Dive into the fascinating story behind Fallingwater, from its geological origins to its current status as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

The Kaufmanns on one of the balconies at Fallingwater: E.J., Junior and Liliane

Unlike our visit to Graycliff, another Frank Lloyd Wright-designed home, where the weather forecast called for rain but miraculously cleared up by the time we arrived, the conditions at Fallingwater were not so kind. But the steady mist-like drizzle coming down on the rooftop covering the Visitors Center boardwalk didn’t dampen our anticipation for the afternoon In-Depth Guided Tour of Fallingwater. The nonprofit Western Pennsylvania Conservancy (WPC) offers various tours, which include a one-hour guided house tour, two-hour in-depth tour, brunch tour and sunset tour.

Pro tip: Book your tickets at least two weeks prior to guarantee admission to this popular attraction. Weekends fill up quickly. We booked ours about a month in advance.

Our group gathered in the Visitors Center around our docent, who welcomed us to the UNESCO World Heritage Site and introduced himself as Rod. He asked where everyone was from and if anyone had been to any Wright-designed homes or buildings before. As we shared our stories, it became clear that we were among other individuals who held a reverence for the architect’s prolific and unmistakable style.

Kaufmann’s was once a legendary (and massive) department store in Pittsburgh. It’s now a Target.

Brought to You by Pittsburgh’s Big Department Store

Edgar J. Kaufmann and his wife, Liliane, the couple who commissioned Fallingwater, were also the owners of a popular Pittsburgh department store located at the corner of 5th Avenue and Smithfield Street. Like Marshall Field’s in Chicago, Kaufmann’s was a regional destination for shoppers to discover the latest in fashion, art and design.

In 2005, Federated acquired the store and continued to operate as Macy’s until 2015, when it closed its doors for good. The first floor has since been transformed into a Target, which opened in the summer of 2022.

The Kaufmanns were wealthy, but they were also beloved in southwestern Pennsylvania. Their department store brought good taste and good design to the area at prices that people could actually afford. They were popular for their business model: They’d rather sell a hundred items at a penny profit each than sell one item for a dollar profit.

The dramatic cantilevers at Fallingwater are Wright’s way of mirroring the sandstone outcroppings in the area.

From Sea to Timeworn Sandstone: A Brief Geological History of the Site

Rod offered us green umbrellas to take with us on our journey. “From experience,” he added, “make sure it works. Our umbrellas lead a pretty tough life here.” The color of the umbrellas complemented the natural surroundings, a detail that Wright himself would have undoubtedly appreciated. As we followed Rod down the gravel path leading to Fallingwater, he spoke about the geologic history of the site.

He stopped and gestured to the lush, hilly landscape before us. “As we walk down towards the house, I’d like to provide a brief timeline for you,” he began. “We’re standing at 1,400 feet above sea level due to a cataclysmic event that occurred over 400 million years ago.” He continued, “The tremendous pressure of the continental plates colliding caused the Earth’s surface to fold and buckle, creating the long, winding ridges of the Appalachian Mountains.

“However, 600 million years ago, this region was at the bottom of a sandy, shallow inland sea. Over millions of years, the inland sea drained, and the mountains were worn down by wind, weather and water,” Rod said. “The sedimentary deposit that was left behind was compacted and compressed to form Pottsville sandstone.”

Wright first visited the site of Fallingwater with Edgar Kaufmann Sr. to examine the natural landscape. He saw the weathered, horizontal lines of the sandstone outcroppings and referred to this as the “earth line” — and it became the inspiration for the layered stone walls and cantilevered terraces that mirror the natural environment.

Cantilever, you ask? It’s something that projects horizontally beyond its support, like a diving board, firmly anchored at one end and floating free at the other. You’ll see they feature prominently in the home’s design.

One of the original wood cabins at what became Camp Kaufmann

Setting Up Camp at Bear Run

The Kaufmanns would flee Pittsburgh’s sweltering summers and infamously smoky air for the rolling hills and clear streams of Fayette County, Pennsylvania. In 1916, E.J. Kaufmann, as Edgar Sr. was known, began leasing a parcel of land at Bear Run from the Pittsburgh Freemasons. The grounds included the former Syria Country Club lodge, which E.J. renamed Camp Kaufmann.

Every summer, a third of Kaufmann’s department store employees would visit and stay in one of the many cabins that dotted the property. The camp was a place for employees to relax and enjoy the outdoors. They would hike, swim, fish and play games.

Not a bad perk: Employees of Kaufmann’s department store could go to the camp in the woods and swim under the waterfall.

Used with permission from the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

In 1926, Kaufmann’s department store purchased the land and cabins from the Freemasons. However, the Great Depression forced it to quickly get out of the camp business. So, in 1933, E.J. assumed ownership of the land with the intent of building a modern weekend home. That same year, he showered his mistress Josephine Bennett Waxman with a quarter-million dollars’ worth of diamond and platinum jewels. The affair fizzled, but made headlines when E.J. attempted to return the jewelry to rival department store Horne’s, which sued him for non-payment.

Edgar jr. (left) worked for Wright (center) at Taliesin in Wisconsin. He introduced the architect to his father — and a beautiful partnership was begun.

As fate would have it, his artistically inclined son, Edgar jr., was studying with Wright at the Taliesin Fellowship in Spring Green, Wisconsin. During that time, Junior introduced his parents to the architect, and E.J. and Liliane decided to hire Wright to design their new home.

When Wright was hired to design Fallingwater, E.J. also commissioned him to create his executive office on the top floor of the flagship department store in Pittsburgh. It’s now on display at the Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

Used with permission from the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy

A Patronage of Epic Scale

The Kaufmanns and Wright were kindred spirits. They shared Wright’s conviction that good design could transform the lives of those it touched and believed that architecture should be in harmony with the natural world. Wright was a passionate advocate for organic architecture. He believed that buildings should be designed to complement their natural surroundings, and he often used local materials and natural forms in his designs. He once said, “I believe in God, only I spell it Nature.”

By the time E.J. met the architect, Wright was 67 years old and had not completed a major project in a decade. He was widely considered a has-been by architectural critics — but Fallingwater would mark a turning point in his career.

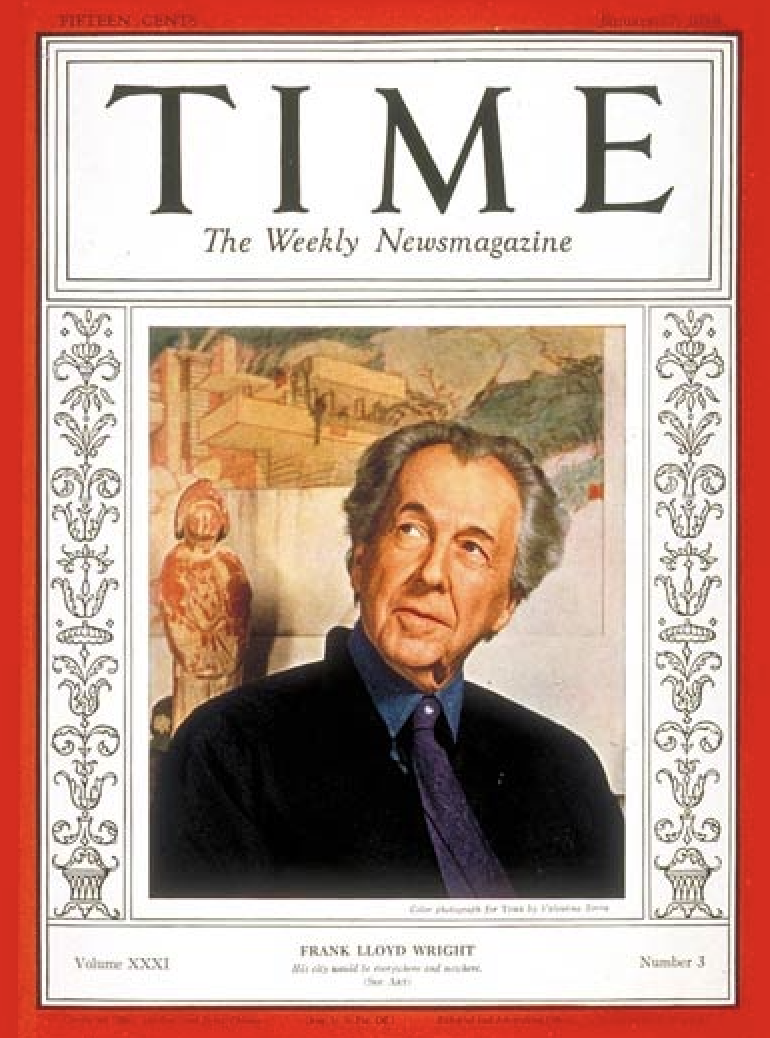

Talk about a comeback: Wright and Fallingwater on the cover of Time

The woodland retreat in rural southwestern Pennsylvania had already gained international prominence before it was even completed. In January 1938, photographs taken by John McAndrew were exhibited at the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York City and subsequently published in Architectural Forum magazine. Additionally, Wright was featured on the cover of Time with his drawing of Fallingwater behind him, proclaiming it to be his most beautiful work.

After the success of Fallingwater, Wright’s career took off again. He went on to design over 400 projects, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York. Of these, approximately 200 were built, and about 79 have since been demolished or destroyed by fire. Wright died in 1959 at the age of 91.

Wright and E.J. maintained a lifelong friendship and collaborated on many projects, although only three of them were ever realized: Fallingwater, the guest house and Edgar’s executive office.

Not without my dachshund! Liliane liked to bring her six dogs on weekends at Fallingwater.

The Kaufmanns’ main home, La Tourelle, was an Anglo-Norman style country estate in Fox Chapel, an affluent suburb of Pittsburgh. The family had two options to reach their weekend home. They could take a train from Pittsburgh to the depot at the bottom of Bear Run, where the creek flows into the Youghiogheny River. (The last time the B&O line stopped here was in 1975). Or they could be chauffeured by car. Liliane preferred the latter because she liked to travel with her six long-haired show dachshunds.

Before his death, Edgar jr. entrusted Fallingwater to the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy so it would always remain open to the public for all time.

Fallingwater: A Landmark Legacy

The house that has become an architectural legend was home to tragedy, though. On September 7, 1952, Liliane died of a sleeping pill overdose at Fallingwater at the age of 64. Three years later, E.J. died of bone cancer at 69. Their son, Edgar jr., inherited Fallingwater.

The Kaufmanns didn’t have the best marriage. Edgar’s infidelities may have led Liliane to take her own life by overdoing on pills at Fallingwater.

Junior worked at MoMA from 1941 to 1955 and was an adjunct professor of architecture and art history at Columbia University in New York.

In 1963, he entrusted the house and surrounding 5,100 acres of property, along with a $500,000 endowment, to the WPC to protect, conserve and, most importantly, assure that the home remains open to the public in perpetuity.

Junior was gay and had a long-term relationship with Paul Mayén, a Spanish architect and industrial designer. Mayén's influence can be seen throughout the sunburst-shaped visitors pavilion, which was built under his supervision in 1980 by the Pittsburgh-based architectural firm Curry, Martin & Highberger. The complex complements its natural surroundings and makes great use of materials such as cedar, glass and concrete. I think Wright would have approved.

Paul Mayén, Edgar jr. and friend on the west terrace at Fallingwater. The men had a relationship for over 30 years.

Used with permission from the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy.

Edgar jr. loved Fallingwater and when he visited Pittsburgh, he would often come and secretly lead tours. At the end of each, Rod told us, Junior would shock the group by asking, “Well, what do you think of my house?” –Duke

RELATED: Frida, Diego and Fallingwater

Frida Kahlo visited Fallingwater (and seduced a fellow guest there!).

Learn more about her and Diego Rivera’s connection to the Kaufmanns and their iconic home.