Try as he might, Thutmose III wasn’t able to completely eradicate references to his aunt Hatshepsut as his co-pharaoh. And why did he wait so late in his reign to do so?

Thutmose III tried to get rid of all references to Hatshepsut as pharaoh — but he couldn’t find them all, thankfully!

Hatshepsut was, undeniably, a remarkable woman. A princess who married her half-brother to become his queen. A high priestess (and symbolic wife) of the most powerful of the gods. A queen regent for her nephew (and stepson), Thutmose III. And then, in an unprecedented move, the most senior of two simultaneous pharaohs. She was, as Kara Cooney’s book title proclaims, The Woman Who Would Be King.

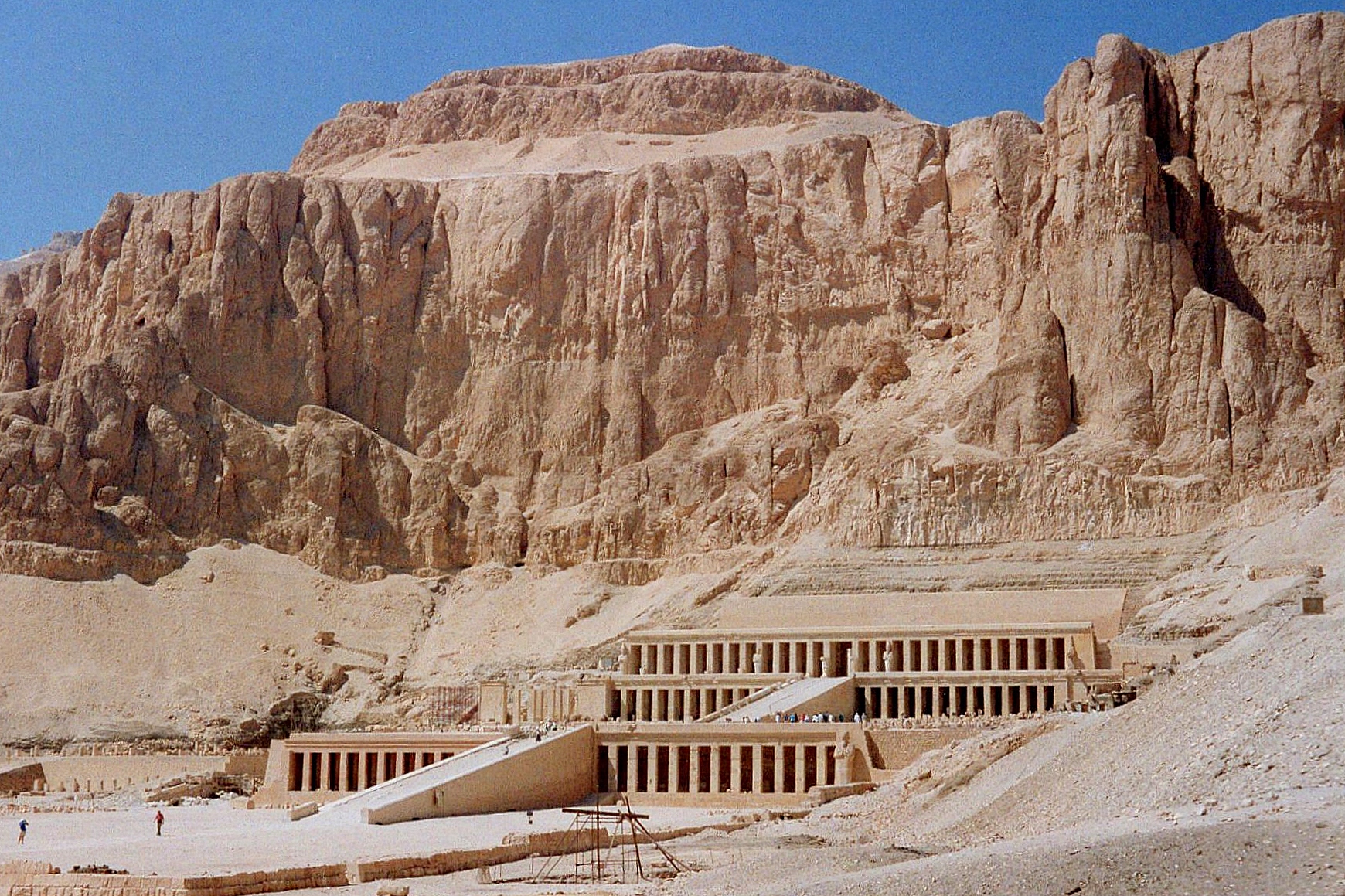

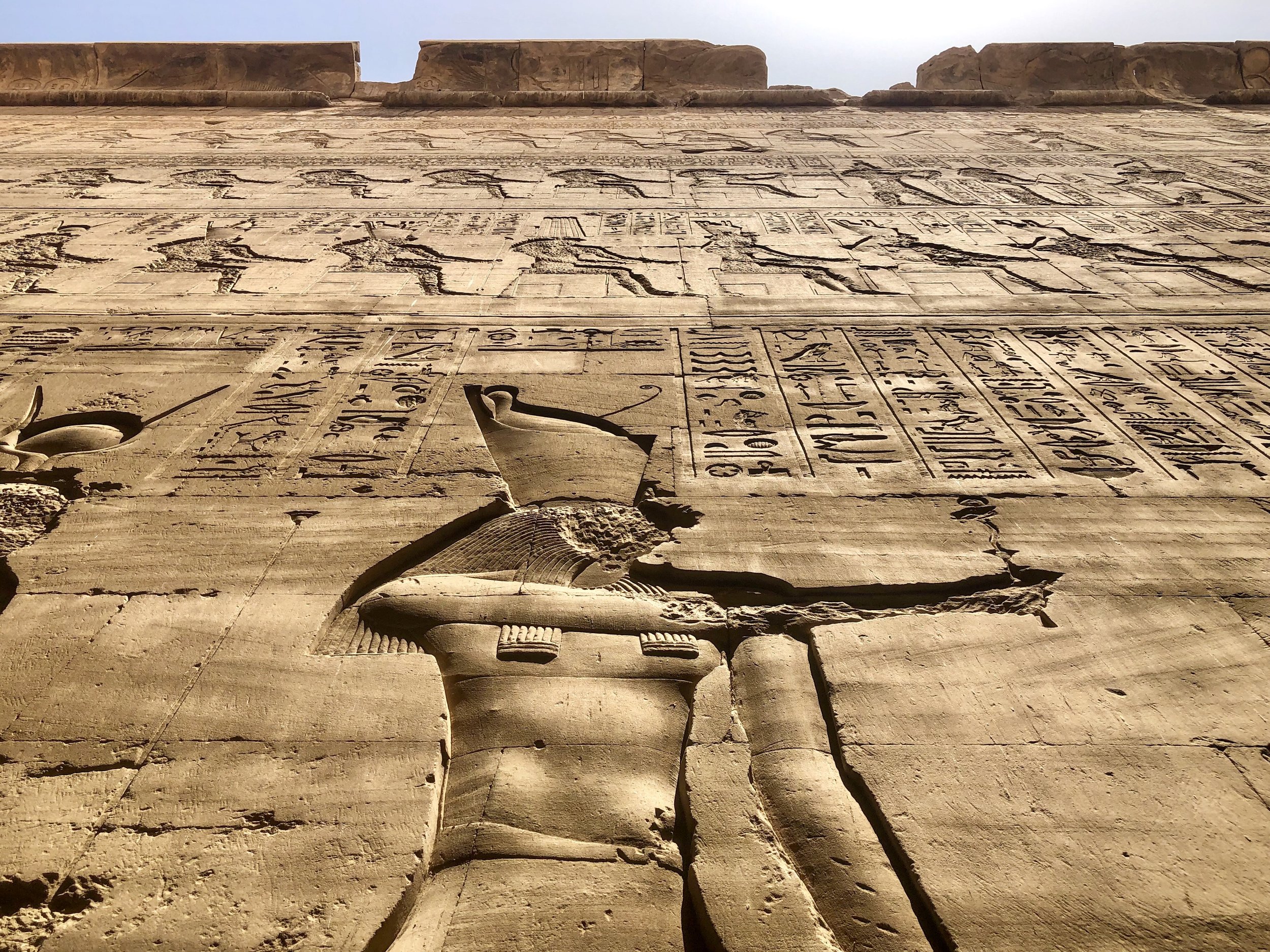

Duke stands in the ruins of Karnak Temple, a massive complex that Hatshepsut helped build (and, as such, once sported countless depictions of the female king)

Hatshepsut’s reign of 20 years was a time of peace and prosperity, during which the Two Lands of Upper and Lower Egypt experienced stability. Backed by military might, the country received goods from every direction, including Nubian gold. With the coffers full, Pharaoh Hatshepsut embarked on massive construction projects, putting her people to work building tombs and temples. Her image, which became more and more masculine, literally covered the country.

So it was quite ambitious to attempt to obliterate her legacy. But that’s exactly what her one-time co-ruler, Thutmose III, tried to do. The strange part is that he waited about 25 years after Hatshepsut’s death to do so. If he was so upset with his aunt/stepmother, why the delay?

Thankfully, Thutmose III, try as he might, ultimately failed to completely erase all mentions of Hatshepsut as king. Here are some of the fascinating facts that led to this complicated string of events.

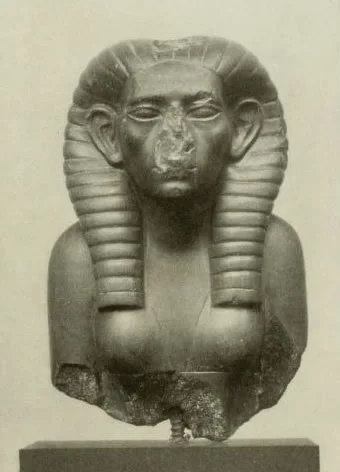

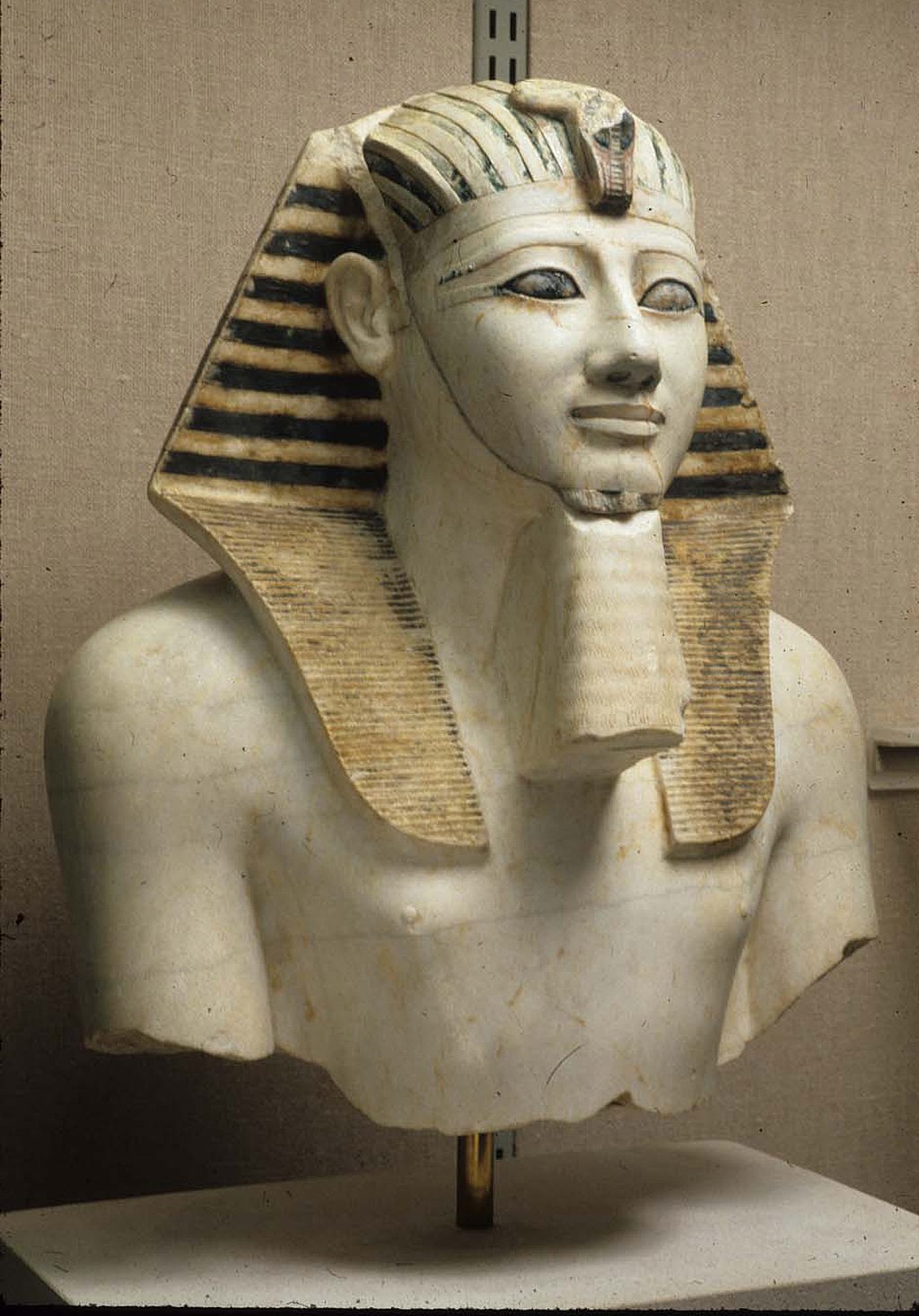

Like mother, like daughter: Evidence reveals that Pharaoh Hatshepsut, depicted here as a sphinx, attempted to pave the way for her daughter to ascend the throne

Hatshepset put her daughter Nefrure into the role of God’s Wife — probably hoping she would be her successor.

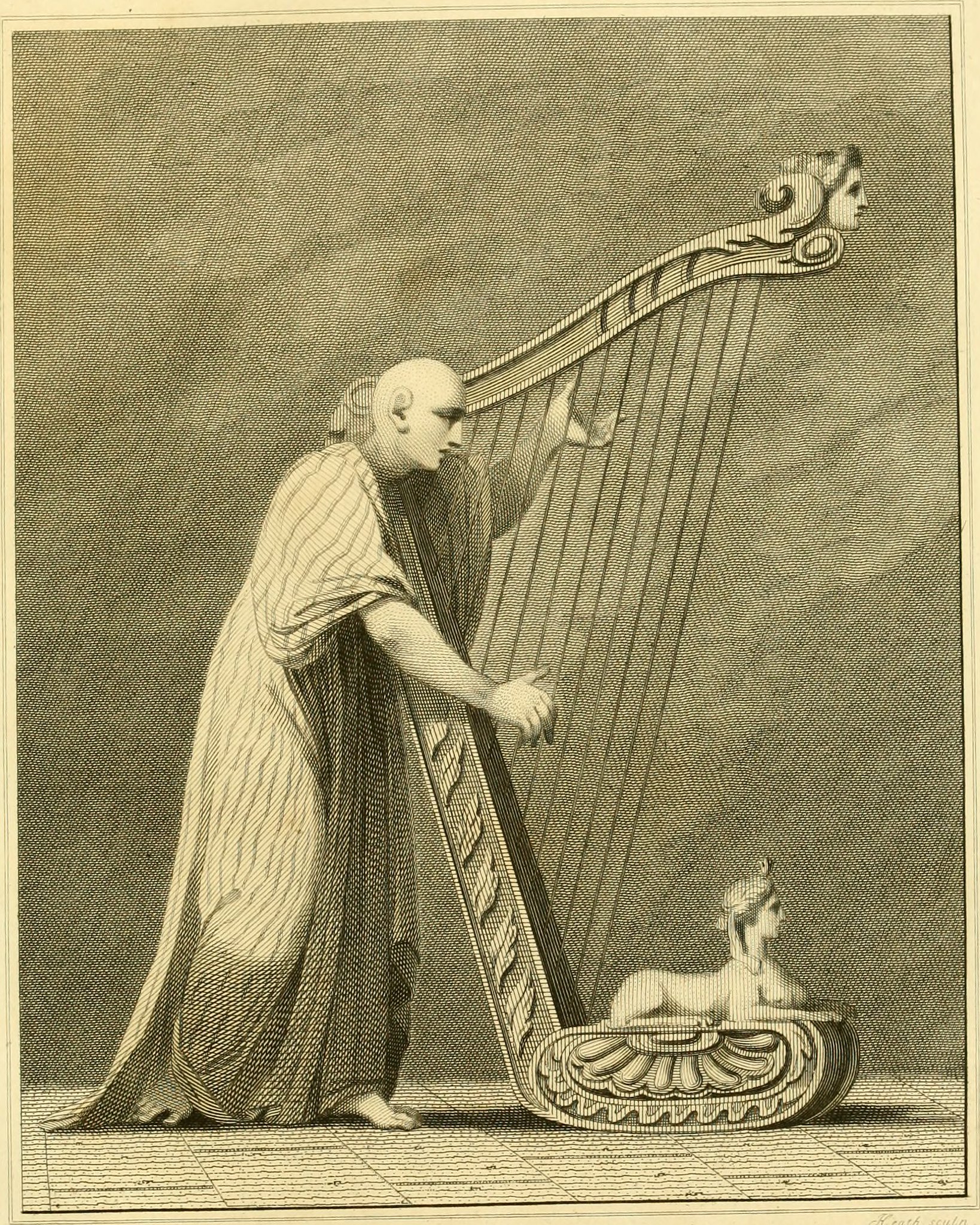

There are plenty of things a female ruler can do. But having a Great Wife like every male pharaoh before her isn’t one. But she could assign her child to one of the most powerful positions at the time: the high priestess of Amun (aka Amen).

“And so we see Hatshepsut performing her religious duties in the temple with the God’s Wife — offering up bloody haunches of freshly sacrificed calves, striking ritual chests with sacred instruments, or chanting transformational spells to the sun god on the hour,” Cooney writes.

There’s good evidence that Nefrure was also married to Thutmose III, so in a strange way, she was also acting as wife to her mother simultaneously — at least for ritual events, according to Cooney. “Poor Thutmose III: he had to share absolutely everything with his aunt Hatshepsut, even his own Great Royal Wife,” she writes.

Imagery of a woman at Deir el-Bahari, Hatshepsut’s funerary temple, is believed to be that of Neferure, offering a strong argument that Hatshepsut intended for her daughter to co-rule with Thutmose III as she did.

Those depictions were rather quickly scratched out or replaced with carvings of Thutmose I, Hatshepsut’s father, as is evident in the Chapel of Anubis at Deir el-Bahari.

“It is likely that Thutmose III, or the Amen priesthood, or some faction of elites resisted, fearing the creation of another strange male-female coregency, this time beyond the justification of necessity and dynastic security,” Cooney writes. “Hatshepsut apparently relented, bowing to political or religious pressures and ordering the removal of all such images from her funerary temple. Or maybe no one dared speak against the senior king at all. Nefrure might have died during her mother’s reign, ruining all such hope for an heir of her own lineage.”

There are hints that not everyone was too happy about a female pharaoh.

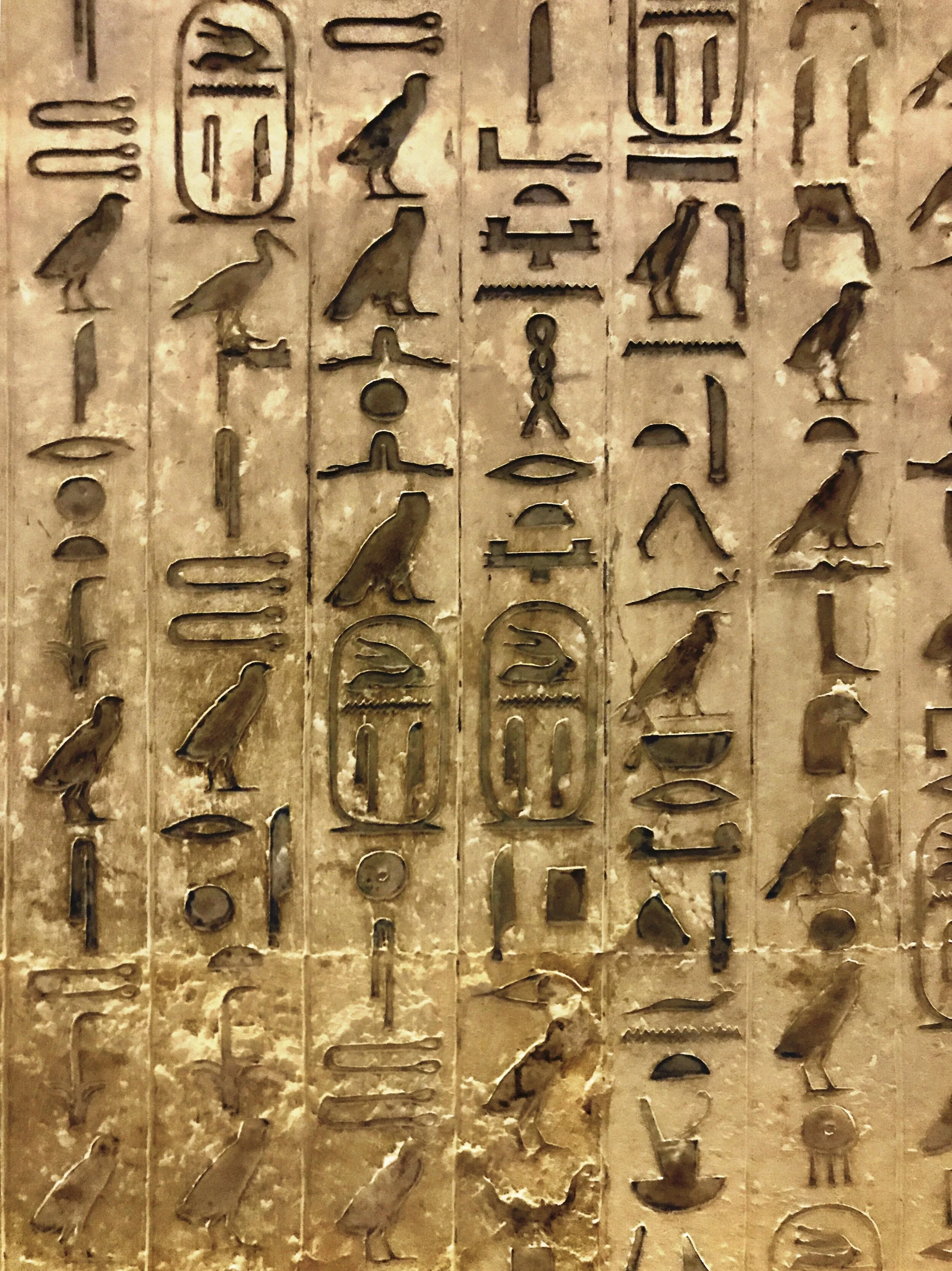

This dissent is evident in numerous carvings throughout Hatshepsut’s funerary temple. They read, “He who shall do her homage shall live. He who shall speak evil in blasphemy of Her Majesty shall die.”

That being said, “there is absolutely no evidence of insurrection, rebellion or coup during her reign,” Cooney points out. “Even if people were unhappy about Hatshepsut’s rule, they weren’t so dissatisfied that they were going to do anything about it.”

And why should they? All was right with the world during the two decades of Hatshepsut’s reign.

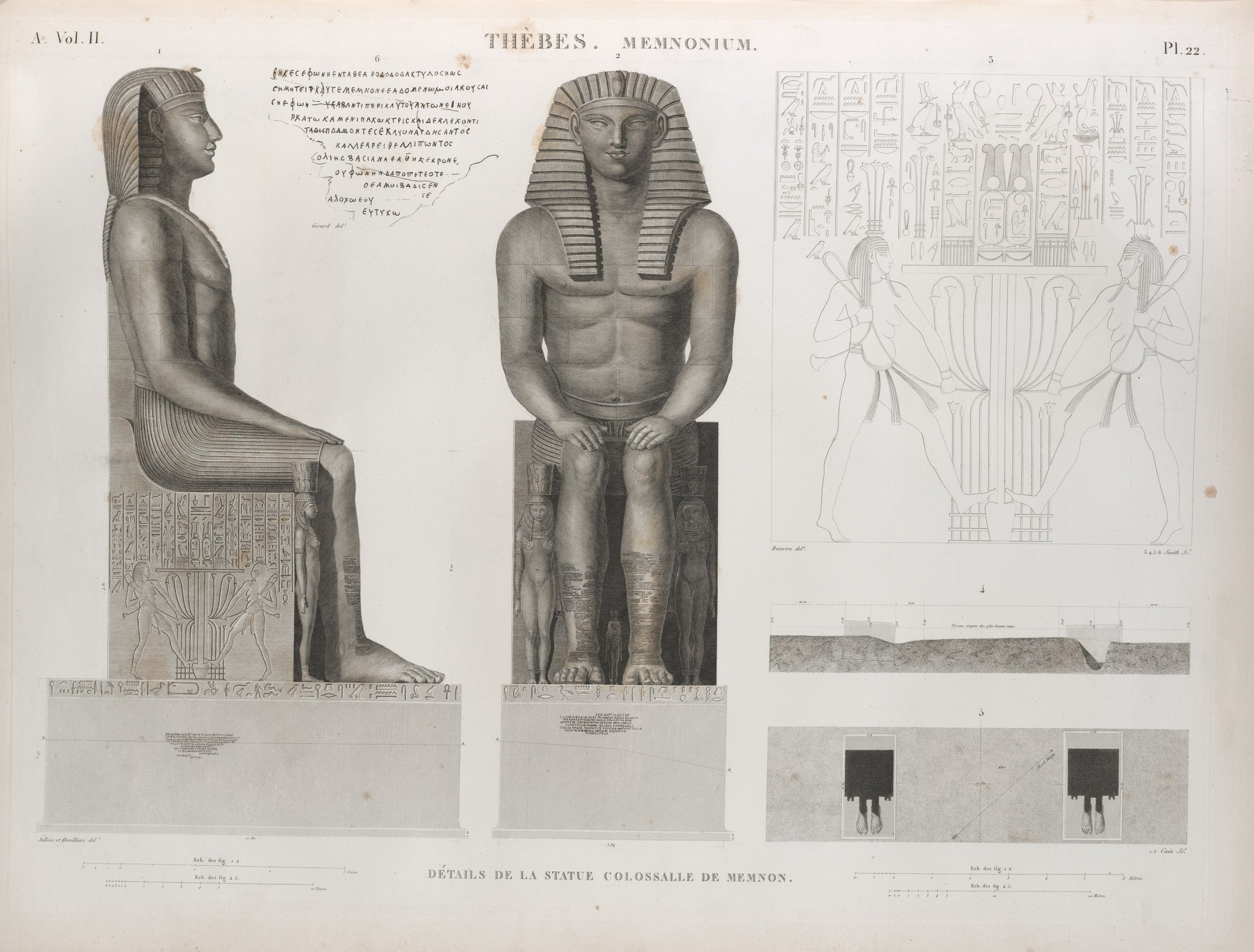

Riddle me this: Why did Thutmose III (seen here as a sphinx) wait so long for the smear campaign against his aunt and co-ruler?

Twenty-five years after Hatshepsut’s death, Thutmose III developed an obsession with erasing his co-pharaoh from history.

I suppose I should be grateful at how much of this amazing ancient culture is left to us. But I still get bummed at the gaps in what we know of its history. And one such gap is that we have no idea how Hatshepsut died. We do know that she reigned from about 1479 BCE until her death in 1458 BCE.

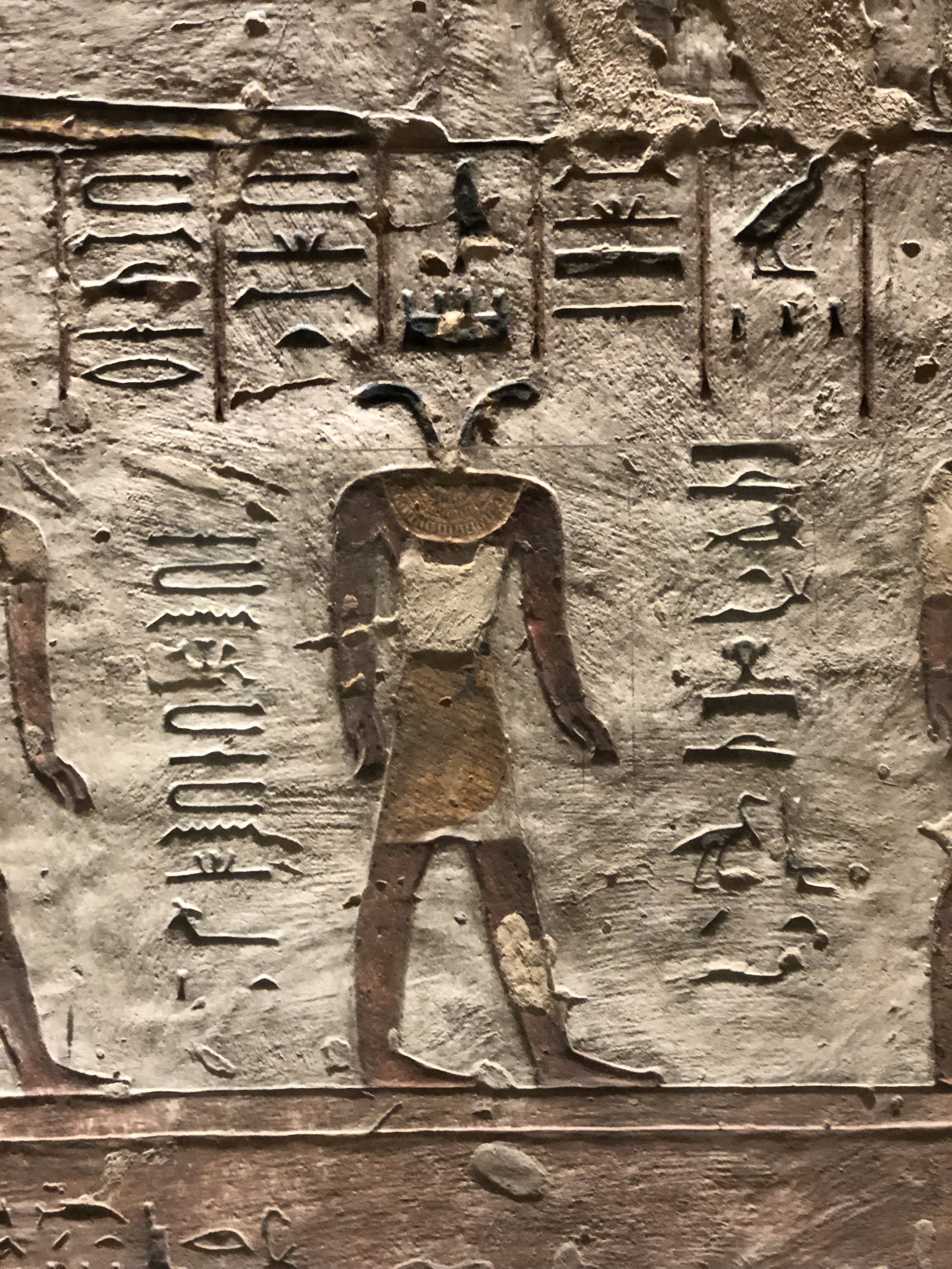

Thutmose III then became solo pharaoh. But it wasn’t until 25 years into his reign that he began a regime of obliterating all traces of Pharaoh Hatshepsut, starting with her impressive obelisks at Karnak (which were located at a prominent place where all could see). The masculinized depictions of Hatshepsut as king, after a bit of chisel work, were quickly reassigned to Thutmose II or Amenhotep I.

“It stands as our earliest evidence of Thutmose III’s removing Hatshepsut’s image from the temple landscape in favor of his own father’s,” Cooney writes. “But it was far from the last.”

Only the images of Hatshepsut as pharaoh were modified — those showing her as a queen were left untouched.

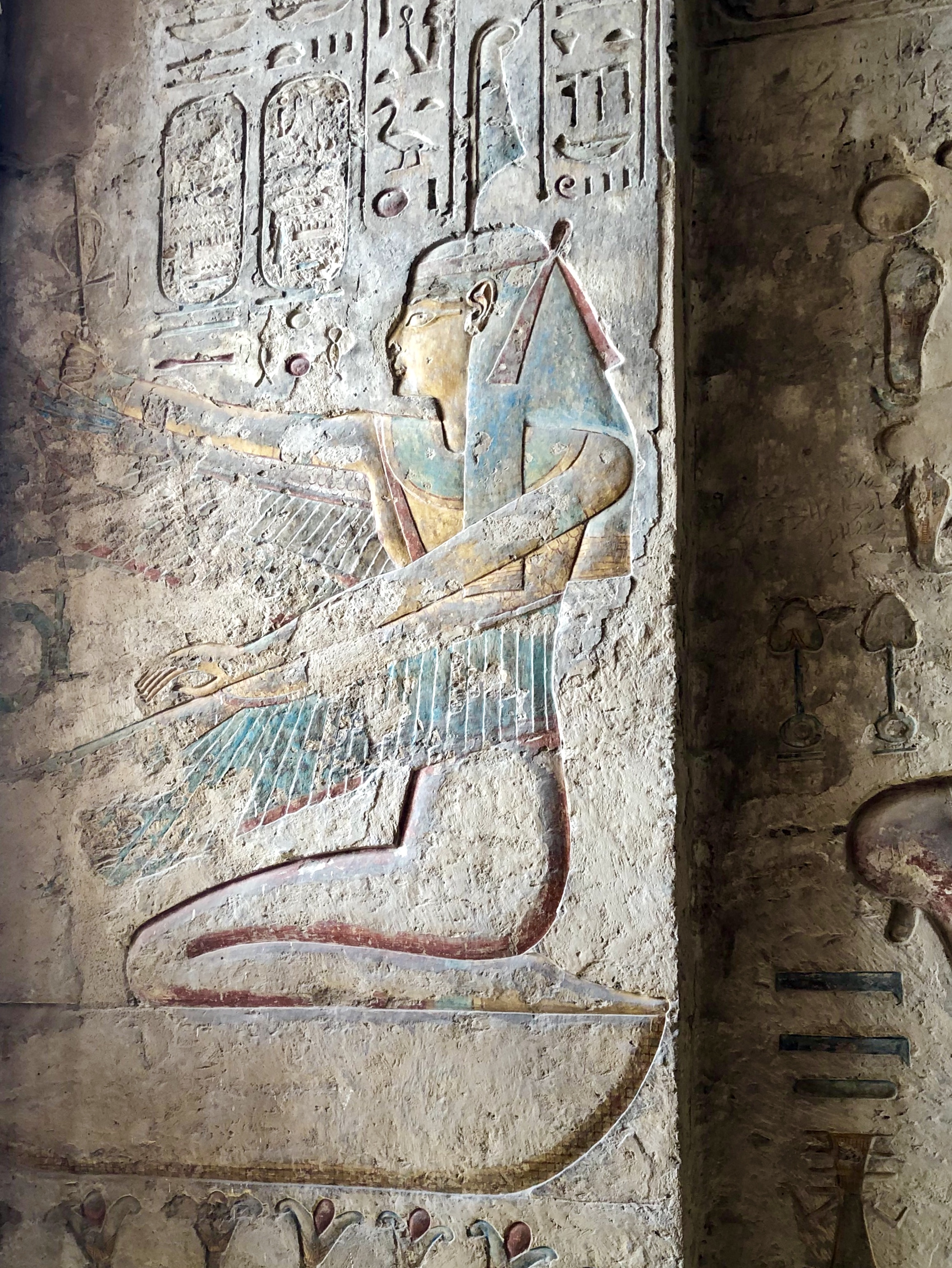

Thutmose III, shown in a devotional pose, must have asked the gods to secure the throne for his son

Thutmose III’s long-delayed plan to eradicate all evidence of Hatshepsut as pharaoh most likely was a way to secure the throne for his son.

Why did Thutmose delay for so long before deciding to obliterate Hatshepsut’s legacy? That’s when he was starting to concern himself with his successor. “Thutmose III waited until the end of his reign to systematically erase Hatshepsut’s presence because it was only then that he needed to shore up the legitimate kingship for a son who had no genealogical connection to Hatshpesut’s side of the family,” Cooney explains. “By removing his aunt, whose lofty and pure family connection sullied the aspirations of his own chosen son, Thutmose III was strengthening the history of his dynasty.”

Thank Amun, this smear campaign to eradicate the record of her rule ultimately wasn’t successful: “Despite the breadth and organization of the destruction, Hatshesut had simply built too much and embellished Egypt too wide for Thutmose III to destroy it all,” Cooney writes.

“Hatshepsut’s kingship was a fantastic and unbelievable aberration, but little more than a necessity of the moment,” Cooney wraps up. “Her feminine kingship was always to be perceived as a negative complication by the ancient Egyptians, a problem that could only be reconciled publicly and formally through its obliteration. After all her great accomplishments, despite her unique triumph, her fate was to be erased, expunged, silenced.”

I sure am glad that failed. Many references to Hatshepsut remained undisturbed. I’ve always been drawn to badass women, and Hatshepsut certainly qualifies. –Wally