The 9th century minaret-turned-bell-tower of the Mezquita offers spectacular 360-degree views of the UNESCO World Heritage Site.

We chose to visit just before sunset to get some of that golden hour glow.

In the heart of Córdoba’s Historic Quarter stands a towering sentinel: the Torre Campanario de la Mezquita-Catedral de Córdoba, or the Bell Tower of the Mosque-Cathedral of Córdoba. Rising 54 meters high — equivalent to a 16-story building — this remarkable landmark claims the distinction of being the city’s tallest structure.

Formerly a mosque minaret, the bell tower stands as a living testament to Córdoba’s fascinating and diverse past. Visitors can climb to new heights and experience breathtaking vistas from the two uppermost levels of the tower.

The original minaret didn’t stand in the exact location of the bell tower, but it was close by and accessible from within the Patio de los Naranjos

A Brief History of the Minaret of the Great Mosque

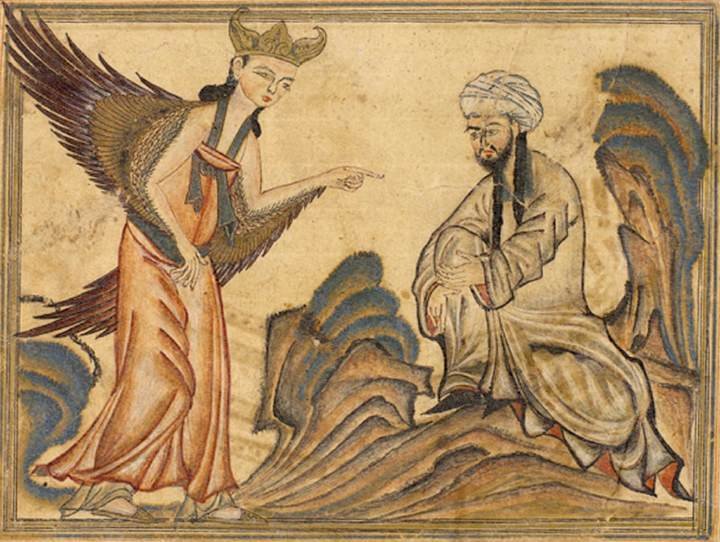

But first, let me take you back to the year 957, during the period of Muslim rule in southern Spain (or al-Andulus). Abd ar-Rahman III (891-961), the first caliph of the Umayyad Dynasty in Spain, had a new alminar — a minaret tower — built along the north wall of the mosque. This tower, where the muezzin calls the faithful to prayer, replaced the original one built by Hisham I (757-796) in the 8th century. Hisham’s tower had stood in the Patio de los Naranjos, the Courtyard of the Orange Trees, and was removed when the courtyard was expanded.

The architectural marvel likely resembled Sevilla’s La Giralda and had a rectangular shaft with a square base, an open-air platform, and a smaller secondary structure topped by an iridescent chevron-patterned bronze dome. At its summit, a yamur — an iron finial with metal spheres of decreasing size — was placed to protect the mosque from evil.

The original yamur and cross from the Reconquest are displayed alongside a scale model of the minaret built by Abd ar-Rahman III at the Museo Arqueológico de Córdoba.

However, a century after Abd ar-Rahman III’s reign, the Umayyad Empire teetered on the verge of collapse amid the chaos of civil war. Ferdinand III of Castile and his armies seized this opportunity, taking Córdoba by force on June 29, 1236. This pivotal moment marked the fall of the Great Mosque, which was converted into the Catedral de Nuestra Señora de la Asunción, the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption, dedicated to none other than the Virgin Mary. As a political declaration of victory, a Christian cross was placed atop the minaret’s yamur, a potent gesture marking the reconquest of the Catholic monarchy over its Islamic predecessors, with the alminar serving as the cathedral’s bell tower.

Vista de Córdoba (View of Córdoba) by François Boussuet, painted in 1863, depicts the Guadalquivir River, the Roman Bridge and a view of the Mezquita-Catedral’s bell tower.

Monumental Changes: The Minaret Becomes The Bell Tower

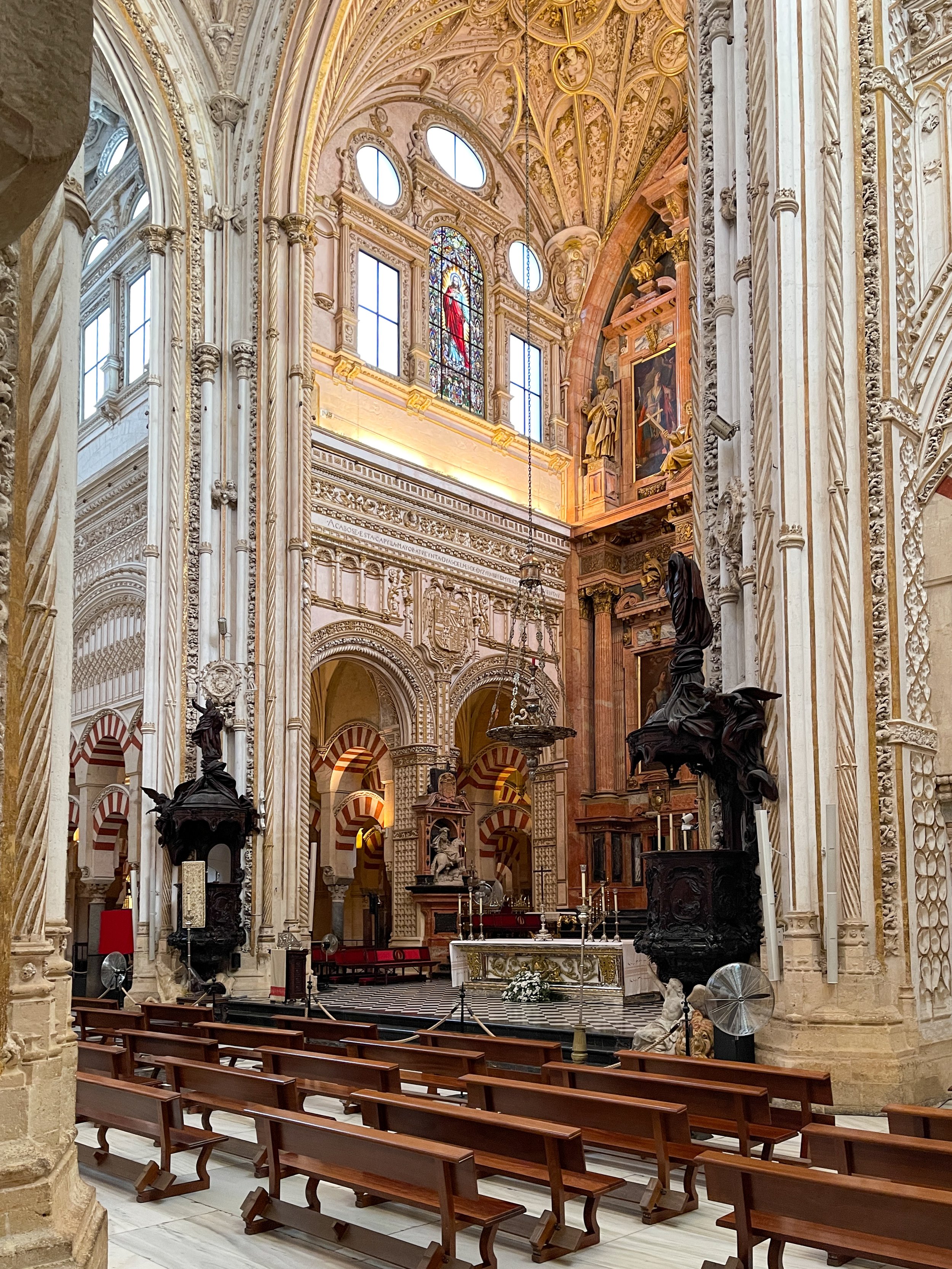

The Mezquita remained mostly unchanged under the Castilian Christians until 1523, when Bishop Alonso de Manrique petitioned Charles V and obtained his approval to construct the massive Capilla Mayor and Coro Crucero — the main chapel’s cruciform nave and transept — a full-fledged cathedral placed rather unceremoniously at the center of the former mosque.

An earthquake in 1589 left the bell tower unstable, leading to the decision to encase the structure. It was rebuilt and enlarged in the prevailing Renaissance style, under the direction of Hernán Ruiz III, the grandson of Hernán Ruiz the Elder, who had overseen the construction of the aforementioned Capilla Mayor. The lower half of the tower façade is marked by false windows, an architectural feature with horizontal lintel beams, bottom sills and indentations where a window might have gone. Additionally, it displays the various coats of arms belonging to the Cathedral Chapter, the patrons who financed the refurbishment.

The fourth tier, or belfry, features a serilana — a window with three openings. This architectural element is distinguished by a central arched window flanked by a pair of rectangular ones and offers a glimpse of the 12 bells within. Above this are two oculi, small ovoid openings echoing the exterior façade of the Capilla Mayor. Construction halted multiple times as funds were redirected to complete the Capilla Mayor. Unfortunately, Ruiz didn’t live to see its completion, but I think he would’ve been pleased with the final outcome.

Construction resumed in 1616 under the direction of architect Juan Sequero de Matilla. This phase included the addition of the smaller clock tower tier housing a pair of bells used to mark the passage of time. Its exterior is framed by pilaster columns topped by a triangular pediment, shields bearing the coat of arms of Bishop Diego de Mardones and arched windows in the middle of each side.

Almost five decades later, Gaspar de la Peña was tasked with repairing the south and west façades of the bell tower. He added the circular cupola to the clock tower and a figure representing Córdoba’s patron saint, San Rafael, attributed to sculptors Pedro de Paz and Bernabé Gómez del Río, at the top.

While the tower has undergone various restorations, the most comprehensive conservation effort to date commenced in 1991, when the building was closed, not reopening until 2014.

Where else would you get the best view of this charming town than from its tallest building?

How to Visit and Climb to the Top

Following our early morning visit to the Mosque-Cathedral, we made a beeline to the kiosks beside the bell tower to secure tickets to climb it later that day. Wally purchased tickets for the 6 p.m. time slot (each priced at 3€, or about $3 at the time), figuring this would allow us to experience the enchanting “golden hour,” that magical time just before sunset.

This is how you access the staircase of the bell tower. Groups of 20 go every half hour.

Tickets can also be bought online. Tours commence every half-hour, running daily from 9:30 a.m. to 6:30 p.m. Don’t assume you’ll be able to go right up the tower; tickets tend to sell out well before each time slot. Only 20 people are permitted to enter per group, and you must leave after the allotted 30 minutes.

Keep in mind that tickets for the bell tower do not include entry to the Mosque-Cathedral, and vice versa.

RELATED: Learn more about Córdoba’s must-visit La Mezquita with its mesmerizing arches.

How many pictures can elicit gasps of astonishment like this one?

Before purchasing tickets, be aware of the following restrictions: Entry isn’t permitted for children under 7, those aged 7 to 14 must be accompanied by an adult, and elderly or individuals with health issues are advised against the climb.

You can gaze upon the Courtyard of the Orange Trees and the Mosque-Cathedral from one side of the bell tower and a view of the narrow streets of the Historic Quarter on the other.

The View From Above

Upon our return to tour the tower, we accessed it via Calle Cardenal Herrero and passed through the Puerta del Perdón, also known as the Gate of Forgiveness. Allegedly, pilgrims passing through this special passage received forgiveness for all their sins. The opulent Baroque-style vaulted ceiling is adorned with intricate plasterwork that includes cherubs, episcopal heraldry, tondos (circular reliefs with the images of the four Evangelists), and garlands of blue and gold flowers.

Crafted from pine and adorned with gorgeous geometrically patterned bronze plaques, the towering doors of the Gate of Forgiveness bear commemorative inscriptions as well as an elaborate door knocker.

There’s no elevator, and the ascent is 191 steps. It was manageable, though, for a couple of middle-aged guys in decent shape. Besides, you can pause at various levels on your way up if you’d like.

At one such place, we stopped to look down at a shimmering metal dome, before realizing it was the top of the old minaret!

The minaret’s original cupola, adorned by a Christian cross, can be seen as you climb the bell tower.

The magnificent views of town and the Patio de los Naranjos definitely make the tower worth adding to your itinerary. Stop to gaze out on each side, gaining a different but equally impressive vista from every direction.

Who’d have thought that this what the rooftop of the cathedral looks like?!

Wally preferred the fourth tier, where you can marvel at the machinations of the bell chamber. Each bell has a different tone and name — La Esquila, La Asunción and San Zolio, to list a few. Some are marked with their year of manufacture and some bear the insignia of the bishop who commissioned their casting.

Each of the bells is said to have its own nickname.

Don’t worry. Wally was just pretending the bells were ringing.

While gazing out at the city, we couldn’t help but notice a sweet aroma of caramelized sugar wafting up from the street below. After we had climbed back down, we walked along the street to investigate — and determined that it had originated from Sabor de España, a confectionery shop. It specializes in treats, prominently featuring glossy cherry-red candied apples in their street-side window, along with caramelized nuts and turrón nougat.

Verdict: Make time to visit the bell tower. The panoramic views of the city are worth experiencing and for us, it was the perfect way to wrap up our day of sightseeing in this wondrous city. –Duke