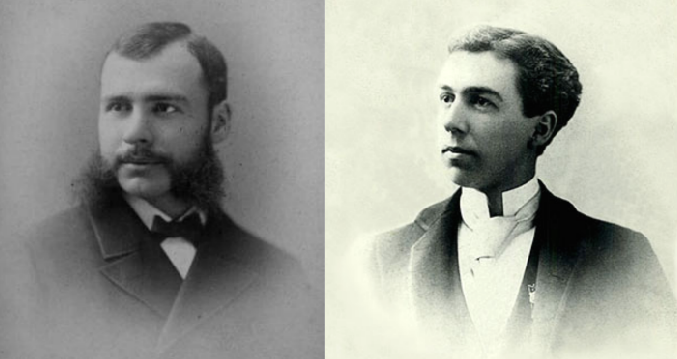

Let’s start at the beginning to try to unravel this mystery. In 1891, Sullivan, 34, and his then-23-year-old apprentice, Wright, teamed up to design a residential masterpiece on Astor Street for their wealthy clients, James and Helen Charnley.

The couple were members of the one-percenters of the Gilded Age. James was a banker who made his fortune in lumber, and Helen’s father was president of the Illinois Central Railroad.

At the time, Sullivan and his partner, Dankmar Adler, were basically the cool kids of the architecture world. They had designed the Auditorium Theater Building in 1889, which is still world-renowned for its acoustics. Business was good.

While many of Adler & Sullivan’s 180-some commissions were for commercial spaces, they also designed about 60 residences. Unfortunately, most of them are no longer standing. In fact, the Charnley-Persky House is the only residence designed by Sullivan that you can still tour today.

So how did the Charnleys manage to snag Sullivan as their architect? Well, it turns out that James’ brother, Albert, was an executive at the Illinois Central Railroad. As our guide, Jean, joked, “The rich like to hang out with other rich people.”

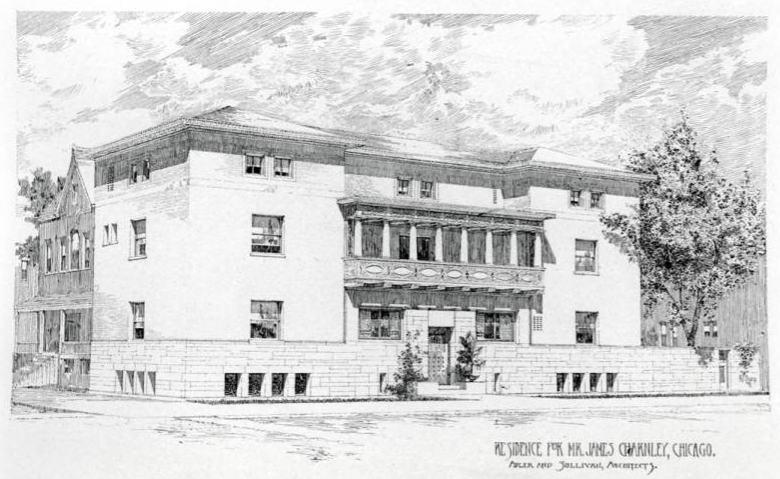

Adler & Sullivan’s architectural drawing of the James Charnley home

But why did the Charnleys choose this location? They were ahead of the curve. While the Gold Coast is now an affluent neighborhood, at the time it wasn’t exactly a hot spot. In fact, even though it’s not that far north of downtown, it was considered the countryside.

Three-quarters of a mile in one direction, you would reach the Chicago River. Go three-quarters of a mile in the other direction, and you’d find yourself in a notorious slum charmingly known as Little Hell. It was gnamed for the smell of sulfur from the coal gas furnaces that permeated the air. It was so dangerous that even the police wouldn’t go there, Jean told us. (What did that neighborhood eventually become? The infamous Cabrini Green housing project.)

So how did this land become prime real estate? Well, Potter Palmer, Chicago’s richest resident at the time, had a lot to do with it. He built his own home on the corner of Lake Shore Drive, spending a whopping $1 million back in 1882. The house was called “the Castle” for its size and design.

“Of course, it raised the value of all the land around it,” Jean said. “And so it started to get developed very quickly after that.”

You can see why the Palmer home was called the Castle. It helped make the Gold Coast a hot new housing market.

Sadly, no one could afford to keep up the Castle, and it was razed in 1950.

Before that, this area was owned by the archdiocese, with parts of it acting as a Catholic cemetery, and the only other building in sight was the archbishop’s residence.

The Charnleys’ first home in the undeveloped Gold Coast neighborhood of Chicago was a site of heartbreak. Note the Palmer Castle under construction in the background.

The Charnleys Join the Neighborhood

The Charnleys built their first home on Division and Lake Shore Drive, but lost their two young daughters (ages 4 and 6) to diphtheria shortly after moving in. The memories of that house weren’t happy, so they decided to have this one built instead. It was never intended to be a family home. They had larger homes in the suburbs of Lake Forest and Evanston, so this was simply their pied-à-terre in the city, Jean explained.

Even today, it stands out from its neighbors with its modern design, a product of Sullivan’s experimental phase.

After the Charnley’s departure, the house went through several owners, including the Waller family, who had a member living there until 1969. Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM) bought the house next for the headquarters of the Chicago Institute for Architecture and Urbanism and restored it.

“They didn’t stay here long. But fortunately, they had deep pockets,” Jean said. “So they were able to restore the structure to the way it was, which no private owner could do before them.”

Philanthropist Seymour Persky later bought the house and let the Society of Architectural Historians (SAH) move their headquarters there from Philadelphia. This allowed the house to continue to stand and be appreciated for its architectural significance. As a token of its gratitude, the society added Persky’s name to the home.

Bustling State Street in the 1890s, when Chicago was one of the fastest-growing cities in the world

Gilded Age Chicago

To put the time period into context, Chicago underwent exponential growth and development during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In 1880 the city’s population was 500,000; in 1890 it had doubled to 1 million; and in 1910 it had doubled yet again to 2.2 million.

“At that time, the turn of that century, it was the fastest-growing city in the world,” Jean said. “Of course, that’s a thing of the past now. But it was a very new, vibrant, lively, energetic city with lots of money, lots of wealth, lots of disease, lots of extremes.”

Rudyard Kipling visited Chicago around this time and declared, “I urgently desire never to see it again. It is inhabited by savages.” Rude.

In 1889, the Chicago Sanitary District was formed to reverse the flow of the Chicago River, which had been dumping waste into Lake Michigan and contaminating the city’s drinking water. A New York Times article from the time said that the water in the Chicago River “now resembles liquid.” (Sorry, St. Louis!)

As Jean pointed out, the tail end of the Gilded Age in Chicago was a time of juxtaposition, when typhoid epidemics and inaugural symphony concerts were happening simultaneously.

Start your tour of the Charnley-Persky House Museum where the servants used to spend most of their time, in the basement. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

The Basement/Visitors center of the Charnley-Persky House

Our tour of the Charnley-Persky House began in the basement, which is the visitors center. This floor was strictly for the servants’ use, so the family had no reason to come down here.

The basement contains a kitchen, boiler room, laundry room, bathroom, root cellar and butler’s pantry with a dumbwaiter.

The soapstone sink has a concrete basin. “I think the reason it’s still here is because it’s too heavy to move,” Jean speculated. “Some things are just too inconvenient to destroy.”

Overall, the house presented some design challenges, starting with its narrow footprint. It has 4,500 square feet spread across four floors — but it’s only 25 feet deep from one wall to the other. It’s essentially designed in the space of a row house, but with the entrance on the long side instead of the short side.

What’s impressive is how Sullivan and Wright got creative with elements of the home’s design. Originally, another house was planned to be built against the back wall, so there were no windows on that side. The architects added interior windows to bring light into the space. How sweet of them to consider the welfare of the servants.

The Charnleys were lucky (err, rich) enough to have hot water in the home. When it came to heating, Sullivan and Wright went against the norm by hanging the hot water radiator below the floor — and saved a lot of room in the dining room upstairs.

This genius feature hides the radiator and saves all that space from making the dining room above more cramped. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

There’s a door off to the side of the main room that leads to the coal cellar. It’s actually built under the sidewalk, and a manhole out front offered access for delivery men to shovel coal in.

Higher-end Roman bricks were used on the front of the home, with cheaper Chicago common bricks at the back. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

The Façade of the Charnley-Persky House

Most of the homes in the Gold Coast neighborhood are grandiose 19th century Victorian row houses with sharp vertical lines and elaborate ornamentation on their windows, doors, porches — basically everywhere. Many are made of rusticated brownstone and sport an asymmetrical design.

So one thing that sets the Charnley-Persky House apart is its horizontal layout.

“There’s nothing like it anywhere around here — even now,” Jean pointed out.

Chicago was a brick-making center in the 1890s, manufacturing about 600 million bricks a year. This house reflects that. On the back side, Chicago common brick was used. Uneven in color and crumbly, they were made from clay in the Chicago River. They were also much cheaper than other types of brick. However, the front and sides of the home feature more expensive Roman brick and natural limestone.

The front door of the house. You can see the importance of horizontal planes and symmetry in the home’s design. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

In the design, Sullivan exaggerated the horizontal planes. The natural limestone goes all the way across the front section and the side. There’s a balcony that spans the front. It has pillars, but they are short and squat. The Roman brick is narrow. And you can’t see the low-hipped roof at all.

The design is notable for its lack of ornamentation around the windows and doors. “Sullivan wanted the mass of the building itself to be present to us, and not to cover it up with all kinds of frills and doodads — that’s the architectural term,” Jean joked.

Also in stark contrast to its neighbors, the house is completely symmetrical, with the front door and balcony in the center and the same number of windows on each side.

The house is devoid of decoration, aside from the metalwork on the balcony, which features some of Sullivan’s recurring motifs. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

Looking at the design of the Charnley-Persky House, there are a few key motifs worth noting. One of these is the incised pattern on the balcony, which can be seen throughout the building, including the front door. Sullivan loved to incorporate organic shapes and patterns into his work, and he often referred to the pointed oval motif as a seed pod.

“He put them on every single thing he designed,” Jean said. “Everything, even down to the tombs in Graceland Cemetery.”

Sullivan was certainly ahead of his time with this house. He was so proud of it that he advertised it in architecture magazines in England, promoting it as the first American modern design.

Louis Sullivan, on the left, most likely designed the Charnley-Persky House — but that didn’t stop Wright, on the right, from taking credit later in life.

The Sullivan and Wright Controversy

Wright was working as a draftsman for Sullivan at the time the Charnley-Persky House was built. Evidence shows that Adler and Sullivan, well-established architects at the peak of their business, would design the entire plan of the house, including the decoration and wood choices. Then, Wright would fill in some of the details.

“So, while there are some unique elements that may be Wright’s additions, the overall design was likely a collaboration between the three architects,” Jean informed us.

But that’s not what Wright claimed. In his 1932 autobiography, Wright wrote that he had designed the house entirely on his own. And the claim couldn’t be refuted, as Sullivan had passed away in 1924, and the firm’s records had burned in a fire.

“Sullivan and Wright were very close, until they weren’t,” Jean said. “They both had very big egos.”

Wright left Adler & Sullivan in 1893. He claimed he was fired for moonlighting, building other houses on his own.

“But evidence suggests Sullivan didn’t care,” Jean went on. “I think Sullivan said, ‘You’re fired.’ And Wright said, ‘You can’t fire me — I quit.’ It was one of those situations. I think Wright had reached a point where he had the skills and the confidence to leave and go on his own.”

Jean added that Sullivan was an alcoholic and very difficult to get along with, while Wright was brilliant and visionary.

The narrow entrance hall at the home, where the fireplace takes center stage. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

Inside the Charnley-Persky House: The Foyer

Step inside, and the first thing you notice is the foyer fireplace, which boasts original mosaic designs that echo flickering flames. The flue is hidden underneath the stairs and goes up the back. The fireplace has no mantel, which allows for an unobstructed view and emphasizes those horizontal lines that are a hallmark of Sullivan’s style.

Sullivan incorporated elements of the Arts and Crafts movement, which highlighted craftsmanship and natural materials. The use of wood as the main decorative element and the incorporation of organic motifs, such as oak leaves and acorns, were typical of this style.

Wide, expensive white oak panels feature prominently. Remember, Charnley was in the lumber biz.

Those skylights illuminating the stairwell and landings is something you’d typically find in commercial buildings — not a family home. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

The design of the Charnley-Persky House reflects Sullivan’s experience with commercial buildings, as well as his innovative approach to residential design. The atrium and skylight, which were more commonly found in commercial buildings, allowed for natural light and air to flow through the home. This was a departure from the typical dark, closed-off interiors of Victorian homes.

To either side of the door are cozy alcoves. The Charnleys didn’t leave any letters, diaries or photos, so we have no idea how the family used these spaces. However, there’s only one sitting room, so it’s possible that these alcoves served as small reception areas for guests before entering the dining room.

No one’s quite sure what the Charnleys used the alcoves to either side of the front door for. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

According to the 1900 census, the Charnley family had two live-in Swedish servant girls. “You know,” Jean said. “You’re a servant girl until you’re at least 80.” The “girls” did the cooking, cleaning and everything else that needed to be done around the house.

The dining room at the Charnley-Persky House was much less elaborate than most in the Gilded Age. Photo by David Schalliol

The Dining Room

Wide, beaded paneling was all the rage back then. You could buy strips of beaded wood and simply glue them onto a surface. Sullivan kept the room plain and modern, aside from the fireplace. The richly carved mahogany mantle with a stylized four-point seed pod motif, surrounded by a vegetal pattern, is set above African rose marble tiles imported from England.

“I don’t know why they’re not from Chicago. We made everything else,” Jean mused. “But anyway, that’s where they’re from.”

The rose marble tiles of the fireplace in the dining room came from Britain, while pretty much everything else was locally sourced.

The buffet isn’t original, but the woodwork suggests that there was probably a built-in piece of furniture there at some point. So the folks at SOM custom-designed one to fit in. Look closely: Its design mimics that of the house exterior.

Unusual for the more-is-more Gilded Age, there are no parquet floors or ledges to be filled with statues, crystal and the like.

The Charnleys were quiet folk who didn’t entertain much. In addition to the deaths of their daughters, James was diagnosed with Bright’s disease in the mid-1890s. This chronic kidney inflammation had no treatment or cure — it was a one-way ticket to the grave. He survived only 10 years after his diagnosis.

Unfortunately, the Charnleys couldn’t catch a break. James’ brother and sister-in-law ran off with $100,000 from the Fourth Presbyterian Church. Their two sons felt such shame at their parents’ actions that they both committed suicide.

“Money really cannot buy you everything,” Jean said.

But there’s a glimmer of happiness in this sad tale. Enter Seymour Persky, the philanthropist who swooped in and saved the mansion from demolition. He was a lawyer-turned-developer who made a fortune and then dedicated his life to collecting architectural artifacts, bless his heart.

The servants would do prep work in the butler’s pantry, where they could stay out of sight but still keep an eye on how dinner was progressing.

Off the dining room is the butler’s pantry. My favorite detail: the narrow window in the door, where the help could keep an eye on the diners’ progress.

“During the Victorian era, they say children should be seen and not heard. I think servants were supposed to be neither seen nor heard,” Jean said. “They just sort of floated in when they needed to take a plate away.”

The Charnleys’ sitting room is now home to the Society of Architectural Historians library.

The Sitting Room

The highlight of the sitting room (now the SAH library) is the gorgeous tiger stripe white oak paneling. It’s called “tiger stripe” because it looks like, well, a tiger’s stripes. The wood didn’t come cheap. It’s cut from quarter-sawn wood, which is basically like slicing a citrus fruit into wedges. This is wasteful, but it brings out the beautiful and distinct grain pattern. Keep in mind, though: Charnley was a lumber baron, and wood was certainly an area where he could splurge.

At the time, the biggest commodities in Chicago were meat, wheat and lumber. While at least 200 lumber schooners entered the Chicago River every day, the industry had started to decline. The northern forests of white oak in Michigan and Wisconsin had been depleted. And on the day of the Chicago Fire, there was also a huge fire in Peshtigo, Wisconsin, a lumber mill town, which burned to the ground.

People switched to Southern yellow pine, and the industry dispersed instead of being centralized in Chicago.

The benches, cabinets and leaded glass in the sitting room are all original.

There’s another beautiful fireplace in here, this one with carved oak leaves. And again, African rose marble.

Those scrolling leaves are pure Sullivan, but it’s believed that the geometric design in the middle of the sitting room fireplace woodwork was most likely a Wright touch.

One detail that experts believe came from Wright is the geometric ornamentation of the fireplace panels. It’s unlikely that Sullivan would have conceived the pointed arches and flat, almost Gothic stylized leaves, as this is an arrangement that one would expect from Wright.

The star of the show: The amazing screen that somewhat hides the staircase is one of the elements attributed to Wright in the home’s design.

Upstairs: The Staircase, Bedrooms and Balcony

In my opinion, the most striking part of the home is the staircase. The stairs are set back a bit behind a screen of slender oak spindles, so they appear to be floating. “It’s a beautiful way to illuminate the stairs without closing them off,” Jean said, adding that scholars believe this may have been a Wright touch as well.

Upstairs are two bedrooms, access to the balcony and beautiful (if a bit precarious) woodwork looking down to the first floor. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

The bedrooms are now offices for the architectural society. The rooms themselves aren’t overly impressive, with small unadorned fireplaces ordered from a catalog. There was no need to impress others, you see; it’s the idea of private vs. public space. But they do boast unheard-of amenities at the time: Each has an en-suite bathroom and walk-in closet.

One interesting tidbit: Unlike most homes of the wealthy at the time, James and Helen shared a bedroom. But we knew they had modern sensibilities when they hired Sullivan to design the home.

Another staircase in the back corner of the landing leads all the way from the basement to the fourth floor, where the servants’ bedrooms were located. They were about half the size of the other bedrooms. While you might think the servants had it nice since the top floor has the best view, just remember that there wasn’t any air conditioning — and heat rises.

The only real outdoor space found at the Charnley-Persky House is the front balcony. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

The balcony was the only outdoor space. Because the house is close to the lake (and this is the Windy City, after all) there’s always a nice breeze. It looks west, to what was a shop across the street. “Not much was going on,” Jean said. “And then Little Hell. So you didn’t need to see too far.”

That pinkish-putty brown color (Jean’s not a fan) matches the original hue of the balcony.

The house was given to the SAH, but unfortunately, there’s no endowment to support its upkeep. Tours, donations and the efforts of the architectural society subsidize the preservation of this magnificent house so that it can continue to be enjoyed for generations to come.

If you are a Chicagoan interested in architecture or history, or are visiting Chicago and looking for something to do after you’ve seen the Bean, book a tour to experience the birth of the modern home, designed by two of the world’s most famous architects.

The home is open for docent-led tours every Wednesday and Saturday at noon year round. There’s an additional Saturday tour at 10 a.m. from April to October. Tours are free on Wednesdays and cost $10 on Saturdays. Reservations are required and tours are limited to 10 people. –Wally

Look for this fence to enter the small sunken courtyard that leads to the visitors center to start your tour. Photo by Leslie Schwartz

Charnley-Persky House Museum

1365 North Astor Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

USA