Explore the hidden world of fairies — from pixies and brownies to elves and gnomes. Discover why these mysterious beings captivate imaginations … and what secrets lie just beyond the mortal realm.

The Seelie Queen on her thornwood throne

There are places in this world where the veil between realms grows thin: a lonely stretch of moorland, a glade deep in the woods, a ring of mushrooms.

But beware, for the Fae are not the charming, glitter-winged sprites of modern fairy tales. They’re older than memory, creatures of wild magic, bound to no human morality. They can bless you with impossible luck or curse you with misfortune that lingers for generations. Some are beautiful beyond compare — slender and radiant, with eyes like moonlit pools. Others are twisted things, hunched and sharp-toothed, watching from the shadows.

To stumble upon the Fae is to risk losing yourself. Accept their gifts, and you may find they come at a terrible price. Eat their food, and you may never leave their world. Speak too freely, and they may steal your name, your shadow or your very soul. And if you are very unlucky or unwise — if the music lures you in, if the golden-haired stranger takes your hand — you may wake to find a hundred years have passed while you danced, and everyone you once knew is dust.

Yet still, we seek them out. We leave out offerings of milk and honey at Beltane, Litha and Samhain, whisper our wishes into the wind, and step just a little too close to the edge of the veil, hoping for a glimpse of something otherworldly.

Across the globe, countless myths and legends speak of these elusive beings, each culture shaping its own version of the Fae. Some are noble, some monstrous, some little more than a trick of the light. But one truth remains: The Fae are watching. And if you’re not careful, they may just take notice of you.

Fairy Folklore Around the World

In different cultures, stories of the Fae take many forms — some enchanting, some terrifying, all captivating. Whether they’re the luminous Sidhe of Ireland, the cunning yōkai of Japan, or the water-dwelling rusalki of Slavic lore, fairies defy easy categorization. They’re both protectors and tricksters, wise beings and dangerous predators, granting favors with one hand and snatching them away with the other.

Let’s step into the shadowy glens and moonlit crossroads where the Fae linger, exploring how different cultures have imagined these otherworldly creatures — and where you might still find traces of them today.

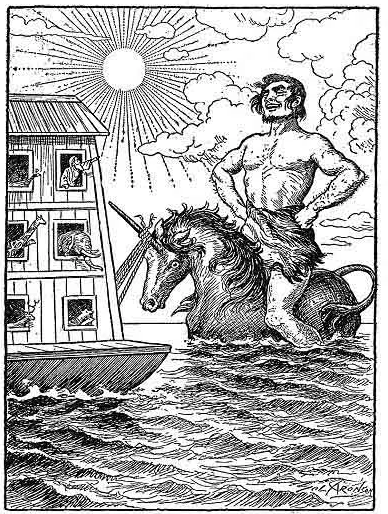

The Tuatha Dé Danann, or Sidhe, riding their spectral horses

The Tuatha Dé Danann and Irish Fairies

Beneath the rolling green hills of Ireland, hidden within ancient mounds and hollowed-out trees, dwell the Sidhe (pronounced “Shee”), the Shining Ones. These are no fluttering pixies, but tall, radiant beings, their beauty almost painful to behold. Clad in shimmering garments, their eyes hold the weight of centuries, and their voices carry the echoes of forgotten songs.

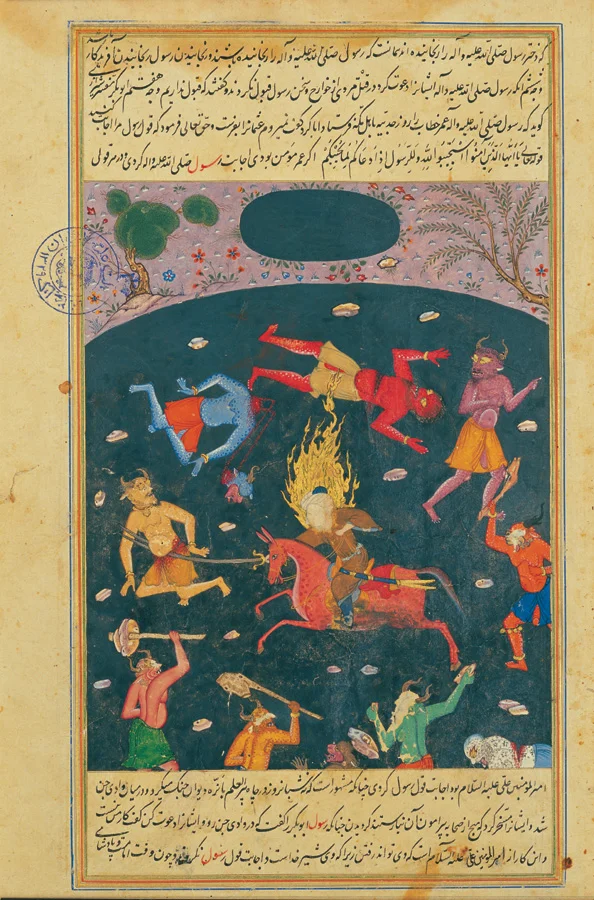

The Tuatha Dé Danann, Ireland’s old gods, were said to have retreated into the earth after their defeat, becoming the Sidhe of legend. They ride out on spectral horses, sweeping mortals away in a fever dream of music and revelry. Some who enter their world return, forever changed; others vanish without a trace.

Not all Irish fairies are so regal. The púca, a shapeshifter, appears as a sleek black horse with burning eyes, a rabbit, or even a goblin-like creature with long fingers and an unsettling grin.

The banshee, with her silver hair and wailing cries, is a harbinger of death, while changelings — sickly, eerie children left in place of stolen human babies — are a reminder of the Fae’s more sinister tendencies.

A banshee’s wail means someone you love is about to die.

Irish Fae in Popular Tales

The Stolen Child by W.B. Yeats captures the allure of the fairies, calling children away to a land of “waters and the wild.”

In The Call by Peadar Ó Guilín, modern teenagers are abducted into the Grey Land of the Sidhe, where they must survive deadly hunts.

Jonathan Strange & Mr Norrell by Susanna Clarke presents a version of the Fae as manipulative and powerful, with the Gentleman with the Thistledown Hair embodying their eerie and unpredictable nature.

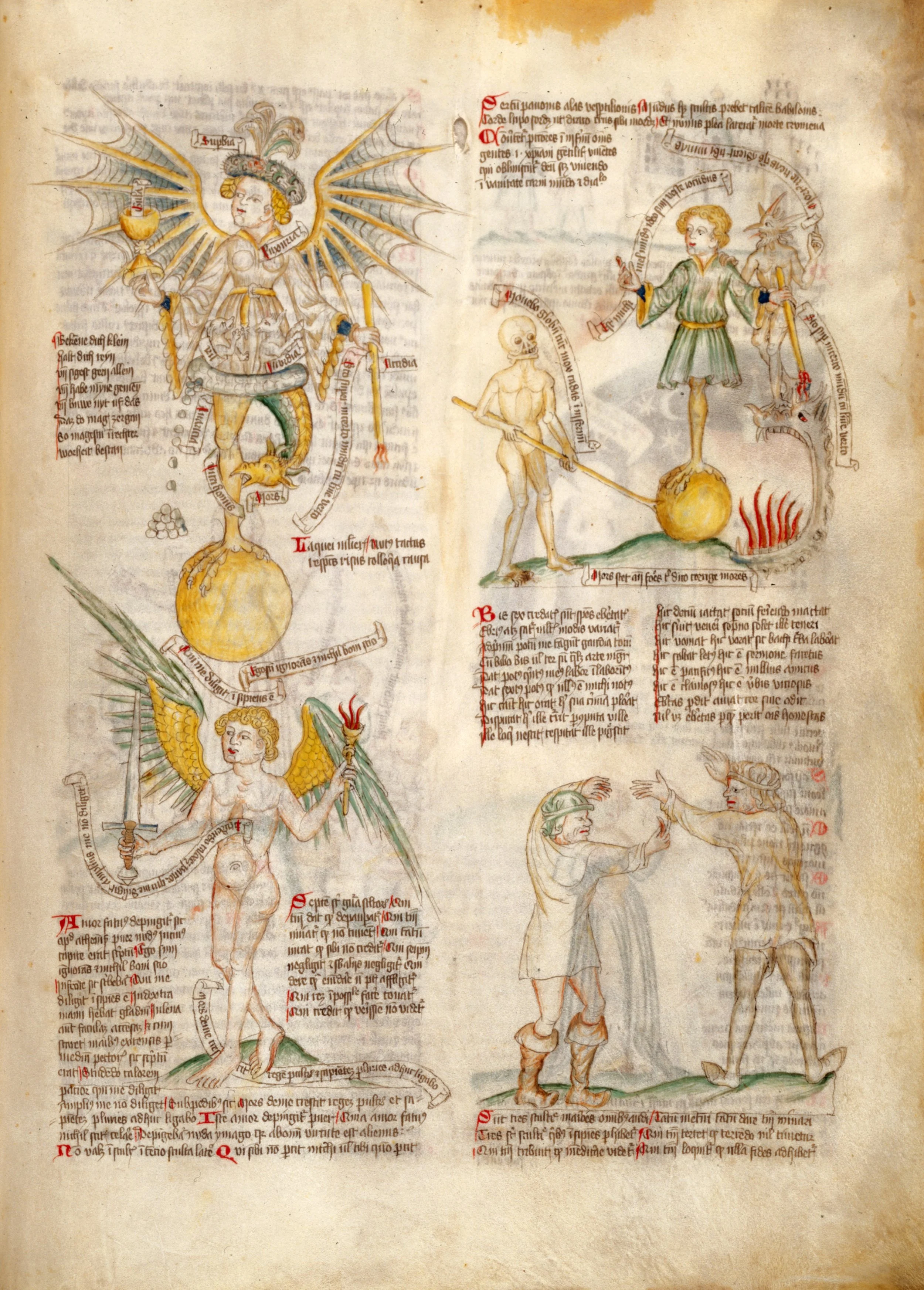

The Unseelie Court is home to the more malevolent fairy folk.

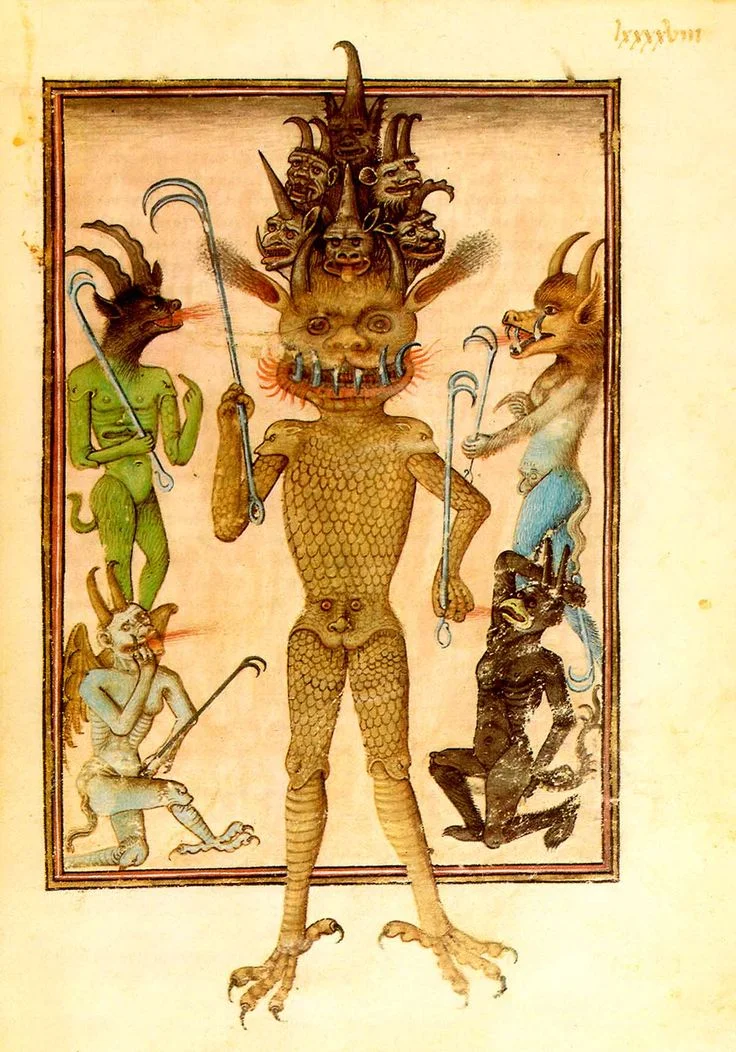

Scottish Fairy Lore and the Seelie and Unseelie Courts

In Scotland, the fairy realm is split into two factions: the Seelie Court, filled with fairies who are mischievous but not entirely malevolent, and the Unseelie Court, where malevolence runs rampant.

Seelie fairies might grant favors to those who respect them, though their “gifts” often have unintended consequences. The Unseelie, however, are another matter entirely. These fairies lurk at crossroads and lonely moors, hunting in packs and carrying off travelers who wander too close to their domain.

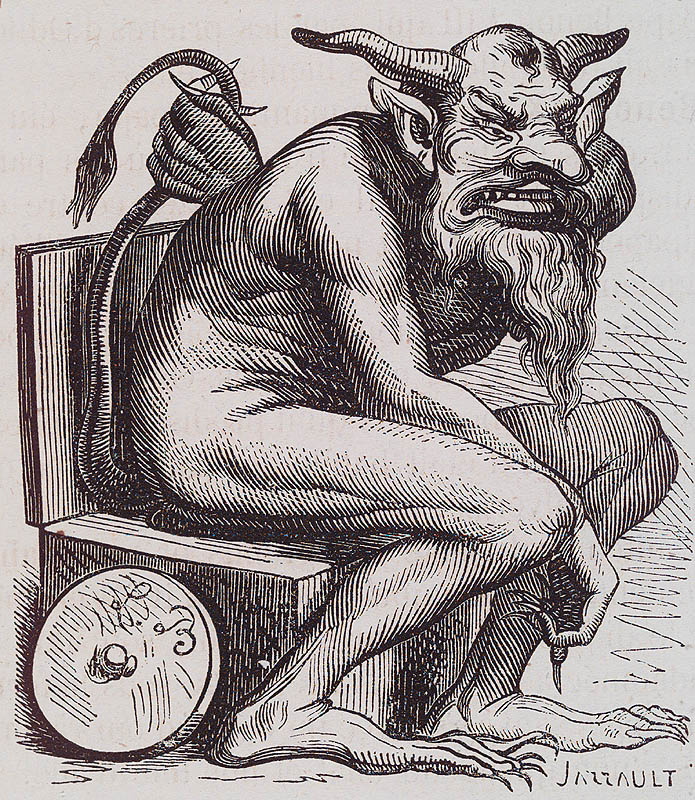

Among them are the redcaps, murderous goblins that dwell in ruined towers, their caps stained with the blood of their victims.

The kelpies, sleek black water-horses, lure riders onto their backs before dragging them into the depths.

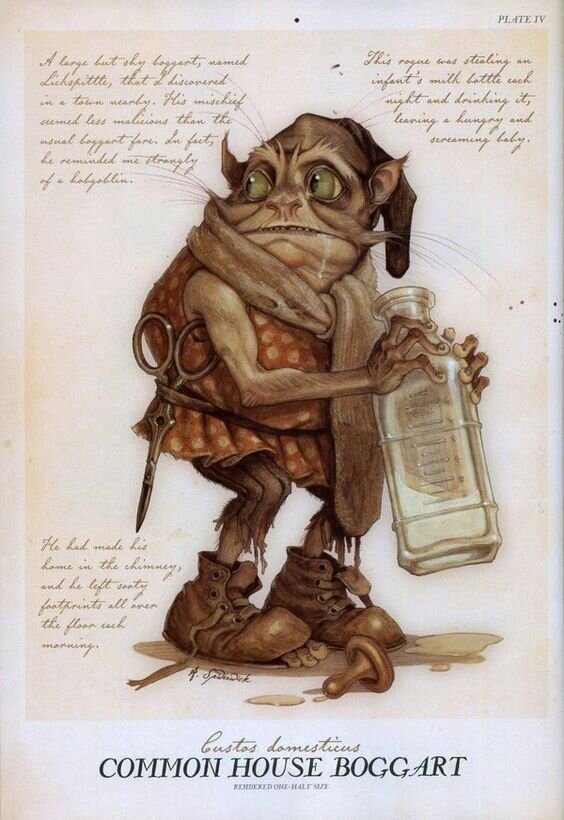

And the brownies, small, shaggy-haired house spirits, help with household chores — so long as they are respected and well fed.

A helpful brownie

Scottish Fae in Popular Tales

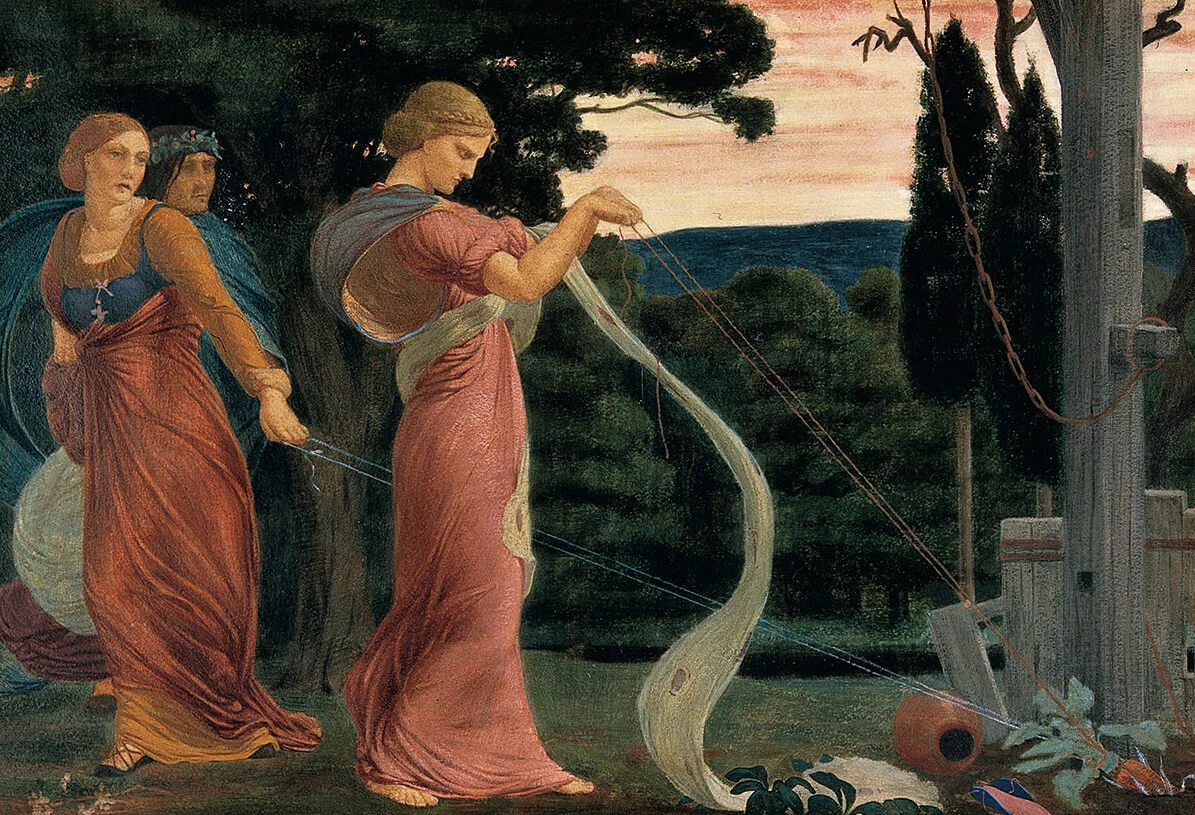

Tam Lin, a classic Scottish ballad, tells of a mortal man, stolen away by the Fairy Queen, who can only be rescued through a terrifying midnight ritual.

In The Falconer by Elizabeth May, Scottish fairies are reimagined as deadly creatures warring against humans.

The Unseelie Court’s dangerous and dark magic is woven into Holly Black’s The Cruel Prince series, where the Fae are as beautiful as they are treacherous.

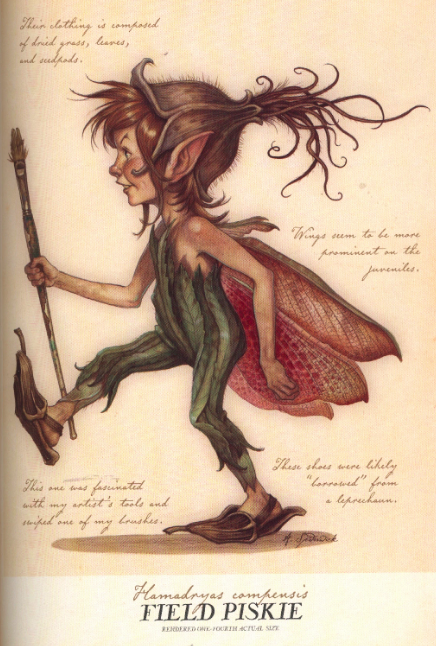

A plague of pesky pixies

English and Welsh Fairies: Tricksters, Ghosts and the Wild Hunt

In the misty forests and moors of England and Wales, the fairy folk take on many forms — some charming, some terrifying, all deeply tied to the land.

The pixies of Devon and Cornwall are small, impish creatures with pointed ears and mischievous grins, known for leading travelers astray with will-o’-the-wisps or tangling horses’ manes into fairy knots. Unlike their Irish or Scottish counterparts, they’re more playful than malicious, though they can still cause trouble if insulted.

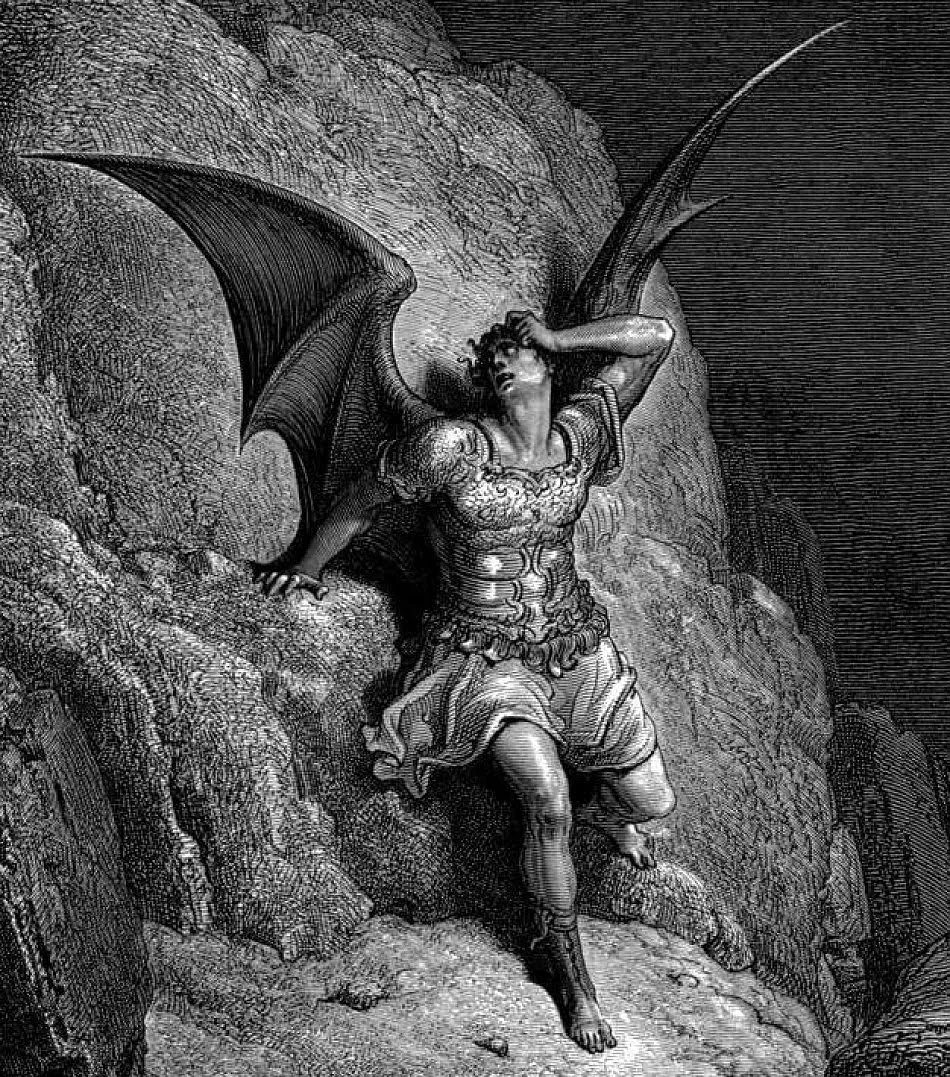

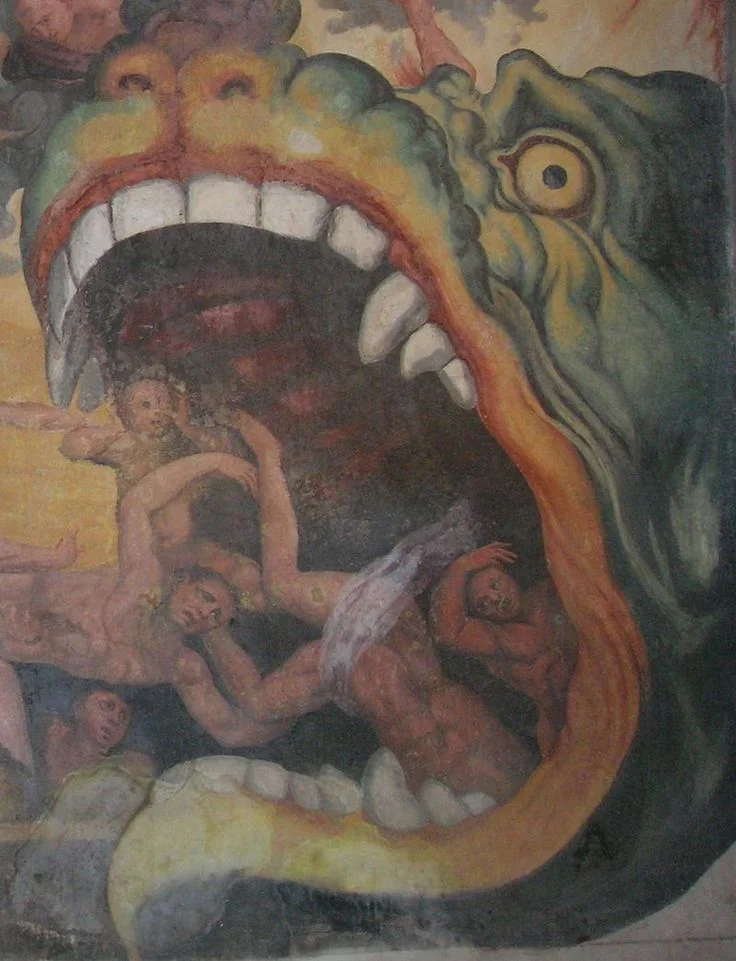

But the Fae of England aren’t all harmless. The Wild Hunt, a spectral procession of ghostly riders led by a dark figure — sometimes the Devil himself, sometimes the mythic Herne the Hunter — thunders across the sky, sweeping up any mortal unlucky enough to cross its path.

Meanwhile, the Green Children of Woolpit, a medieval legend, tell of two strange, green-skinned kids who appeared in a village, speaking an unknown language and claiming to be from an underground world. Were they lost fairies?

Even the land itself is said to be enchanted. The Fairy Paths, invisible roads used by the Fae, must never be obstructed by buildings, or bad luck will follow.

The Fairy Godmothers of later fairy tales may have originated from old beliefs in household fairies, protective spirits who could bestow gifts or curses on infants.

British Fae in Popular Tales

Susanna Clarke’s The Ladies of Grace Adieu reimagines English fairy lore with eerie and elegant storytelling.

Terry Pratchett’s Lords and Ladies features fairies that are predatory and cruel, a nod to their older, darker origins.

The legend of the Wild Hunt plays a major role in Katherine Arden’s The Winter of the Witch and Hellboy comics.

Pixies show up in the Harry Potter series and the game Harry Potter: Wizards Unite.

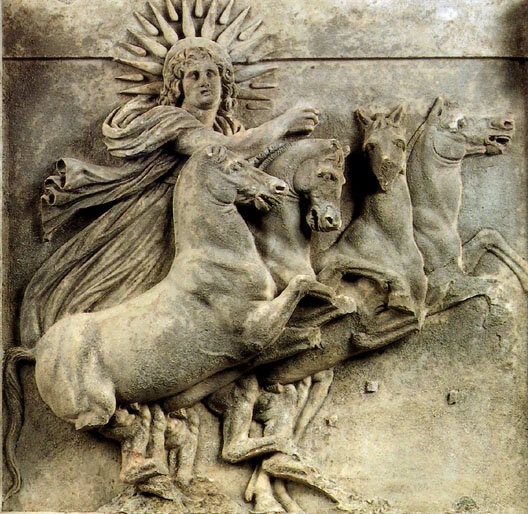

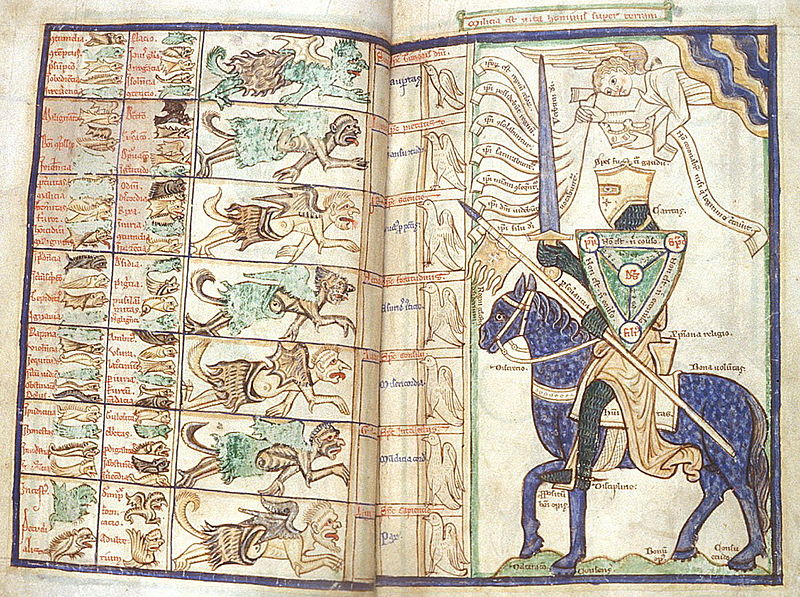

The Álfar, tall, luminous, godlike entities, influenced the elves of Tolkien and D&D.

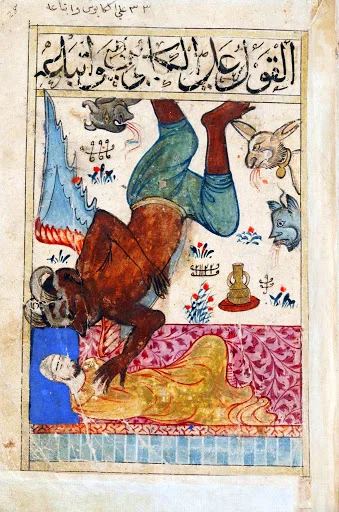

Norse and Germanic Fairies: Elves, Forest Spirits and the Nachtmahr

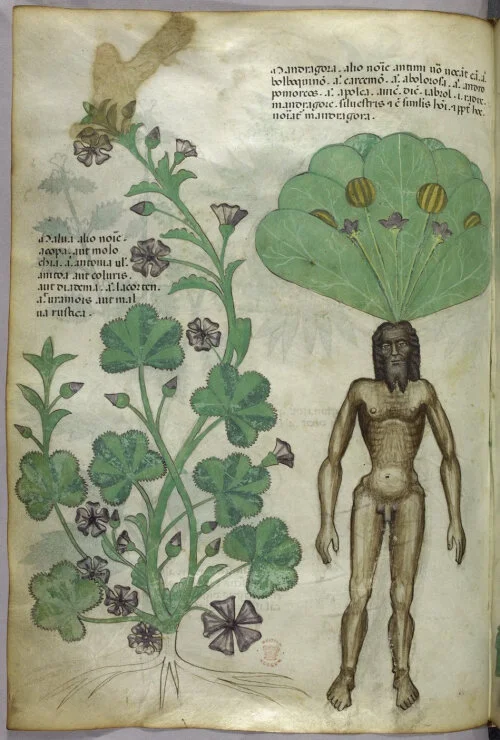

Long before fairies flitted through English gardens, the Norse and Germanic peoples told of the Álfar, or elves: tall, eerily beautiful beings who lived in hidden places and wielded great magic. Unlike later fairies, these elves were closer to minor gods, capable of both great kindness and great wrath. In some sagas, they were luminous, golden-haired beings; in others, they were pale and unsettling, dwelling in mist-shrouded groves and demanding offerings.

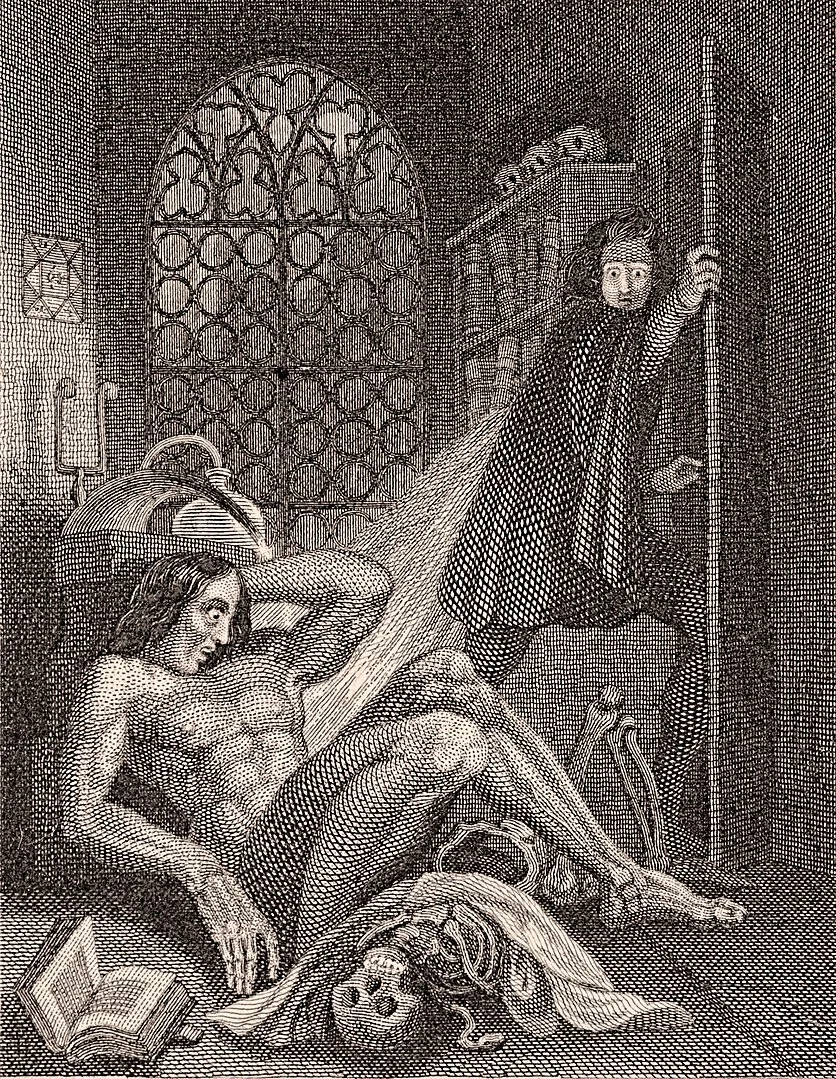

But not all the hidden folk were so noble. The nachtmahr, a twisted shadow spirit, crept into homes at night, sitting on the chests of sleepers and filling their dreams with terror; our word nightmare comes from this legend.

The erlking, a malevolent woodland fairy, lured children to their doom with whispered promises, immortalized in Goethe’s haunting poem.

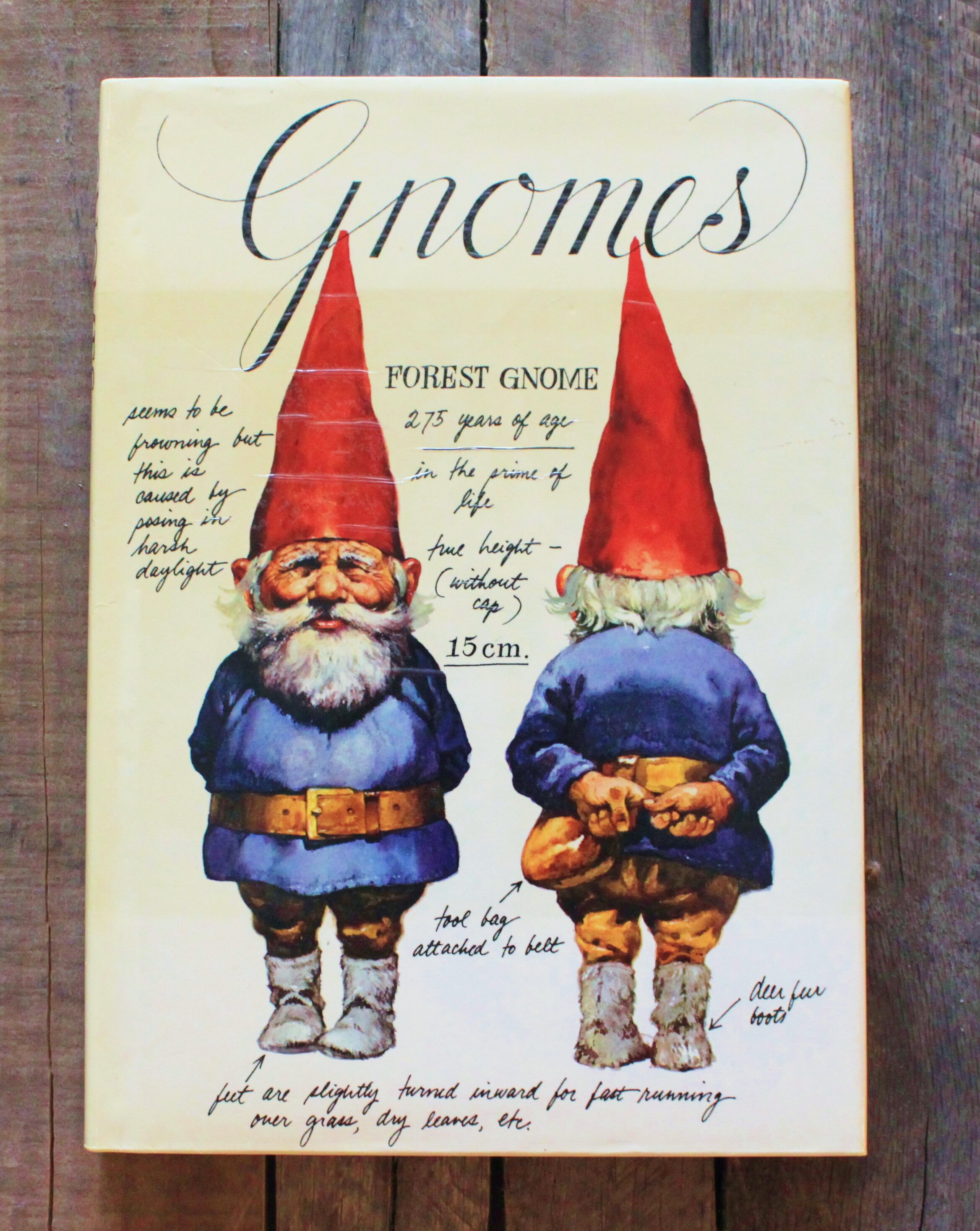

Then there were the kobolds, household spirits that could be either helpful or destructive. Resembling small, gnome-like figures, they lived in homes and ships, protecting the inhabitants if treated well, but turning mischievous or even vengeful if neglected. Some German miners believed kobolds lived in the mines, warning workers of cave-ins — or causing them.

The helpful kobolds of folklore and much different from the lizard-like monsters from D&D.

Norse and German Fae in Popular Tales

The erlking appears in literature from Goethe’s poetry to Jim Butcher’s Dresden Files, always as a chillingly powerful figure.

Tolkien’s elves, with their captivating beauty and ancient wisdom, owe much to Norse and Germanic fairy lore.

Neil Gaiman’s Norse Mythology explores the strange, otherworldly side of the Álfar. (Learn more about the Norse gods.)

A rusalka, the spirit of a drowned young woman, wants men to share her fate.

Slavic Fairies and the Rusalka: Spirits of Water and Wood

Slavic folklore is thick with spirits, many of whom blur the line between fairy, ghost and demon. The rusalka is one of the most haunting: a drowned maiden with pale, luminous skin and long, green-tinted hair, she lingers near lakes and rivers, singing to lure men into the depths. Some legends say she’s vengeful, dragging victims under; others say she’s simply lonely, forever searching for a lost love.

Then there are the domovoi, small, hairy house spirits with glowing eyes. Unlike the trickster fairies of the British Isles, a domovoi was a family guardian, keeping the household safe — so long as it was honored with milk, bread and respect. A neglected domovoi could become vengeful, making life miserable for the home’s inhabitants.

In the dark forests, the leshy reigns: a towering, moss-covered figure with bark for skin and eyes like glowing embers. He’s the master of the woods, able to shift size at will. Travelers who fail to pay their respects may find themselves lost for days, their paths twisting back on themselves under the leshy’s watchful gaze.

The leshy, shapeshifting master of the woods

Slavic Fae in Popular Tales

The Bear and the Nightingale by Katherine Arden weaves Slavic fairy spirits like the domovoi and rusalka into a lush historical fantasy.

The leshy appears in numerous Russian fairy tales and in modern fantasy, including The Witcher series.

The eerie, dreamlike world of the rusalka is captured in Alexander Pushkin’s poetry and Dvořák’s opera.

The diwata and engkantos of the Philippines can be kind or cruel, depending on how you treat them.

The Fairies of Other Cultures

Fairy-like beings exist worldwide, often blending nature spirits, ancestral ghosts and mischievous tricksters.

Tengu love to mess with overly proud samurai — creating illusions, stealing weapons or dragging them into duels they can’t win. I

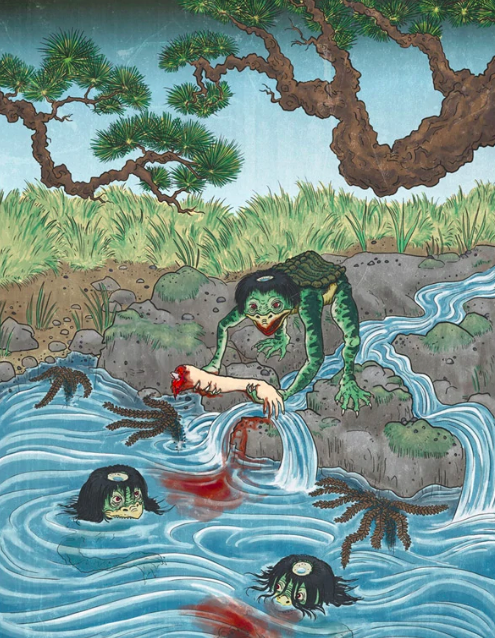

Japanese Yōkai: Creatures like kodama, tree spirits that live in ancient forests, or tengu, bird-like beings who trick travelers and test warriors, share many fairy-like qualities.

Filipino Diwata and Engkantos: Often compared to elves, these spirits of the forests and mountains can be either generous or cruel, depending on how they’re treated.

African and Caribbean Spirits: Figures like the tokoloshe in South Africa — a small, goblin-like trickster — bear similarities to European goblins and sprites.

The trickster tokoloshe from South Africa

Fae From Around the World in Popular Tales

Spirited Away, the Studio Ghibli film, is a masterful portrayal of Japanese fairies and spirits.

The Girl From the Well by Rin Chupeco draws on Japanese and Filipino ghost fairy traditions.

Nalo Hopkinson’s Brown Girl in the Ring weaves Caribbean folklore into a dystopian fairy tale.

Fairy Rings, Time Distortion and Other Fae-Related Mysteries

Step carefully, traveler. A ring of mushrooms in the forest, a strange circle of scorched grass on the moors, an ancient oak with a hollow just large enough for a child to crawl through — these are signs that the Fae have been here. And if you cross into their domain, you may never leave the same.

The Danger of Fairy Rings

Fairy rings are among the most famous — and most feared — phenomena in fairy lore. These naturally occurring circles of mushrooms or oddly vibrant grass are said to be the sites of fairy gatherings. Some legends claim that at night, the Fae emerge from their hidden realm to dance under the moonlight, weaving enchantments into the earth.

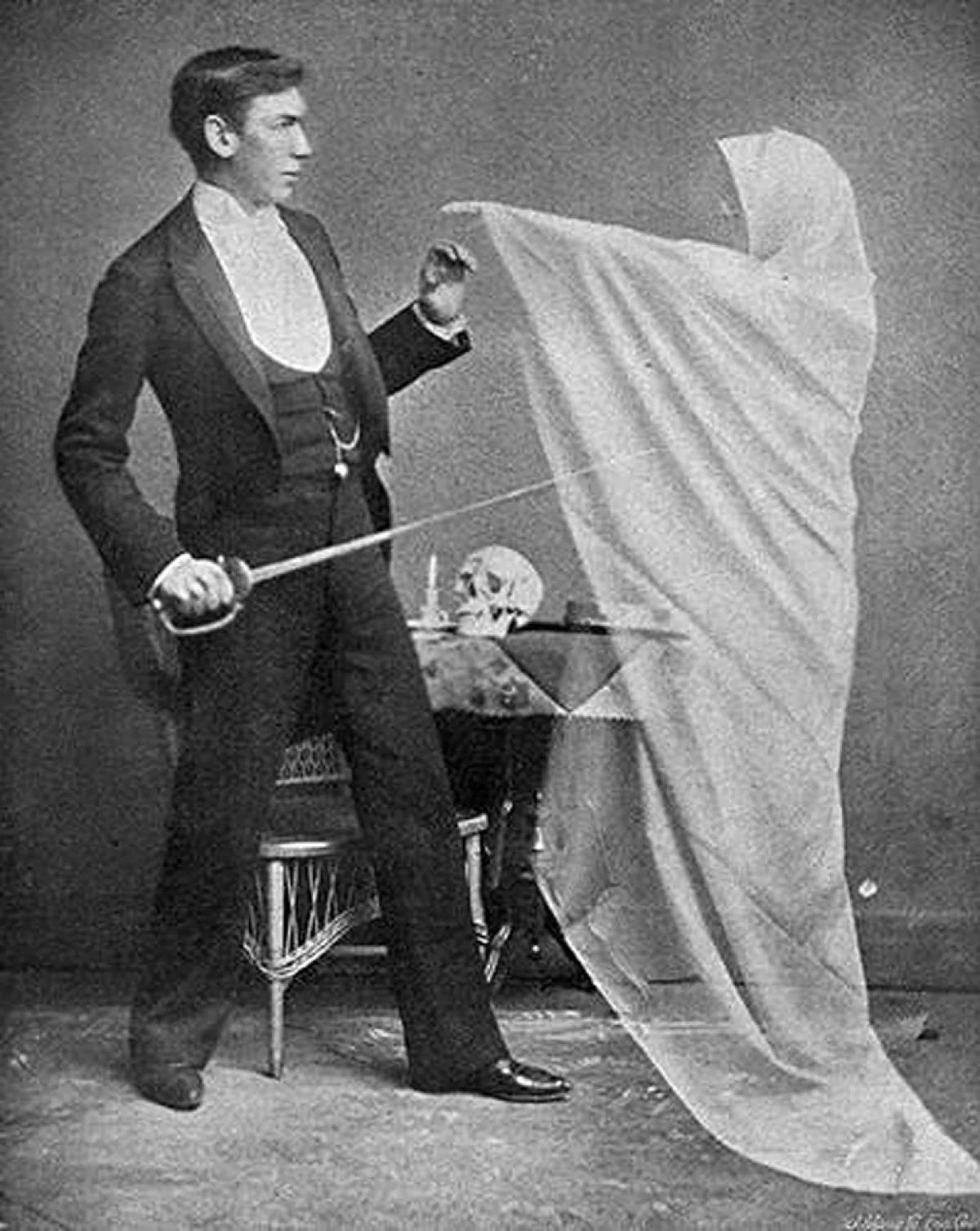

Stepping into a fairy ring, however, is a terrible mistake. Some say you’ll be forced to dance until you collapse from exhaustion, your mind lost in a delirium of music and light. Others warn that time within the ring doesn’t match the world outside. What feels like minutes to you might be years, decades, even centuries beyond the circle’s edge. Many a mortal has stepped inside, only to return as a withered husk or crumble into dust as soon as they leave.

Even outside of fairy rings, the Fae’s ability to warp time is well known. Travelers who accept a fairy’s hospitality — feasting in their halls, drinking their wine — often find that what seemed like a single evening was, in truth, a hundred years. The legend of Oisín, the Irish warrior who rode away with a fairy queen and returned to find his homeland changed beyond recognition, is one of the most haunting examples.

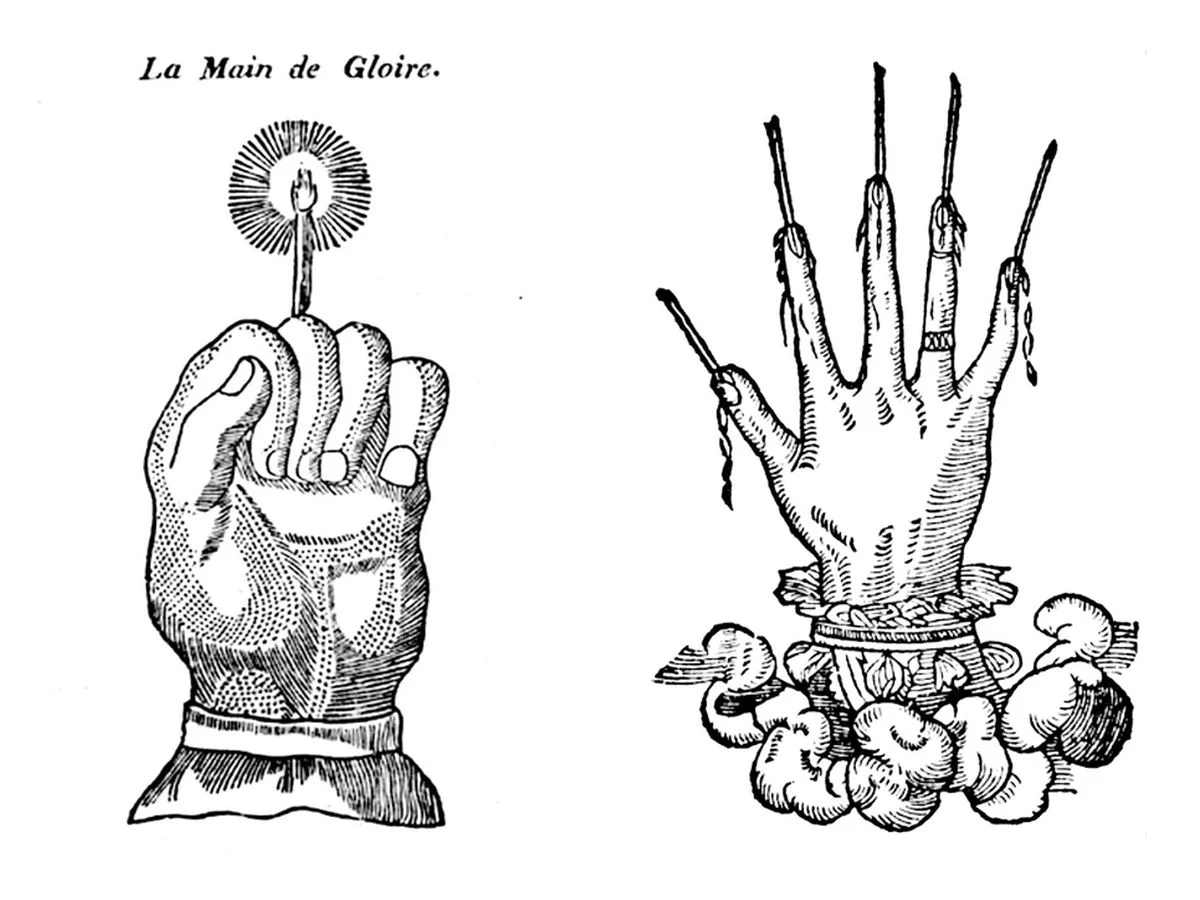

Never Accept a Fairy’s Gift

The Fae are infamous for their tricks, and one of their cruelest is the giving of gifts. A fairy’s boon may seem like a blessing — a pouch of gold coins, an enchanted flute, a charm of protection — but such gifts always come with a price. Some mortals find their gold turns to dead leaves as soon as they step out of the fairy realm. Others find themselves bound by invisible contracts, compelled to serve the Fae for eternity.

I don’t care how hungry you are — never eat anything in fairlyland.

Then there’s the matter of fairy food. It’s a well-known rule that no mortal must ever eat in the land of the Fae. To do so is to bind yourself irrevocably to their realm. Countless legends tell of mortals who took a single bite of fairy bread, only to find themselves unable to leave, their very souls woven into the fabric of that otherworldly place.

The Power of Fairy Music

Fairy music is unlike anything mortal ears have ever heard. It’s haunting, beautiful, impossible to resist. It can put a man into a trance, make a woman dance nonstop until dawn, or lull an entire village into a deep, dreamless sleep. Fiddlers and harpists in Celtic legend often claimed to have learned their skill from the Fae. But such a gift always came with a cost — many returned changed, unable to hear ordinary music without longing for the songs of the otherworld.

One of the most famous tales of fairy music is that of the Pied Piper of Hamelin, who lured away the town’s children with a tune so enchanting the kids followed him into the hills, never to be seen again. Was he simply a vengeful man — or something far older, a fairy trickster leading the children to another world?

How to Protect Yourself From the Fae

The Fae aren’t easily thwarted, but old wisdom offers a few tried-and-true defenses.

1. Iron is your best friend.

Iron is anathema to fairies, burning them like fire. A horseshoe over the door, iron nails driven into the threshold of a home, or even a simple iron key in your pocket can keep them at bay. Many believe that the industrial age — full of iron railways and steel buildings — was what finally drove the fairies into hiding.

2. Keep salt, rowan and red thread handy.

A circle of salt around your home is said to keep fairies from crossing the boundary. Rowan wood, especially in the form of a staff or cross, is a sacred protector against fairy mischief. And red thread tied around your wrist or doorknob prevents enchantments and bewitchment.

3. Never give your name.

Names have power. If a fairy learns your true name, they can control you, call you to their realm at will, or steal your identity altogether. If you must interact with the Fae, use a false name, a nickname, or no name at all.

4. Watch what you say.

Forget those good manners instilled in you as a kid. Thanking a fairy is dangerous — it implies that a debt has been repaid, and fairies despise that. If a fairy grants you a favor, say, “This is well done” or “You have my respect,” but never, ever say “thank you.”

5. Avoid liminal spaces.

Fairies are strongest at twilight, dawn, and during the turning of the seasons (Beltane, Samhain, Midsummer). Crossroads, hollow hills and standing stones are all places where the veil is thin. Step too close, and you may step into their world without even realizing it.

How to Attract Fairies

Not all fairies are malevolent. Some are simply mischievous, while others may be persuaded to lend a little magic to those who honor them properly.

1. Leave offerings.

Fairies appreciate small gifts: bowls of milk, honey, fresh-baked bread or mead. Leave these in a quiet outdoor space, particularly near a fairy ring, a tree hollow or a stream. But never check to see if they’ve been taken; that breaks the spell.

2. Keep a wild garden.

The Fae love untamed beauty. Gardens filled with wildflowers, overgrown ivy and hidden nooks are far more likely to attract them than neat, orderly beds. Plants like foxglove, lavender and thyme are said to be especially beloved by fairies.

3. Speak in riddles and poetry.

The Fae enjoy cleverness. Those who speak in riddles, offer playful banter or recite poetry may find themselves in their favor. Beware, though: If a fairy challenges you to a game of wits and you lose, the consequences will be strange, and sudden — and never fair.

4. Wear silver or bells.

Silver is associated with moonlight and magic, and fairies are drawn to it. Small bells, often worn on clothing, were once thought to please the Fae (though some say they keep trickster spirits away).

5. Celebrate Beltane and Samhain.

These two festivals are when the Fae are closest to the mortal world. Dancing, feasting and lighting candles in their honor may win their favor. Just be careful not to invite the wrong kind.

A Spell to Connect With the Fae

If you wish to invite the presence of the Fae — gently, respectfully and understanding the risks involved — this simple spell will help you call upon their magic.

You’ll need:

A small bowl of milk and honey (a traditional fairy offering)

Fresh wildflowers (such as daisies, foxglove or lavender)

A silver coin

A candle (preferably green or white)

A quiet place in nature, preferably near a tree, stream or fairy ring

The Ritual

As twilight falls, take your offerings to a secluded, peaceful spot where you feel a connection to nature.

Arrange the wildflowers in a small circle and place the bowl of milk and honey in the center.

Set the silver coin beside the bowl as a token of respect.

Light the candle and focus your intent on reaching out to the Fae — not to command, but to invite.

Recite the following incantation:

O spirits fair, of earth and sky,

By moon’s soft glow and stars on high,

With gift of sweet and silver bright,

I call thee forth this sacred night.If friend ye be, then come in grace,

With laughter light and wisdom’s trace.

No harm, no trick, no ill intent,

But blessings true and magic sent.

Let the candle burn for a few moments while you listen to the sounds of the evening. If the wind stirs, if a sudden hush falls, or if you feel a shift in the air — know that the Fae may be near.

Thank them silently, then leave the offerings behind as you depart. Never look back.

A final caution: The Fae don’t grant favors lightly, nor do they take kindly to broken promises. If you feel their presence, treat them with respect. If you receive a sign — a feather, a leaf falling on you, a strange dream — consider it a gift, not a debt to be repaid.

Tread Carefully in the Land of the Fae

The Fae are as fickle as the wind, as ancient as the stones, and as unpredictable as the tide. They’re neither wholly good nor wholly evil, existing in a realm beyond human morality. They can bring fortune or misfortune with a careless flick of a hand, charm you with laughter, or steal you away in a dance that never ends.

Yet still, we seek them. We whisper our wishes into the night, leave offerings on our windowsills, and tell their stories in hushed voices. Perhaps it’s because we, too, long for the hidden places, for the unseen world just beyond our reach.

But if you hear laughter from the trees when no one’s near, or see a flicker of light dancing in the mist, remember: Step lightly, choose your words carefully, and never, ever eat the food. –Wally