The Old Cataract, now owned the French Sofitel hotel group, sits along the banks of a lazy stretch of the River Nile in the southernmost tip of Egypt

Nothing short of an Arabian fantasy, this historic luxury hotel is the perfect place to stay in Aswan for a day trip to Abu Simbel. If it’s good enough for Agatha Christie, it’s good enough for us.

If that looks like a long walk to the hotel’s entrance don’t worry! A golf cart will take you

After a brief flight from Cairo to Aswan, Wally and I exited the airport and met our pre-arranged driver. We were dropped off at the main gatehouse of the Sofitel Legend Old Cataract and transported by a golf cart through the well-manicured courtyard to the hotel’s impressive Victorian-era façade. We followed a porter through the grand Moorish Revival lobby to a soft velvet sofa, where we were served complimentary champagne flutes of cool hibiscus tea.

I looked over at Wally. He was grinning from ear to ear.

“The Old Cataract Hotel isn’t a time machine exactly, but it was definitely a relaxing departure from ordinary 21st century life. ”

It was love at first sight for Wally

We were greeted with a flute of chilled hibiscus tea

We chose the hotel as it’s ideally situated near the Philae Temple and a base for the three-hour drive to Abu Simbel. And it's not everyday that you get the chance to stay at a landmark pedigreed property once occupied by Dame Agatha Christie herself.

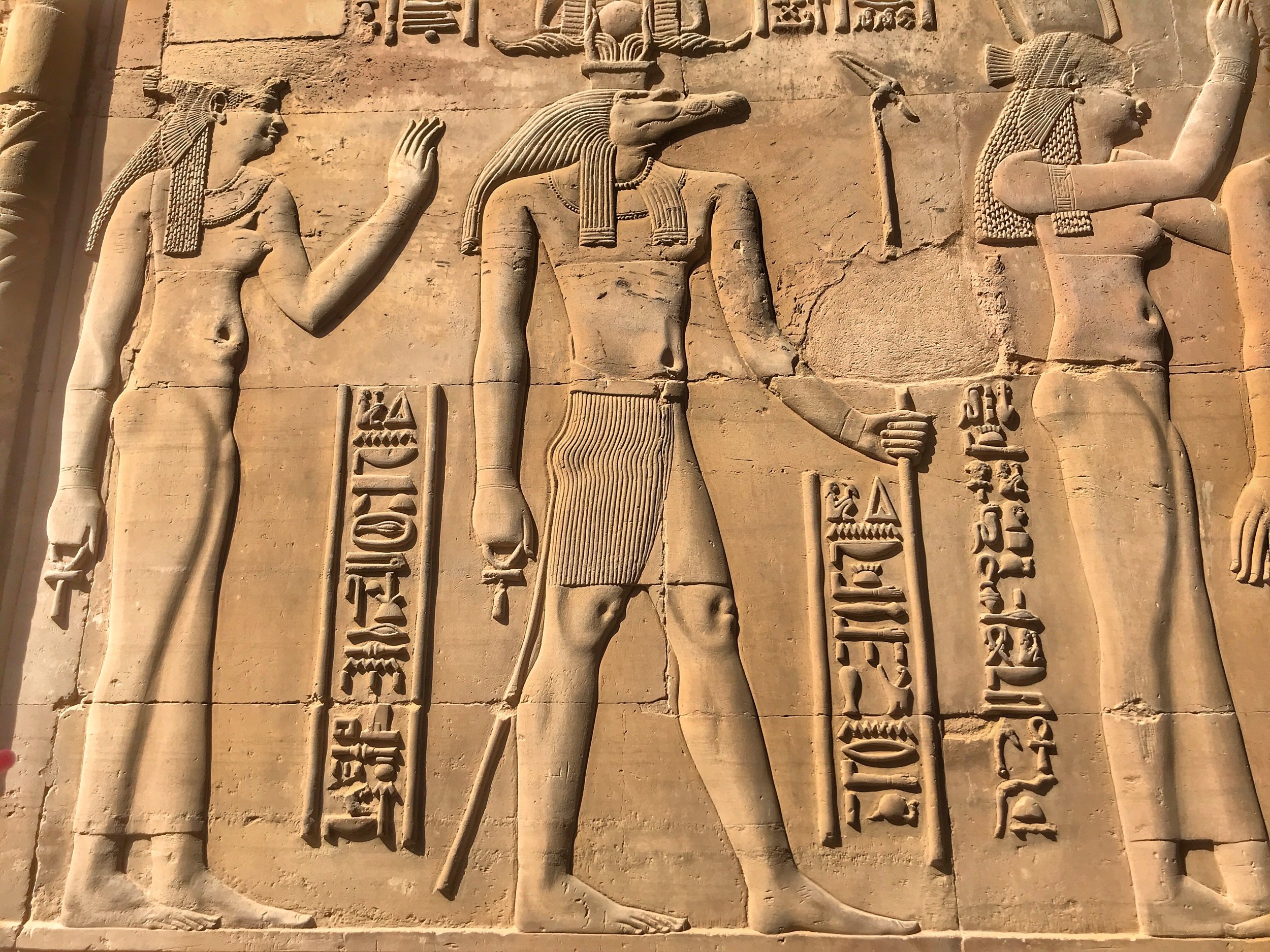

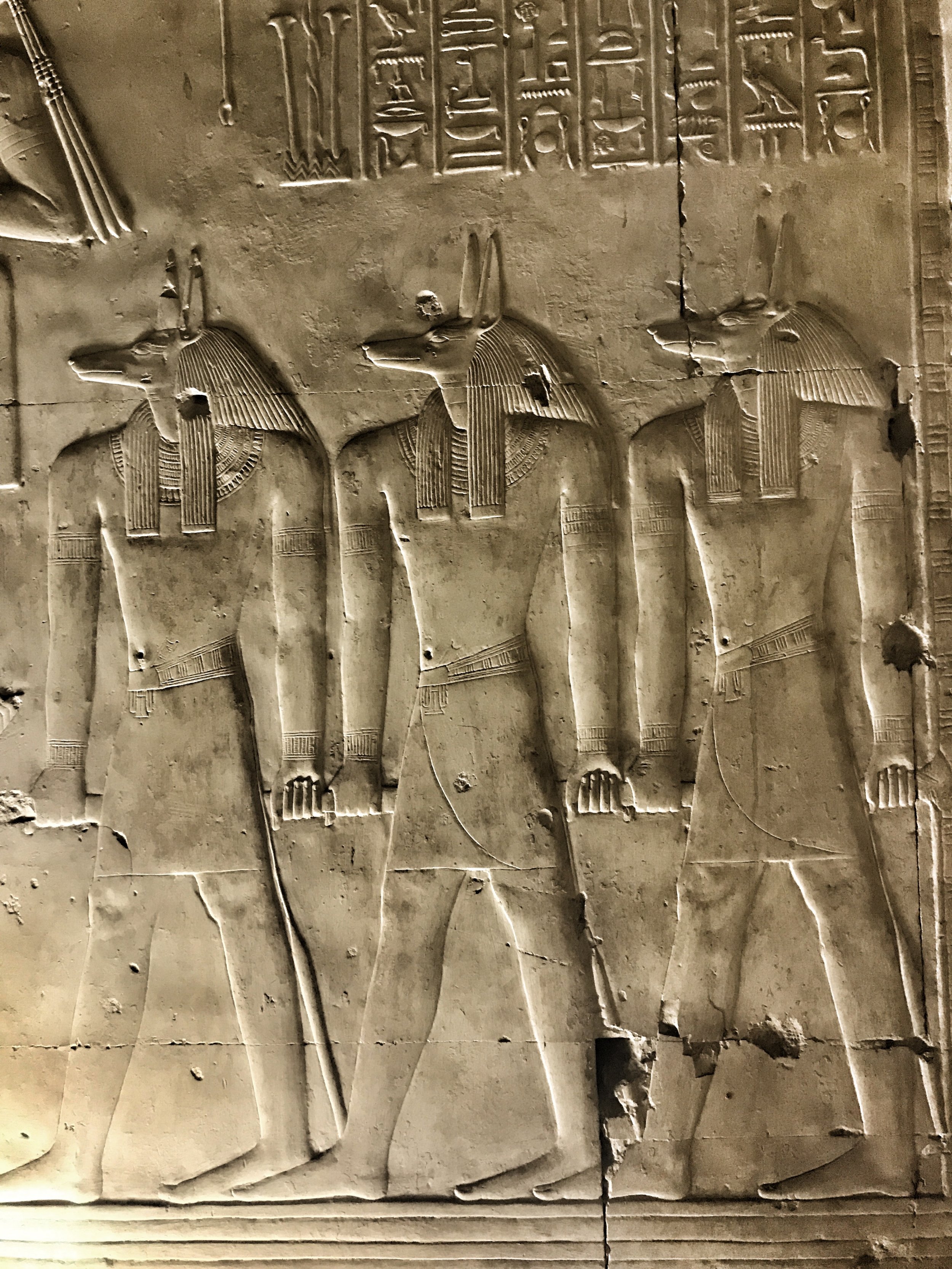

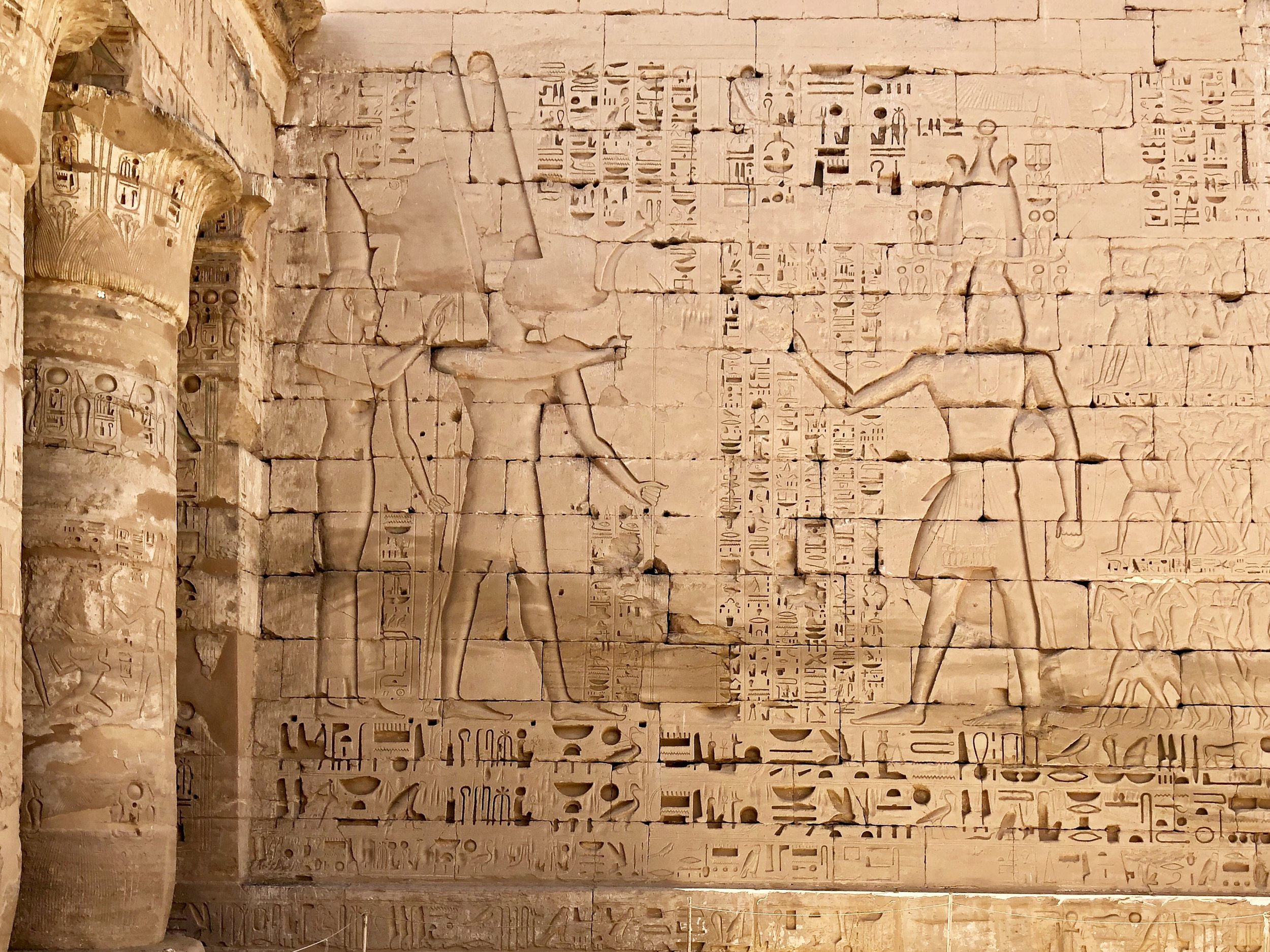

Created by architect Henri Favarger at the turn of the century and financed by British entrepreneur Thomas Cook, the Old Cataract Hotel perches upon an undulating pink granite bluff overlooking a lazy stretch of the Nile and Elephantine Island. From the hotel, guests can admire the columns of a small restored temple on the island dedicated to the goddess Satis. She was the consort of the creator god Khunm, a protector of the southernmost frontier of Egypt and closely associated with the annual Nile inundation.

The Palace Wing of the hotel

Join the likes of Lady Diana and Winston Churchill and stay at the Old Cataract in Aswan

The hotel got its name from its proximity to the first cataract, or branch, of the Nile, where the river narrows and granite outcrops rise above the water, separating Egypt and Nubia. Ancient Egyptians believed that this marked the source of the sacred river and was where the civilized world reached its end.

Agatha Christie was here — in fact, she wrote parts of Death on the Nile in this suite

Take a Tour: The Agatha Christie Suite and More

The iconic property is managed by the French luxury hotel group Accor and offers a daily walking tour where you can learn a bit about its storied past as a favorite escape for its prominent guests. During the tour, we saw the Agatha Christie suite, where the mystery novelist stayed for months in 1937, immortalized in her novel Death on the Nile. Scenes from the 1978 film adaptation were filmed here. The suite, now set up as a shrine of sorts, includes a private balcony with river views, fireplace, separate living room, bedroom and dining room.

This painting hangs in the Agatha Christie suite at the Old Cataract. You, too, can stay there for a mere $8,000 a night!

A collection of framed photographs of royals, writers, politicians and other luminaries who have stayed at the Old Cataract adorn the hallway walls.

Formal dress is required to dine in 1902, the Old Cataract’s upscale restaurant

Also included was a visit to 1902, the hotel’s elegant fine dining restaurant. The architecture, with vaulted ceilings, a dome and Moorish arches, was inspired by the Mamluk mosques of Cairo. Our guide informed us that if you wanted to dine here, formal dress is required.

These colorful arches frame the indoor restaurant, where the breakfast buffet is served

In 2011, the hotel reopened after a three-year closure for a complete renovation led by French interior designer Sybille de Margerie. It was the third property to receive the Legend designation, signifying historical properties that have been updated with Sofitel's trademark French touch.

The property is divided into two buildings, separated by a large outdoor swimming pool: the historical Palace Wing with its Moorish striped horseshoe arches and the contemporary Nile Wing.

We stayed in the newer wing of the hotel

The Nile Wing

We stayed in the nine-story Nile Wing, built in 1961, a bit of a misnomer as it’s actually a hotel in its own right. Decorative patterns and light fixtures from the original structure have been faithfully reproduced here and act as a stylistic bridge between the two buildings.

Our Nile view suite was spacious, with a sitting area, king-size bed and private balcony with a panoramic view of the pool and Nile. The bathroom was luxurious, with a freestanding bathtub, walk-in shower and separate closet for the toilet and bidet, plus plenty of towels and a pair of terry cloth robes.

Our bed, with the sitting area beyond

Bathe in the tub or the shower stall next to it

The ruins of Elephantine Island could be seen from our balcony

Wally hung out on the balcony a lot — you just can’t beat that view!

One evening, just before twilight, Wally and I walked down to the jetty on the hotel grounds, where guests can take a felucca sailboat on the Nile. The unforgettable and magical ride on the waters of the sacred river was one of the highlights of our trip.

Returning to our suite after our felucca ride the first evening, we caught a glimpse of the opulent indoor pool located just beyond the lobby of the Nile Wing in the hotel spa. We stopped to take a closer look and came upon a British couple frolicking, the man giddy with excitement at having the pool all to themselves. The following evening, we followed their lead, reveling in this gorgeous setting, pleased to find the water much warmer than that of the outdoor pool.

Duke before he and Wally hired some local sailors to take them out for a peaceful felucca ride along the Nile at sunset

The Nile Wing’s pool is warm, and there’s a good chance you’ll have it all to yourself

The hotel has a total of four dining venues, though we ate all of our meals on the terrace. The impressive breakfast buffet includes a chef station, where you can order à la carte. Room service is also available and was especially convenient when we had a lavish feast delivered before our 5 a.m. departure to Abu Simbel.

The bar at the Old Cataract

We ate our meals on the veranda, sometimes joined by a timid but hungry stray cat

The Oriental Kebabgy restaurant at one end of the Nile Wing

While staying at the hotel I experienced what I dubbed “mummy tummy,” which was possibly a minor case of heatstroke. I hadn’t realized how hot it was at these exposed sites and didn’t drink enough water. Our travel guide Rasha suggested I take Antinal, as we had somehow forgotten to bring Imodium with us. A quick call to the front desk, and within half an hour, the medication was hand-delivered to our suite.

The evening before our departure, the concierge called to ask if there was anything they could improve upon. Wally replied that it would be nice if they had an ATM on site and was told that there’s one in the guest services house out by the hotel gate. “Then there’s nothing you can do to improve,” Wally replied, smiling.

Leaving our room for the last time, I glanced over the palm trees and across the river at the Aga Khan Mausoleum. Neither of us wanted to leave this idyllic setting. The Old Cataract Hotel isn’t a time machine exactly, but it was definitely a relaxing departure from ordinary 21st century life. –Duke

Add Aswan to your agenda to see Abu Simbel and Philae Temple. Of course, you have to stay at the legendary Old Cataract. You’ll never want to leave

Sofitel Legend Old Cataract Hotel Aswan

Abtal El Tahrir St.

81511 Aswan

Egypt