Who the heck were Anubis, Osiris, Thoth and Amun? Learn about Egyptian deities and the crazy stories of Egyptian mythology.

As a kid, I loved mythology (still do) — but I hated how many different versions there were of every tale. Couldn’t they all just agree upon one story and stick with it?

Of course, now, as an adult, I realize things aren’t that simple. Deities begin as one thing and evolve into something else. They get conflated with other gods. Their worship extends to a new region, where they take on new aspects.

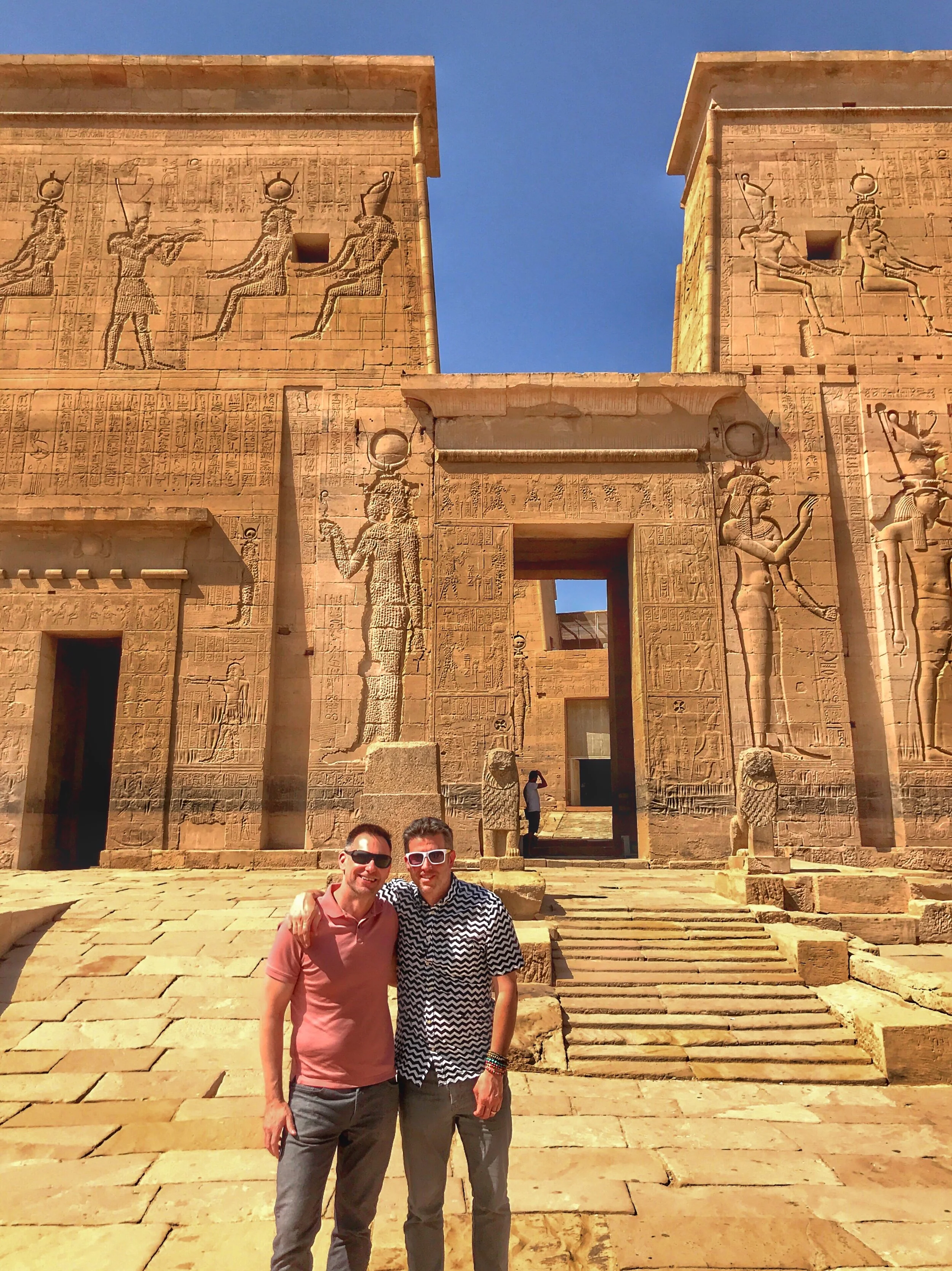

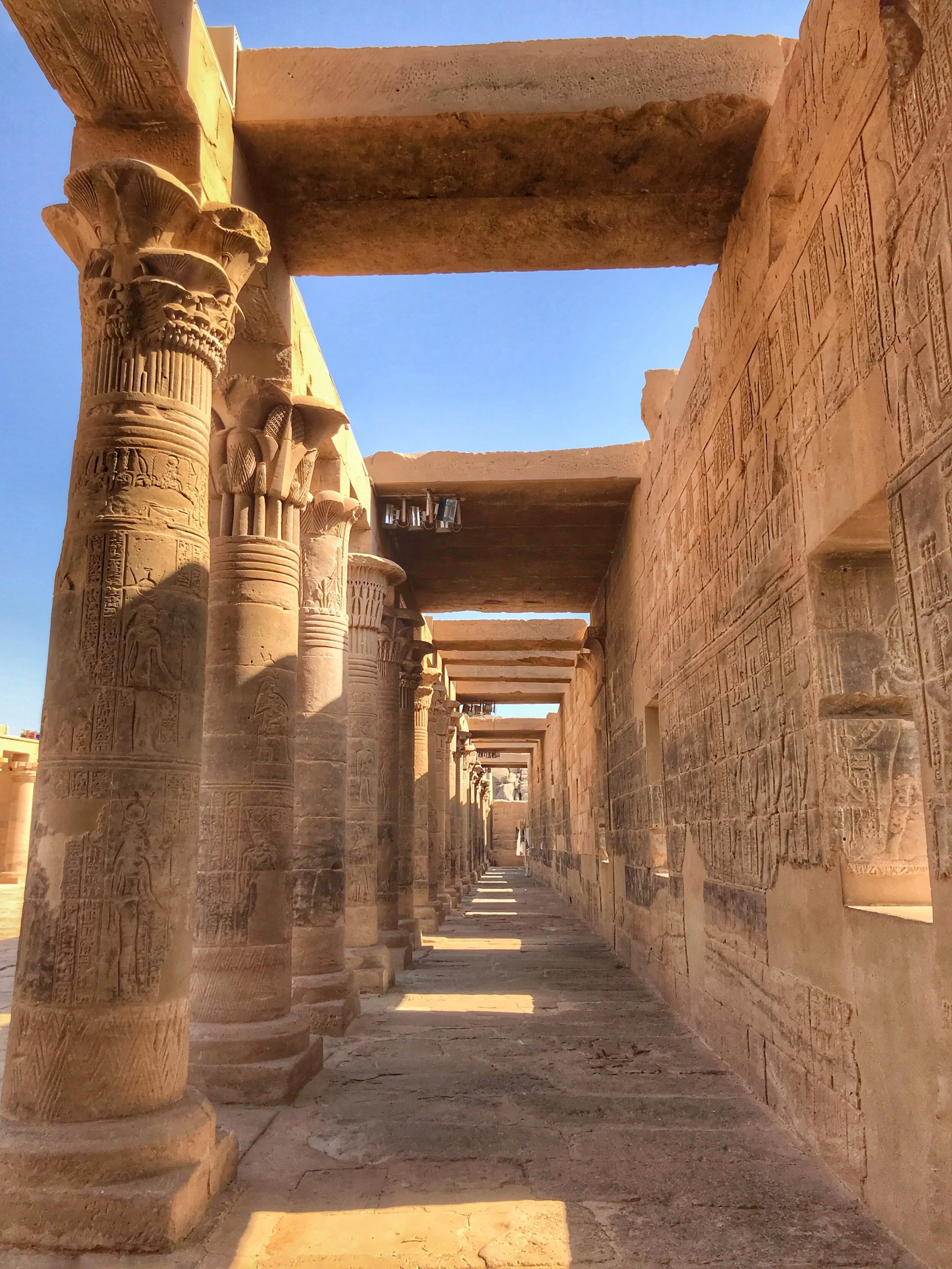

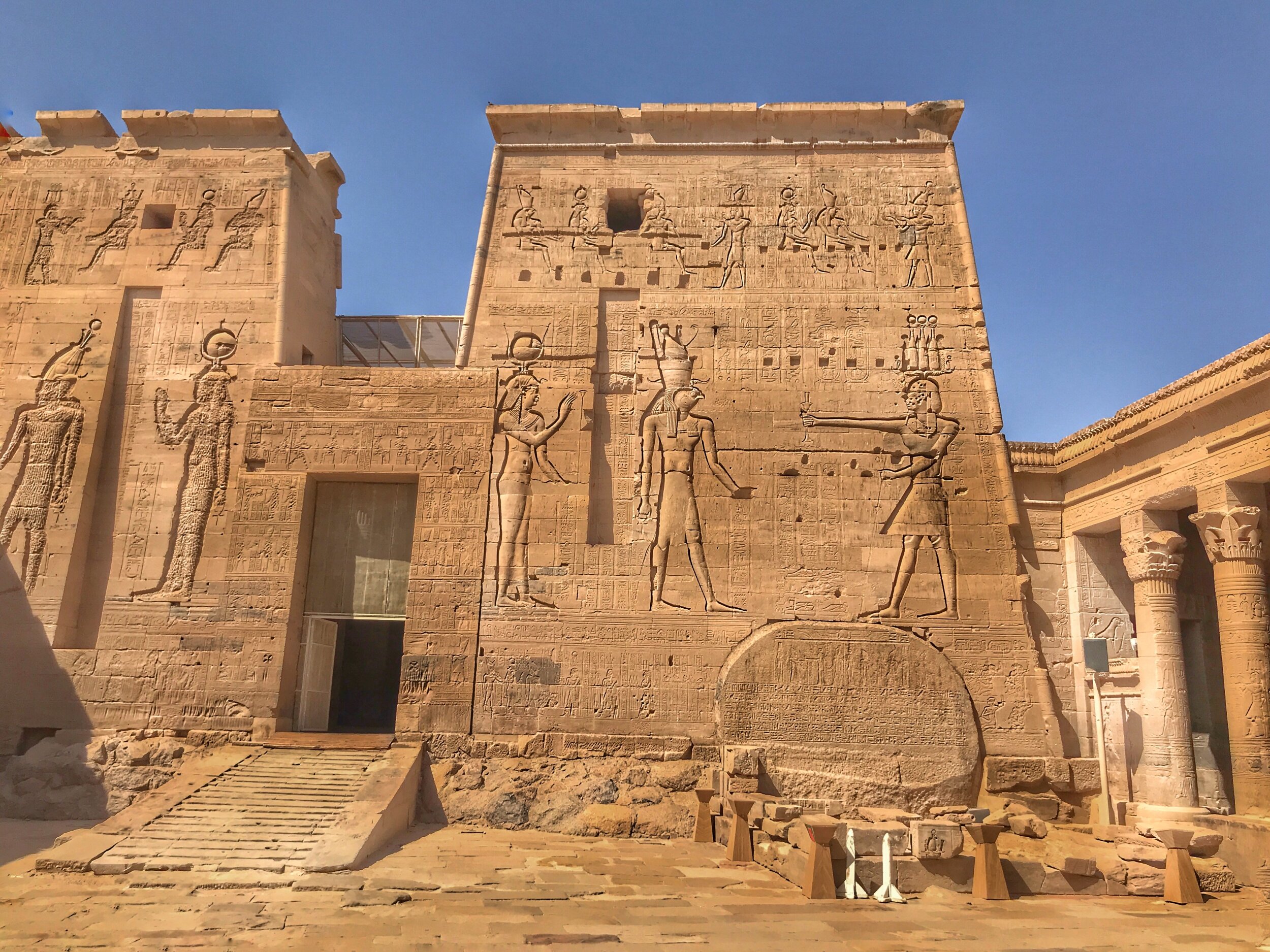

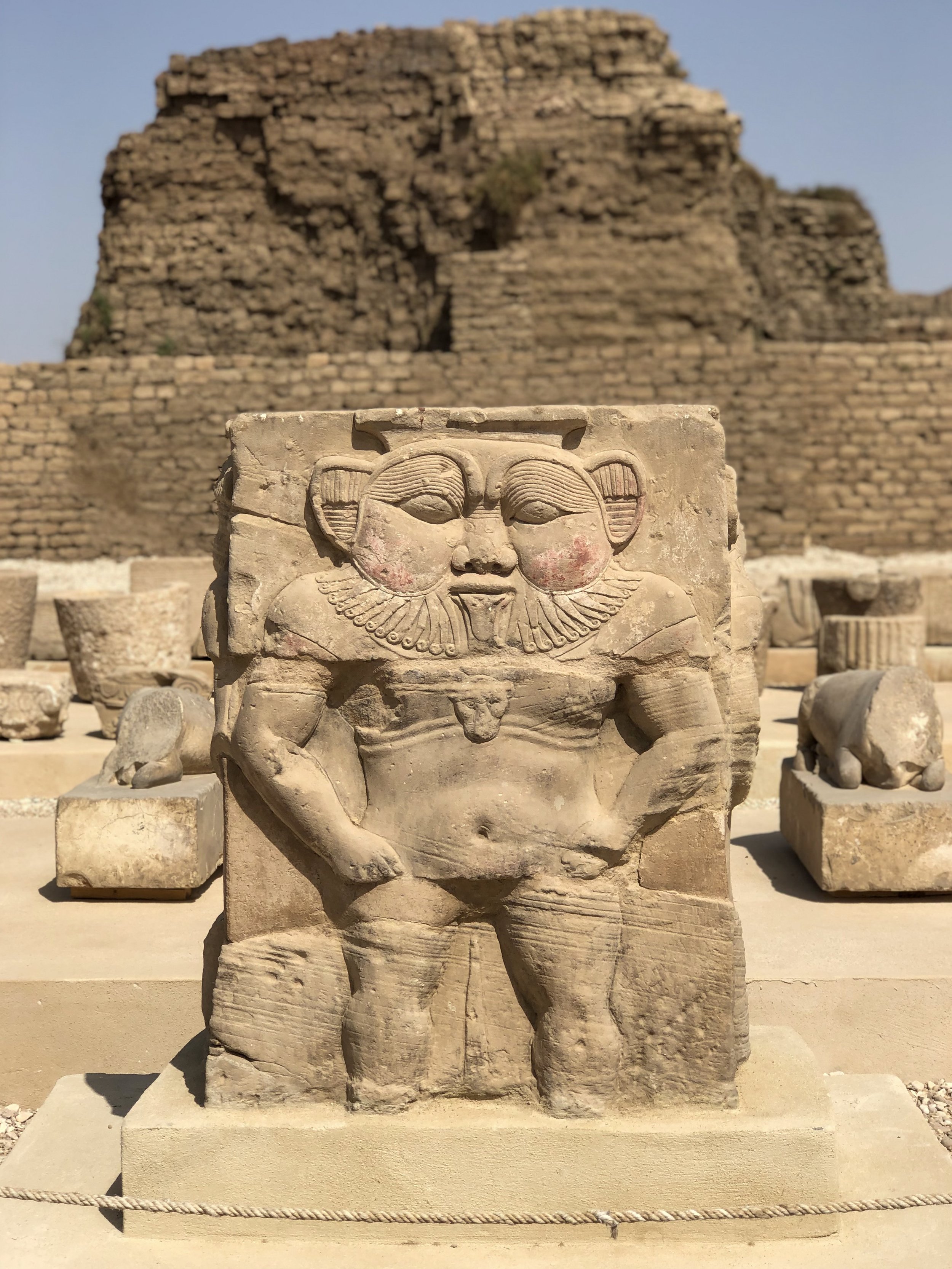

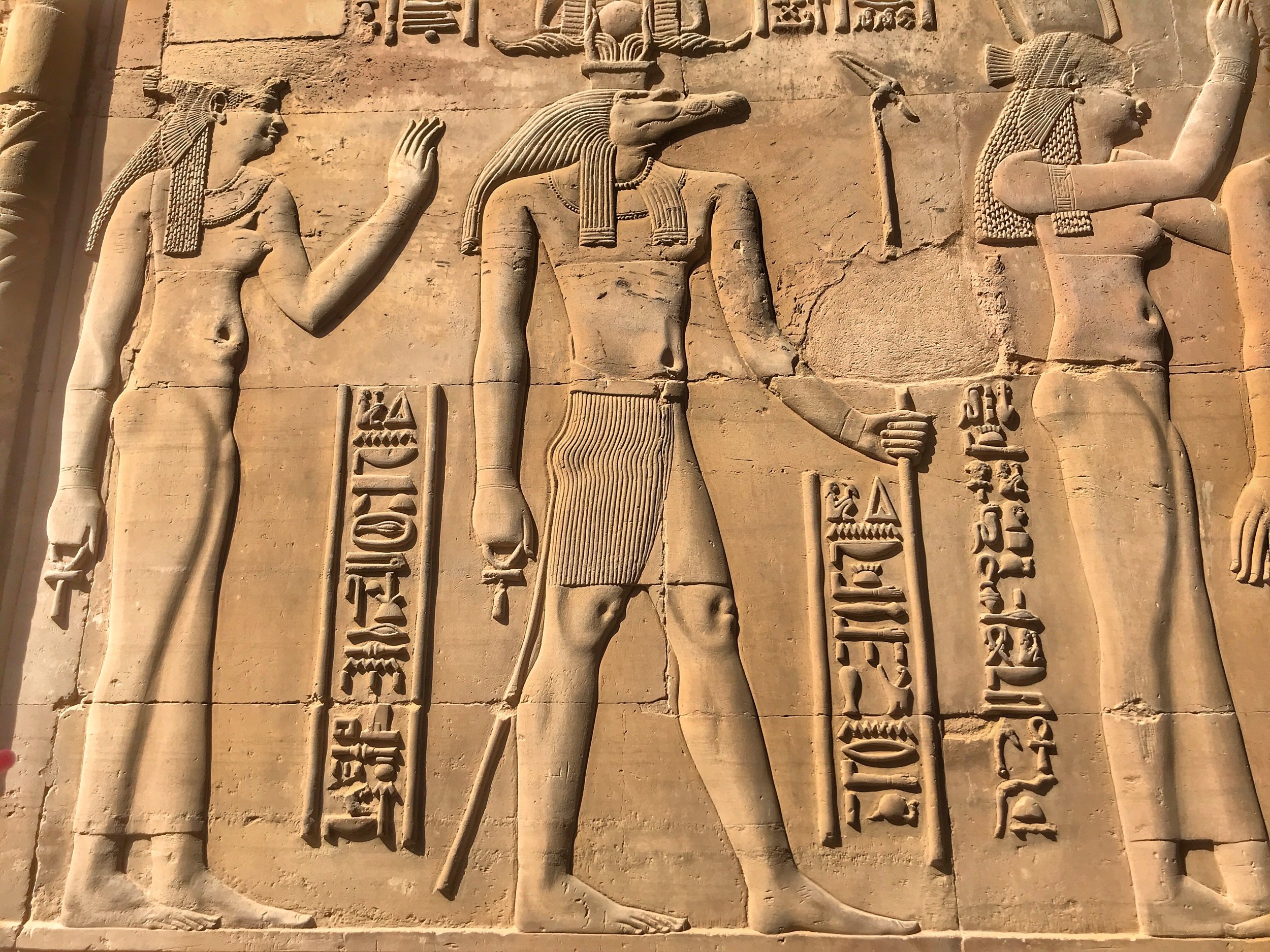

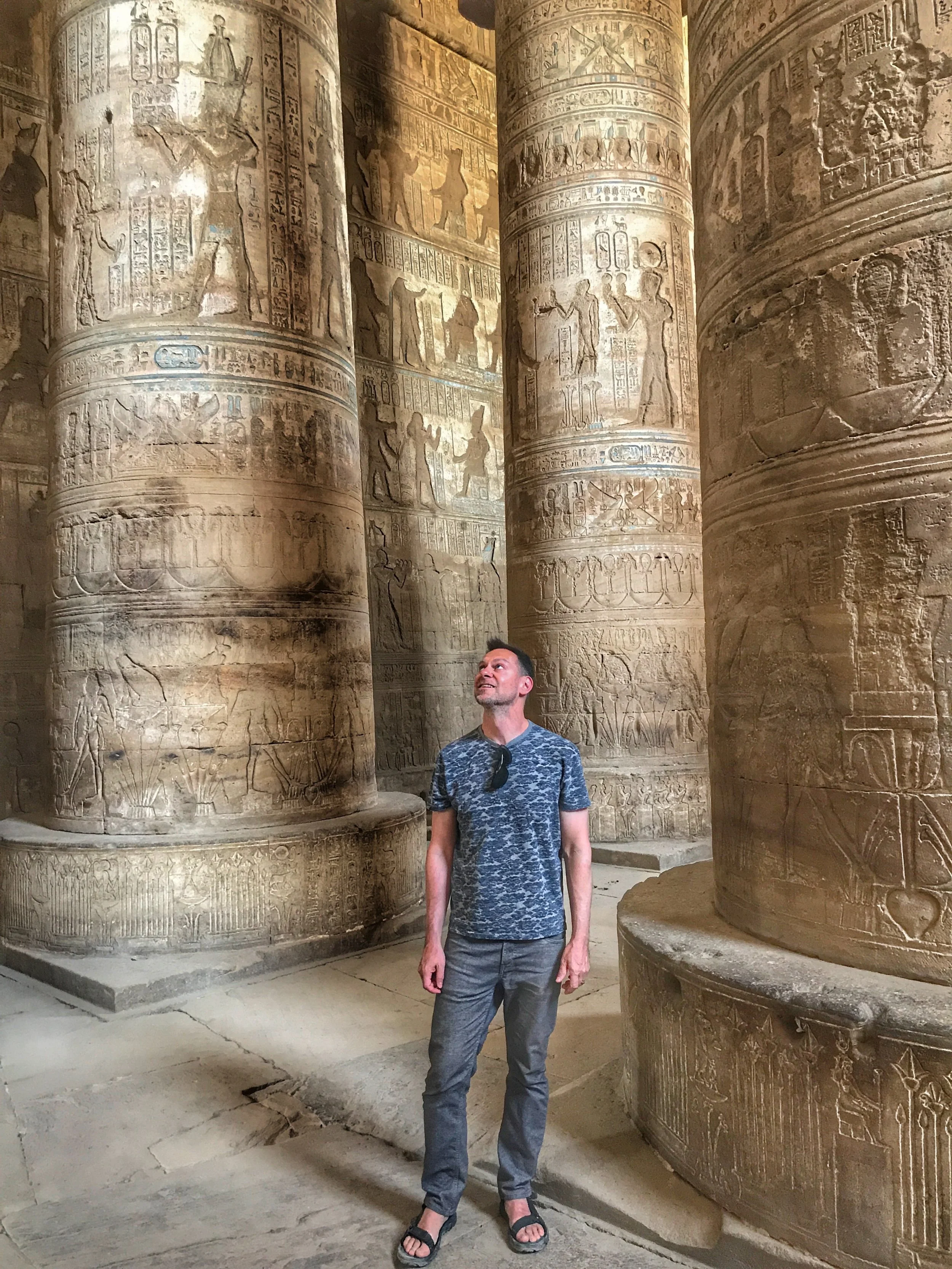

If you’re planning a trip to see the wonders of Egypt, it’s helpful to know a bit about the gods and goddesses beforehand. Temple carvings can blur together after a while, so it’s more fun to be able to spot the deities in the images: Hey! I know that green-skinned mummy-looking dude! That’s Osiris, lord of the afterlife!

Here’s a primer on this often-bizarre pantheon, mostly culled from The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt by Richard H. Wilkinson. (And be sure to check out our glossary of the lesser-known Ancient Egyptian gods, too!)

Amun

Aka: Amon, Amen, Amun-Re

Domain: The sun and fertility. As the supreme god of the Egyptian pantheon, he’s also credited in some tales for thinking the world into being.

Description: A human male, often with the head of a ram

Consort: Mut

Strange story: A young daughter of the reigning pharaoh was given the role of divine wife of Amun. Her duties including rubbing the phallus of the god’s statue until she felt it “orgasm.”

Anubis

Domain: Mummification, death and the afterlife

Description: A man with a black jackal head

Strange story: Anubis mostly likely got this head because desert canines would scavenge the shallow graves in early cemeteries, and people sought protection from the very creature that would threaten their eternal peace.

Bastet

Aka: Bast

Domain: Cats and pregnancy

Description: A woman with the head of a cat, or simply a cat itself

Strange story: Entire cemeteries at Saqqara and elsewhere are filled with cat mummies killed as offerings to the goddess.

Hathor

Domain: Women, female sexuality and motherhood, as well as music and happiness

Description: A woman with bovine features, usually cow ears, as can be seen atop Hathor columns. Sometimes depicted as a cow or a woman wearing a vulture cap.

Consort: Hathor is, alternately, the mother and wife of Horus.

Strange story: One of her nicknames is Mistress of the Vagina. When the sun god Re was depressed, Hathor flashed her pussy at him. It did the trick: Re laughed and rejoined his fellow gods.

Horus

Aka: Re-Horakhty

Domain: The sky, sun and kingship

Description: A falcon-headed man or infant

Strange story: During an epic battle with his Uncle Seth, Horus climbed a mountain with his mother Isis’ decapitated head. He fell asleep, and Seth snuck up and gouged out Horus’ eyes and buried them. Lotuses sprouted from the eyes, and the goddess Hathor restored Horus’ sight by pouring gazelle milk over the sockets.

Isis

Domain: The cosmos, magic, mourning and the dead

Description: A woman with large horns and the solar disc atop her head, sometimes with wings

Consort: She’s the sister and wife of Osiris, with whom she had Horus.

Strange story: A popular way to depict Isis was to show her breastfeeding Horus. Because pharaohs were the living incarnation of Horus, Egyptian kings were said to drink Isis’ breast milk as well.

Maat

Aka: Ma’at

Domain: Truth, justice and the cosmic order

Description: A woman with a bird’s tail feather atop her head, sometimes shown with wings under her arms

Consort: Thoth

Strange story: Upon death, the heart was placed upon a scale. If it weighed less or the same as the feather of Maat, the person had led a virtuous life and could go on to the afterlife. If not, they’d be devoured by the demoness Ammit, who was part lion, hippo and crocodile.

Mut

Domain: Motherhood

Description: Early depictions show her with the head of a lioness, but she’s most often shown as a woman in a feathered dress wearing either the White Crown of Upper Egypt or the Double Crown of the Two Lands.

Consort: Amun

Strange story: Mut was sometimes shown with an erection and three heads — those of a vulture, lion and human. In this aspect, she was said to be “mightier than the gods.”

Osiris

Domain: Ruling over death, resurrection and fertility, he’s the lord of the underworld.

Description: A green mummy holding the crook and flail, symbols of Egyptian royalty, and wearing the atef crown, a white bowling pin-like headpiece flanked by two tall feathers

Consort: Isis

Strange story: His jealous brother Seth murdered him and chopped him into pieces, hiding the body parts all over Egypt. Osiris’ dutiful wife, Isis, hunted down and found all the pieces, save one: his pecker.

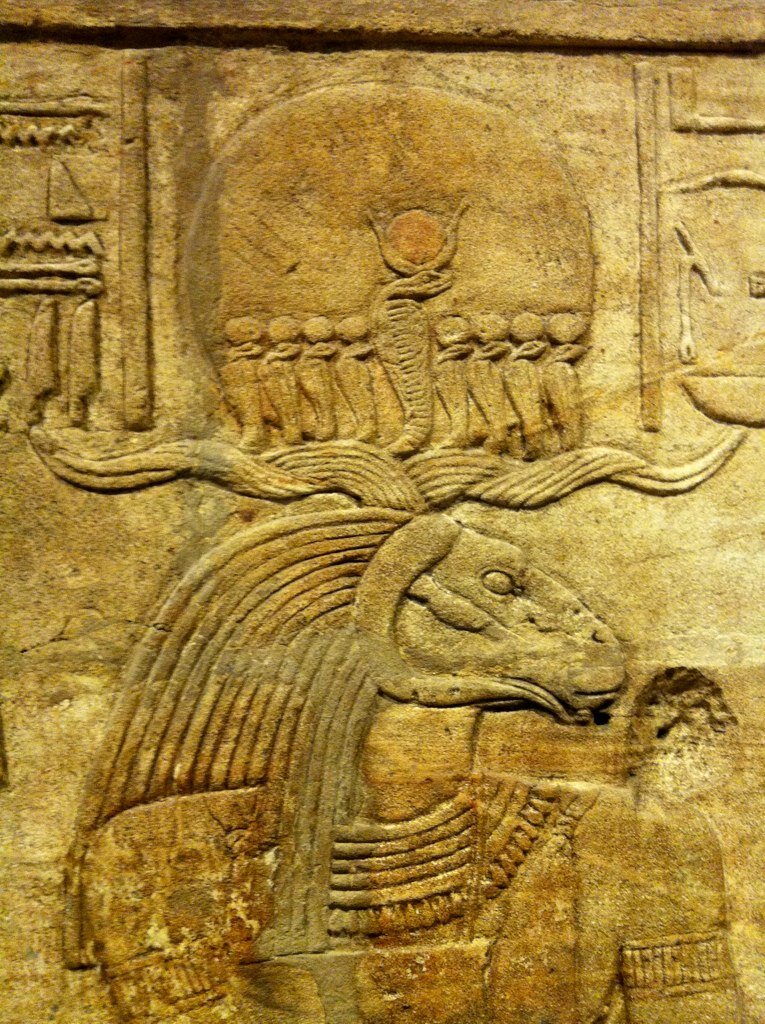

Re

Aka: Ra (though he merged with many other deities as well, including Amun and Horus)

Domain: The sun

Description: The sun, encircled by a cobra, sometimes with wings. He has a falcon head in his Re-Horakhty version.

Strange story: In one myth, Re created the world. When he “cut” his cock, possibly a reference to circumcision, two deities sprang from the drops of blood: Hu (Authority) and Sia (Mind).

Seth

Aka: Set

Domain: Violence, chaos, confusion, cunning and storms

Description: A man with a long tail and a strange curved animal head that has tall, squared-off ears

Strange story: He molested his nephew Horus but then lost the throne of Egypt when he unwittingly ate lettuce that had Horus’ jizz on it.

Thoth

Domain: Knowledge and the moon

Description: A man with the head of an ibis, a now-extinct bird with a long, thin, curved beak. Sometimes also shown as a baboon

Strange story: Thoth invented writing and is the Lord of Time, recording history. Scribes would pour out a drop of water for him from their brush pot as a libation at the beginning of each day. –Wally