Bettelheim’s Freudian analysis of “Cinderella,” “Little Red Riding Hood,” “Hansel and Gretel” and “The Three Little Pigs” helps understand the monster of Supernatural, Season 3, Episode 5.

A little girl’s spirit makes fairy tales come true in this episode of Supernatural — revealing just how violent these stories truly are.

S3E5: “Bedtime Stories”

Monster: Spirit that makes fairy tales come true

Where it’s from: Fairy tales were collected by Charles Perrault in France in 1697, then later in Germany by the Brothers Grimm from 1812-1857.

Description: A cute little girl wearing a white dress that has a red bow with a red ribbon in her hair.

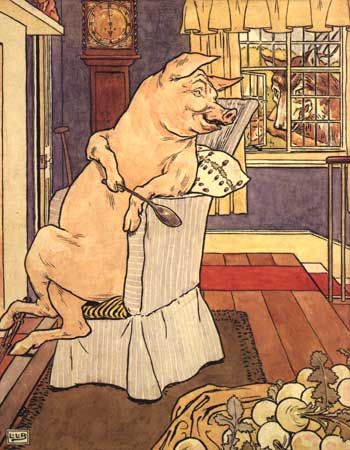

What it does: Something tears apart two brothers, devouring their innards. They were arguing about how to build houses — like the Three Little Pigs. “Actually, those guys were a little chubby,” Dean says with a smirk.

“Many adults today tend to take literally the things said in fairy tales, whereas they should be viewed as symbolic renderings of crucial life experiences.”

Talk of fairy tales always makes me break out Bruno Bettelheim’s seminal work The Uses of Enchantment: The Meaning and Importance of Fairy Tales. And sure, he’s extremely Freudian — his analysis is filled with oral fixations and oedipal complexes — but he helps get at the root of these stories and why they resonate with children on a subconscious level.

“Many adults today tend to take literally the things said in fairy tales, whereas they should be viewed as symbolic renderings of crucial life experiences,” Bettelheim writes.

“The Three Little Pigs” reveals the dangers of following the pleasure principle.

“The Three Little Pigs”

Bettelheim explains how this fairy tale teaches children that they have to tame their id as they move into adulthood:

The littlest pig built his house with the least care out of straw; the second used sticks; both throw their shelters together as quickly and effortlessly as they can, so they can play for the rest of the day. Living in accordance with the pleasure principle, the younger pigs seek immediate gratification, without a thought for the future and the dangers of reality. … Only the third and oldest pig has learned to behave in accordance with the reality principle: He is able to postpone his desire to play, and instead acts in line with his ability to foresee what may happen in the future.

The third Little Pig acted like a sensible adult — and was able to keep the wolf at bay.

Of course, the bad guys are something within us, according to Bettelheim:

The wolf’s badness is something the young child recognizes within himself: his wish to devour, and its consequences — the anxiety about possibly suffering such a fate himself. So the wolf is an externalization, a projection of the child’s badness — and the story tells how this can be dealt with constructively.

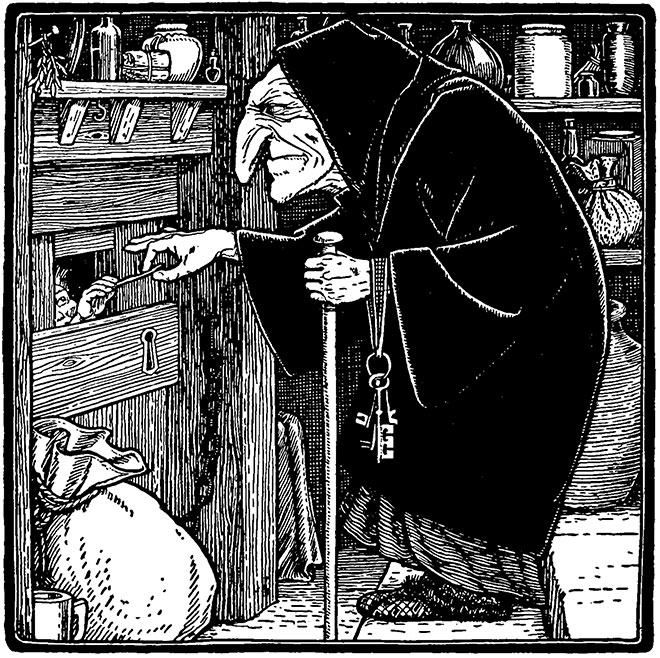

“Hansel and Gretel” plays upon kids’ dominant fear, according to Bettelheim: being deserted by their parents.

“Hansel and Gretel”

A little old lady invites in two lost hikers — they’re “deep in the woods,” just like Hansel and Gretel — and drugs their cherry pie. Then she grabs a knife, slits the man’s throat and stabs him repeatedly, smiling all the while like a sweet grandma.

Outside the window, the little girl watches, pleased.

“The fairy tale expresses in words and actions the things which go on in children’s minds,” Bettelheim explains.

In terms of the child’s dominant anxiety, Hansel and Gretel believe that their parents are talking about a plot to desert them. A small child, awakening hungry in the darkness of the night, feels threatened by complete rejection and desertion, which he experiences in the form of fear of starvation.

The parents in “Hansel and Gretel” attempt to abandon their children. It’s hard not to imagine Bettelheim is referring to breastfeeding here:

It is the child’s anxiety and deep disappointment when Mother is no longer willing to meet all his oral demands which leads him to believe that suddenly Mother has become unloving, selfish, rejecting. Since the children know they need their parents desperately, they attempt to return home after being deserted.

The gingerbread house, as seen in this old advertisement, is actually a symbol of…a good mother, who offers up her breast for nourishment?!

There’s a lot of symbolism packed into that gingerbread house, according to Bettelheim:

Carried away by their uncontrolled craving, the children think nothing of destroying what should give shelter and safety. …

The child recognizes that, like Hansel and Gretel, he would wish to eat up the gingerbread house, no matter what the dangers. …

A gingerbread house, which one can “eat up,” is a symbol of the mother, who in fact nurses the infant from her body. Thus, the house at which Hansel and Gretel are eating away blissfully and without a care stands in the unconscious for the good mother, who offers her body as a source of nourishment.

While the fairy tale is scary, children appreciate the fact that Hansel and Gretel ultimately trick and kill the witch.

And then there’s that cannablistic witch:

The witch, who is a personification of the destructive aspects of orality, is as bent on eating up the children as they are on demolishing her gingerbread house. …

A witch as created by the child’s anxious fantasies will haunt him; but a witch he can push into her own oven and burn to death is a witch the child can believe himself rid of. As long as children continue to believe in witches — they always have and always will, up to the age when they no longer are compelled to give their formless apprehensions humanlike appearance — they need to be told stories in which children, by being ingenious, rid themselves of these persecuting figures of their imagination.

The murders on Supernatural are obviously connected to these fairy tales. And in the originals, there weren’t happily-ever-afters; the Grimm tales are gruesome. Originally they had sex, violence and cannibalism. “It got sanitized over the years,” Sam says, “turned into Disney flicks and bedtime stories.”

There’s a frog on the path in front of them. Dean’s finally convinced, though he adds, “I’ll tell you one thing: There’s no way I’m kissing a damn frog.”

When Sam sees a pumpkin and a mouse, he thinks of Cinderella’s carriage. “Dude, could you be more gay?” Dean says. I hope he has to make out with the frog for that comment.

A young woman is handcuffed in the kitchen. Her stepmother went crazy and abused her. Sound familiar?

Children relate to Cinderella, whose place is in the ashes of the hearth, because they, too, like to get dirty — and they feel guilty about their oedipal desires.

“Cinderella”

“Cinderella” has its origins in China even before the 9th century, when it was first written down. Bettelheim points out that that particular Asian country has had a controversial past involving foot fetishism and abuse of women:

The modern hearer does not connect sexual attractiveness and beauty in general with extreme smallness of the foot, as the ancient Chinese did, in accordance with their practice of binding women’s feet.

The conflict in “Cinderella” involves her nasty stepsisters, which Bettelheim justifiably ties to sibling rivalry.

Despite the name “sibling rivalry,” this miserable passion has only incidentally to do with a child’s actual brothers and sisters. The real source of it is the child’s feelings about his parents. …

Fearing that in comparison to [a child’s sisters or brothers] he cannot win his parents’ love and esteem is what inflames sibling rivalry. This is indicated in stories by the fact that it matters little whether the siblings actually possess greater competence.

Cinderella acquires her name by hanging out in the cinders of the hearth. Bettelheim posits that children connect with this uncleanliness:

Some of the child’s pervasive feelings of worthlessness have their origin in his experiences during and around toilet training and all other aspects of his education to become clean, neat and orderly. … As clean as a child may learn to be, he knows that he would much prefer to give free rein to his tendency to be messy, disorderly and dirty.

At the end of the oedipal period, guilt about desires to be dirty and disorderly becomes compounded by oedipal guilt, because of the child’s desire to replace the parent of the same sex in the love of the other parent.

It makes every child identify with Cinderella, who is relegated to sit among the cinders. Since the child has such “dirty” wishes, that is where he also belongs. … This is why every child needs to believe that even if he were thus degraded, eventually he would be rescued from such degradation and experience the most wonderful exaltation — as Cinderella does.

Then again, there might be something actually noble and desirable about Cinderella’s station by the fire:

We are so accustomed to thinking of living as a lowly servant among the ashes of the hearth as an extremely degraded situation that we have lost any recognition that, in a different view, it may be experienced as a very desirable, even exalted position. In ancient times, to be the guardian of the hearth — the duty of the Vestal Virgins — was one of the most prestigious ranks, if not the most exalted, available to a female.

Bettelheim adds that “in many societies ashes were used for ablutions as a means of cleansing oneself.”

The Fairy Godmother gives Cinderella the means to attend the ball in style — but she has to leave early to keep her virginity intact.

And it wouldn’t be a Freudian reading of “Cinderella” if there wasn’t a stand-in for the vagina, right?

A tiny receptacle into which some part of the body can slip and fit tightly can be seen as a symbol of the vagina. Something that is brittle and must not be stretched because it would break reminds us of the hymen; and something that is easily lost at the end of a ball when one’s lover tries to keep his hold on his beloved seems an appropriate image for virginity. … Cinderella’s running away from this situation could be seen as her effort to protect her virginity.

The godmother’s order that Cinderella must be home by a certain hour or things will go very wrong … is similar to the parent’s request that his daughter must not stay out too late at night because of his fear of what may happen if she does.

Then again, maybe the shoe means a marriage commitment:

[I]n many stories it is the prince who slips the shoe on. This might be likened to the groom’s putting the ring on the finger of the bride as an important part of the marriage ceremony, a symbol of their being tied together henceforth.

Bettelheim saw the glass slipper as symbolic of a vagina — more specifically, a hymen.

And there’s a creepy ending to “Cinderella” that Disney decided to leave out:

For the last time the stepsisters, with the active help of the stepmother, try to cheat Cinderella out of what rightly belongs to her. Trying to fit their feet into the shoe, the stepsisters mutilate them. …

They engaged in symbolic self-castration to prove their femininity; bleeding from the place on the body where this self-castration occurred may be another demonstration of their femininity, as it may stand for menstruation.

Back on Supernatural, the creepy little girl is there, but flickers and disappears, leaving a shiny red apple where she was standing. That’s symbolic of Snow White’s long sleep — sort of like the coma the doctor’s daughter is in.

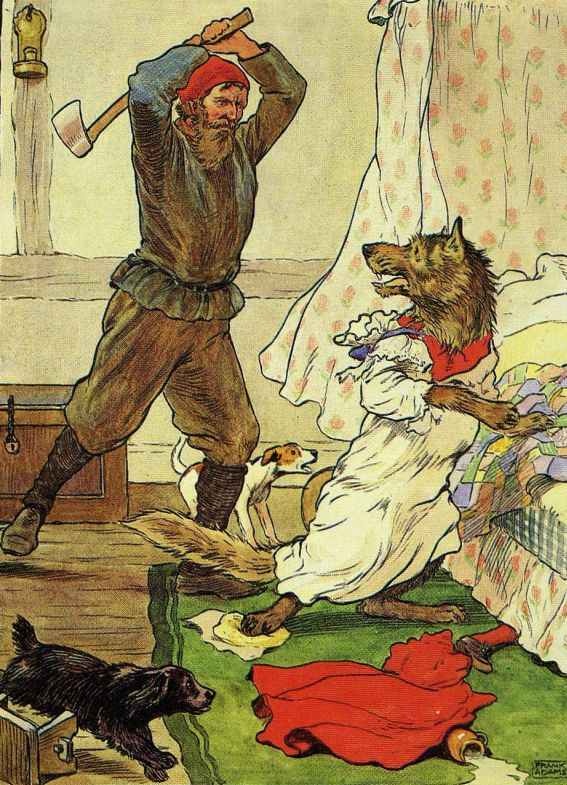

Turns out he’s reading her Brothers Grimm fairy tales. Why aren’t we surprised? When he reads “Little Red Riding Hood,” the Big Bad Wolf (well, the dude with the Wile E. Coyote tattoo, that is) attacks a grandmother and kidnaps her granddaughter, who happens to be wearing a red hoodie.

Little Red Riding Hood is given a red cloak, which shows she’s been sexualized at too young an age — leaving her prey to the Big Bad Wolf, a stand-in for lustful men.

“Little Red Riding Hood,” or “Little Red Cap”

In the famous tale, Little Red Riding Hood wanders off the path, is tricked by the Big Bad Wolf and gets swallowed whole. Bettelheim sees this as a coming of age story, rife with sexual metaphors:

Little Red Cap tries to understand, when she asks Grandmother about her big ears, observes the big eyes, wonders about the large hands, the horrible mouth. Here is an enumeration of the four senses: hearing, seeing, touching, and tasting; the pubertal child uses them all to comprehend the world.

“Little Red Cap” in symbolic form projects the girl into the dangers of her oedipal conflicts during puberty, and then saves her from them, so that she will be able to mature conflict-free.

It’s ultimately a story about young women coming to terms with men, who are

split into two opposite forms: the dangerous seducer who, if given in to, turns into the destroyer of the good grandmother and the girl; and the hunter, the responsible, strong, and rescuing father figure.

It is as if Little Red Cap is trying to understand the contradictory nature of the male by experiencing all aspects of his personality: the selfish, asocial, violent, potentially destructive tendencies of the id (the wolf); the unselfish, social, thoughtful and protective propensities of the ego (the hunter).

Little Red Cap is universally loved because, although she is virtuous, she is tempted; and because her fate tells us that trusting everybody’s good intentions, which seems so nice, is really leaving oneself open to pitfalls.

It’s no coincidence that our heroine is wearing red:

All through “Little Red Cap,” in the title as in the girl’s name, the emphasis is on the color red, which she openly wears. Red is the color symbolizing violent emotions, very much including sexual ones. The red velvet cap given by Grandmother to Little Red Cap thus can be viewed as a symbol of a premature transfer of sexual attractiveness. …

Little Red Cap’s danger is her budding sexuality, for which she is not yet emotionally mature enough.

Bettelheim, channeling Freud, gets creepy when he starts talking about how Red, standing in for all little girls, really wants to be seduced by her father:

The story on this level deals with the daughter’s unconscious wish to be seduced by her father (the wolf). …

It is this “deathly” fascination with sex — which is experienced as simultaneously the greatest excitement and the greatest anxiety that is bound up with the little girl’s oedipal longings for her father, and with the reactivation of these same feelings in different form during puberty. …

“Little Red Cap” externalizes the inner processes of the pubertal child: The wolf is the externalization of the badness the child feels when he goes contrary to the admonitions of his parents and permits himself to tempt, or to be tempted, sexually. When he strays from the path the parent has outlined for him, he encounters “badness,” and he fears that it will swallow up him and the parent whose confidence he betrayed. But there can be resurrection from “badness,” as the story proceeds to tell.

When Little Red Riding Hood is cut out of the wolf’s belly, it’s a metaphor for her being reborn as a young woman.

I suppose it makes sense that kids would see a pregnant woman (such as Mommy) and think that the baby has to be cut out of her:

Little Red Cap has to be cut out of the wolf’s stomach as if through a Caesarean operation; thus the idea of pregnancy and birth is intimated. With it, associations of a sexual relation are evoked in the child’s unconscious.

By the end of the fairy tale, Red has undergone the sort of hero’s journey Joseph Campbell wrote of:

Little Red Riding Hood’s childish innocence dies as the wolf reveals itself as such and swallows her. When she is cut out of the wolf’s belly, she is reborn on a higher plane of existence; relating positively to both her parents, no longer a child, she returns to life a young maiden.

How to defeat it: Listen to the spirit. Once the message is received, the killings will stop.

Bet you’ll never read (or watch) a fairy tale the same way you did before, will you? –Wally