Sé what? Where St. Anthony was baptized, St. Vincent’s relics rest, and a bishop got tossed from the tower — Lisbon Cathedral holds centuries of stories in its stones.

The Sé de Lisboa was built on the site of a former mosque shortly after King Alfonso Henriques conquered the city from the Moors in 1147 CE.

Perched on a hillside in Lisbon’s Moorish Alfama quarter, the Basílica de Santa Maria Maior (Cathedral of Saint Mary Major), commonly known as the Sé de Lisboa (Lisbon Cathedral), serves as the seat of the Patriarchate of Lisbon and the city’s most significant surviving example of medieval architecture.

Construction of the national monument began shortly after King Afonso I and his Portuguese forces, aided by Christian crusaders, wrested the city of al-Usbūna from Islamic rule in 1147 CE, renaming it Lisboa.

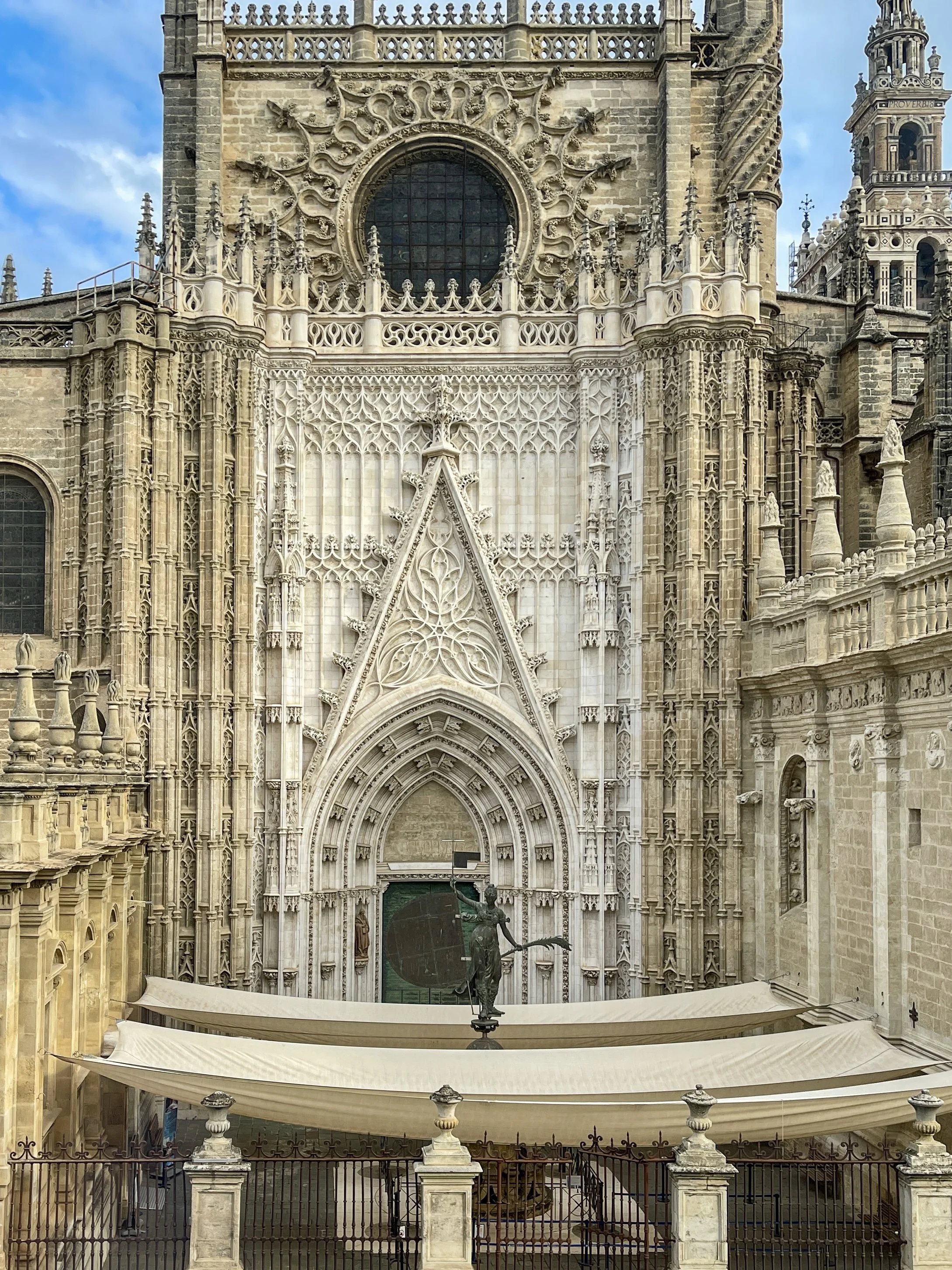

Jagged, tooth-like crenellations give the cathedral’s Romanesque façade a fortress-like appearance. But if you look closely, you’ll see rounded arches and sets of slender columns topped with sculpted capitals.

The Façade of the Sé

Wally and I stumbled upon the imposing landmark as we made our way downhill after spending the morning exploring the hilltop ramparts of the Castelo de São Jorge (St. George’s Castle). The stone walls of the cathedral stretched so far along the Rua de São Tomé that I wouldn’t have been surprised if a local had told us they were once part of the Old City Wall.

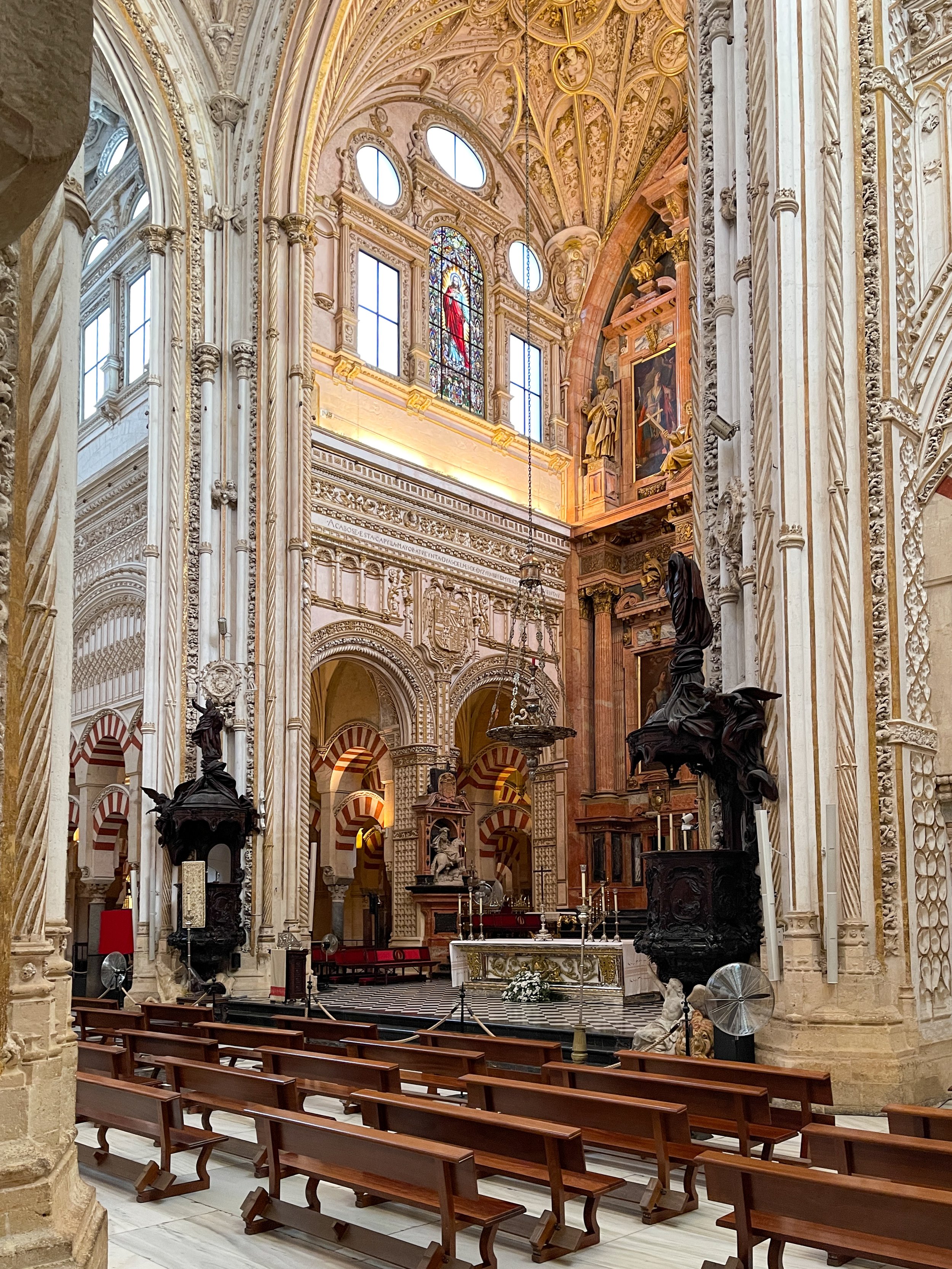

The choir loft of the Sé de Lisboa offers a spectacular view overlooking the barrel vaults of the central nave and main altar.

From the western façade, the cathedral looked every bit like a fortress: a pair of stout towers flanked the entrance, narrow arrow-slit windows punctuated the stone walls, and jagged, tooth-like crenellations crowned the top. But as we drew closer, the stepped, concentric arches of the main doorway and the delicate tracery of the rose window above made it clear this was, unmistakably, a church.

Constructed largely from limestone blocks, the original Romanesque structure was completed between 1147 and the early 13th century. Its fortified appearance was no accident: In an era when sacred spaces often doubled as defensive strongholds, the Sé offered not only spiritual refuge but also a strategic vantage point in the event of siege.

Originally destroyed in the 1755 earthquake, the rose window at the Sé de Lisboa was reconstructed in the 1930s using fragments of the original and features a central image of Jesus, surrounded by the 12 Apostles.

Entering the Sé

Once inside, we made our way to the ticket counter and paid admission before ascending the staircase to the church tower leading to the Coro Alto (High Choir) loft and Tesouro da Sé (Treasury Museum).

The cathedral’s high altar was redesigned in the late 18th century in the ornate Baroque style.

Along the way, we paused to gaze at the spot where a young Fernando Martins, later Saint Anthony of Padua, was said to have been tempted by the Devil. Tradition holds that he drew the sign of the cross on the wall to repel Satan, a mark now framed by decorative ironwork and accompanied by a plaque recounting what is said to be the first of many miracles attributed to the Lisbon-born saint.

The High Choir didn’t disappoint, offering a spectacular vista. From there, Wally and I enjoyed a bird’s-eye view of the orderly Romanesque barrel vaults, central nave and Baroque chancel, and could clearly see the magnificent rose window depicting Christ surrounded by the Twelve Apostles. Created in the 1930s by the atelier of Ricardo Leone, the window’s design was based on surviving fragments from the original, which had been destroyed in the catastrophic earthquake of 1755.

This statue depicts Saint Vincent of Zaragoza, the patron saint of the Patriarchate of Lisbon, dressed as a deacon wearing a long red tunic and holding a book that evokes his role as preacher and protector of the Scriptures.

The Sé’s Treasury & Chapter House

In the treasury museum, four halls display a remarkable collection of religious objects spanning the cathedral’s long history, including reliquaries and other sacred artifacts. Among the most striking objects is the Custódia da Patriarchal (Patriarchal Monstrance), a solid-gold liturgical vessel whose design is attributed to João Frederico Ludovice, a German-born goldsmith and architect. Commissioned by King Dom João V, a devout Catholic who made it his life’s mission to turn Lisbon into a second Rome,

the monstrance is encrusted with more than 4,000 diamonds, rubies, sapphires and emeralds and weighs over 37.5 pounds (17 kilograms). It was used to display the consecrated host during mass and was meant to reflect both divine glory and the king’s ambitions for a richly adorned patriarchal church. I tried to get a good photograph of it, but the glare from the lights on the glass made it tricky.

The third hall served as the Sala do Capiítulo (Chapter House), built in the 18th century above the sacristy. It was here that the patriarchs gathered daily to hear the chapter recited, discuss the business of the order, and receive their assignments. The chamber also hosted weightier functions: deliberations, disciplinary proceedings and commemorations for members of the chapter who had died.

The fresco above the center of the Chapter House depicts a scene of the allegorical figures of Prudence, Peace, Victory and Justice — virtues meant to guide those who gathered there.

The room also includes a painting depicting the story of Judith and Holofernes — specifically the moment when Judith, one of the badass women of the Bible, having beheaded the Assyrian general in his tent, presents his severed head to the people of Bethulia.

Among the treasures of the Sé de Lisboa is a ceremonial sedia gestoria, a richly adorned, portable throne once used in processions by the Patriarch of Lisbon.

Among the treasures is a theatrical ensemble from the ceremonial apparatus of the papal court: a sedia gestatoria, the velvet-and-silk brocade throne on which popes were once carried, flanked by two flabella, great ostrich-feather fans. These fans signified honor but also served a practical purpose, to swat flies away from the consecrated host and the celebrant during liturgy.

Above, a Baroque fresco portrays a celestial allegory of the virtues expected of the cathedral chapter. At its center, positioned above the other figures, sits Prudence. Her mirror, the attribute that defines her, reflects the ideals of self-knowledge, truth and moral clarity.

Gathered around her are the remaining personifications of virtue. Peace appears as a female figure bearing an olive branch. Victory is depicted as a winged youth lifting a laurel-leaf crown. Justice, dressed in yellow, carries a bundle of rods bound with a ribbon, the traditional emblem of fair and measured authority.

This painting depicts a scene from the Book of Genesis: Eliezer meeting Rebecca at the well, a common subject in Christian devotional art.

Construction of the Cathedral

After exploring the treasury, we headed back downstairs and into the cathedral proper. It should be noted that the Sé de Lisboa has never been a static monument. The transept retains its original Romanesque vaults, though 20th century interventions introduced archways and a pair of stained glass windows depicting the city’s patrons: São Vicente (Saint Vincent) and Santo Antonio (Saint Anthony).

Over the centuries, the cathedral has been rebuilt, reinforced and reimagined, shaped as much by changing architectural taste as by the forces of nature. The great quake of 1755, along with earlier earthquakes in 1344 and 1356, left it with significant structural damage. The result is an astonishing blend of Romanesque, Gothic and Baroque styles.

The Baroque 18th century painting above the high altar depicts the Assunção da Virgem (Assumption of the Virgin) and is attributed to José Inácio de Sampaio.

The octagonal dome over the high altar dates to the post-1755 reconstruction, adapted from what was once the cathedral’s bell tower. The Baroque chancel was created during that same campaign, replacing the Gothic chapel lost in the quake. In the 17th century, new side altarpieces were also added and later reworked, including one dedicated to the Virgem Maria (Virgin Mary) and another honoring Saint Anthony of Lisbon completed between 1769 and 1771 by the architect Reinaldo dos Santos.

Located in the cathedral’s transept and installed during a 20th century restoration, these stained glass windows honor Lisbon’s patron saints: Saint Vincent (left) and Saint Anthony (right).

RELATED: Artistic Depictions of the Virgin Mary: From Queen of Heaven to Lactating Mother

The earliest phase of construction of the Sé began under Gilbert de Hastings, an English crusader appointed bishop after the 1147 reconquest of Lisbon. The master builder Mestre Roberto is credited with designing the original Romanesque church: a Latin cross plan with three aisles, a transept and a main chapel encircled by an ambulatory.

The Gothic cloister was added during the reign of King Dinis, around 1261, and completed in the early 14th century. His successor, King Afonso IV, transformed the main chapel into a royal pantheon for himself and his wife, Queen Beatriz, and commissioned the construction of the apse, the semicircular east end of the cathedral, and its surrounding ambulatory. Located behind the high altar this corridor is covered with ribbed vaults and lined with nine radiating chapels, each dedicated to a different saint. Built between 1325 and 1357, the complex was designed to accommodate the growing number of pilgrims who came to venerate the relics of St. Vincent.

Of Ravens and Bones

Born in Huesca (or Zaragoza) in the early 4th century, Vincent of Saragossa was arrested by Roman authorities and taken to Valencia, where he was martyred during Emperor Diocletian’s persecutions. According to tradition, he was tortured, roasted on a gridiron, and left for scavenging birds — but ravens guarded his body. Christians later recovered his remains, and devotion to his cult spread quickly across Christendom.

This decorative plaque commemorates the legendary voyage of the relics of Saint Vincent of Zaragoza to Lisbon, and features a caravel flanked by two ravens. It’s said that ravens protected the martyr’s body on the ship bringing his remains to the city.

Centuries later, King Afonso I sought a significant relic to legitimize his conquest of Lisbon. He dispatched emissaries to the Algarve to retrieve St. Vincent’s remains from their coastal shrine and transport them north by sea. When the relics arrived in 1173, Afonso declared Vincent the patron saint of Lisbon.

According to legend, a pair of ravens accompanied the vessel carrying his remains. The story endures, and the image of a stylized caravel flanked by a raven at each end appears throughout the city, including on street lamps and in Lisbon’s coat of arms.

The tomb in the Capela de Santa Ana (Chapel of St. Anne), is more of a mystery, believed to belong to an unidentified royal princess.

Although the tombs of Alfonso IV and Beatriz of Castile were destroyed in the 1755 earthquake, the cathedral’s Gothic ambulatory still contains three remarkable mid-14th century tombs. Two lie in the Capela de São Cosme and São Damian (Chapel of Saint Cosmas and Saint Damian), twin brothers born in Syria, traditionally venerated as early Christian physicians who offered their services for free, and considered patron saints of surgeons, pharmacists, veterinarians and barbers.

The effigy of Lopo Fernandes Pacheco portrays him as a dignified noble knight, his long, well-groomed beard emphasizing status, maturity and authority.

The sepulcher of Maria de Villalobos depicts her recumbent effigy reading from a book of hours.

The chapel holds the funerary monument of Lopo Fernandes Pacheco, 7th Lord of Ferreira de Aves, a nobleman in Alfonso IV’s service; his recumbent effigy figure rests with a sword at his side, faithfully guarded by a dog at his feet. His wife, Maria de Vilalobos, lies in the adjacent tomb, depicted in serene contemplation as she reads from a book of hours. Above her, an elaborate Gothic, cathedral-like structure rises above her head — a symbol of the soul’s passage into the heavenly realm.

Saint Sebastian, a Christian martyr often depicted tied to tree trunk and pierced with arrows, has long been celebrated in art as a representation of resilience.

The Chapel of São Sebastião (Saint Sebastian) contains a Baroque marble sculpture of the early Christian martyr. The figure is depicted as a muscular, nearly nude young man, bound to a tree and pierced by arrows. In Christian art, these arrows symbolize both the torments he endured and, more broadly, the saint’s role as a protector against plague, since arrows were long used as metaphors for sudden, deadly illness.

The Chapel of Santa Maria Maior (Saint Mary Major) features a polychrome wood sculpture of the Virgin and Child and likely dates to the 16th or 17th century.

A Bishop’s Fatal Fall From Grace

By the late 14th century, the cathedral had survived its share of natural disasters. But in December 1383, it found itself at the center of a political one. King Fernando I’s death plunged the city into turmoil, ending the Burgundian dynasty and triggering a bitter succession crisis.

The monarch died without a male heir, leaving the throne in doubt. His only child, Beatrice, was married to Juan I de Castilla (King John I of Castile). If she succeeded, Portugal risked being absorbed into Castilian rule — an outcome many feared would erase the kingdom’s hard-won autonomy.

At the cathedral, tensions coalesced around its bishop, Martinho de Zamora (also known as Martinho Anes), a Castilian cleric suspected of favoring a Castilian takeover. In a moment when national sovereignty and political legitimacy hung in the balance, his perceived loyalties made him an easy target.

According to the royal chronicler Fernão Lopes, a furious mob stormed the cathedral, seized Bishop Martinho, and threw him from the north tower. Lopes recounts with stark detail that his body was dragged through the streets and left to be devoured by dogs — a grim prelude to the civil war and eventual rise of Portugal’s new dynasty under João I, which laid the foundation for the house of Aviz.

The Chapel of Idephonsus holds a painting Saint Ildephonsus receiving a chasuble, the outermost priestly vestment worn during mass, from the Virgin Mary, a gift honoring his defense of her perpetual virginity.

In 1498, Queen Eleanor of Viseu founded the Irmandade de Invocação a Nossa Senhora da Misericórdia de Lisboa (Brotherhood of Invocation to Our Lady of Mercy) in one of the chapels of the cloister of the cathedral. This brotherhood evolved into the Santa Casa da Misericórdia de Lisboa (Holy House of Mercy), a Catholic charitable institution that later spread to other cities and had a very important role in Portugal and its colonies.

Whether or not you’re into Catholic costuming, the carved gilt-wood Baroque altarpiece is reason enough to visit the Patriarch's Dressing Room.

The Patriarch’s Dressing Room

We paused to admire the Camarim do Patriarca (Patriarch’s Dressing Room), the space where the Patriarch of Lisbon — the city’s archbishop and one of Portugal’s highest-ranking church officials — prepared for mass. Upon arriving at the Sé, a bell announced his presence. He would first step into an antechamber to put on the cáligas, sandals matching the color of the day’s liturgical vestments, and the falda, a wide, flowing white tunic. From there, he proceeded into the dressing room to don the remaining vestments, including the cope, a full-length semicircular cloak, and the mitre, the tall, pointed ceremonial headdress with two trailing strips of cloth called lappets.

Located near the cathedral entrance, the Pietà depicts the Sixth Sorrow of the Virgin Mary as she holds the body of Jesus after the crucifixion.

Even though the cathedral wasn’t originally on our list, stumbling onto it was a wonderful surprise. We especially loved wandering through the quiet side chapels and discovering the ones that served as tombs. The Sé is absolutely worth popping into after an early morning visit to the castle just up the hill. –Duke

Near the cathedral entrance, surrounded by blue and white tile panels, stands the baptismal font where both Saint Anthony and Padre António Viera, a prominent 17th century Jesuit priest, were christened.

Before You Go: Lisbon Cathedral (Sé de Lisboa)

Cost

Main nave: Free for prayer

Museum and high choir:

€7 for adults (about $7.40)

€5 for children ages 7–12 (about $5.80)

Free for children under 6

Hours

Vary by season and by day (mass, choir services and special events can limit access)

Check the official site before visiting.

Accessibility

The main nave is accessible, but some areas — especially the museum and high choir — require climbing stairs.

Cobblestone streets around the cathedral can also be challenging.

How long to spend

We spent about an hour wandering through the museum and cathedral.

Lisbon Cathedral (Sé de Lisboa)

Largo da Sé 1

1100-585 Lisbon

Portugal