Mesomaerican legends, including Mayahuel and Ehécatl’s doomed love, drunk Tlacuache the possum and 400 rabbits suckled on pulque.

Mesoamerican myths are pretty crazy. Take the fertility goddess Mayahuel, who lactated pulque, which intoxicated the 400 rabbits she gave birth to.

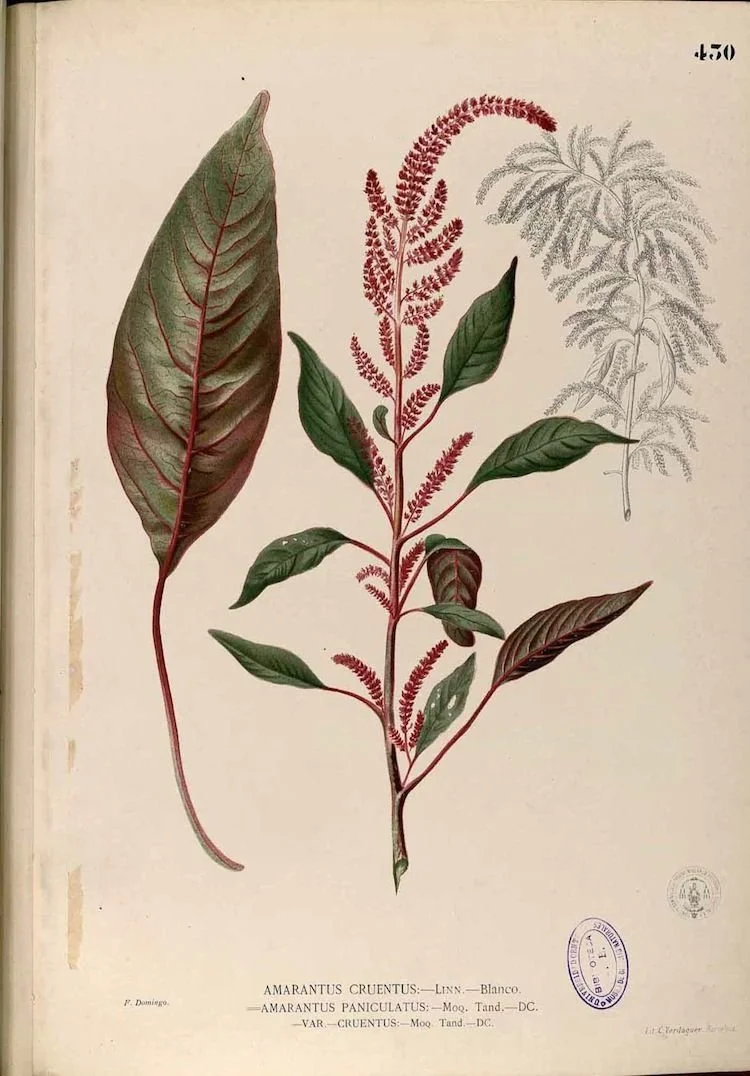

Aside from being a source of sustenance, the agave, or maguey as it’s referred to in Mexico, was revered and respected as a sacred plant by the ancient peoples of Mesoamerica.

The desert succulent is distinguished by a rosette of strong fleshy leaves that radiate from the center of the plant. Fibers from its tough spiny leaves were used to make rope or fabric for clothing, and the barbed tips made excellent sewing needles. Devotees and priests would pierce their earlobes, tongues or genitals with the thorns and collect the blood as an offering to the gods. An antiseptic poultice of maguey sap and salt was used in traditional medicine and applied to wounds. The plant is also the source of pulque, a beverage made from its fermented sap, and many years later, distilled as mezcal and tequila.

Agave being used to treat a head wound

As a final act, the maguey poetically blooms in the final throes of its life cycle. A mutant asparagus-like stalk emerges from the center of the plant, reaching 25 to 40 feet high before it flowers and dies.

Drink of the Gods

In Aztec times, the milky and sour mildly alcoholic beverage was highly prized and strictly limited to consumption by a select few, including priests, pregnant women, the elderly and tributes offered up for ritual sacrifice. The priests believed that the resulting intoxication put them in an altered state and allowed them to communicate directly with the gods. The consequences of illegally imbibing outside of this group were so serious that the convicted faced death by strangulation.

So what are the myths and folklore stories about agave and pulque? As with myths around the world, there are multiple variations, and while researching stories about agave I found myself falling down a rabbit hole. I couldn’t quite decide what the definitive versions were, so here are my interpretations.

The gorgeous (personally we don’t see it) Mayahuel was rescued from her evil grandmother, then torn apart and fed to demons, before eventually becoming the first agave.

The Legend of Mayahuel, Whose Lovely Bones Became the First Agave

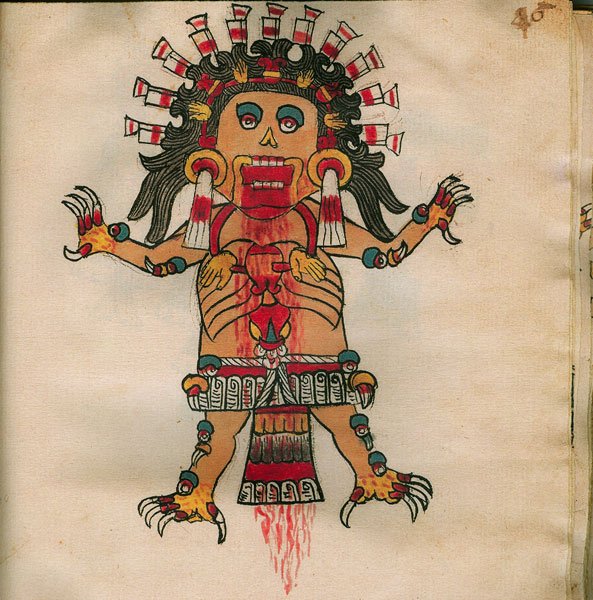

When the universe as we know it was formed, so too was a ferocious and bloodthirsty race of light-devouring demons known as tzitzimime. It was said that life ebbed from their fleshless female forms. They were easily recognizable by their shiny black hair, skeletal limbs ending in clawed hands, and blood red tongues resembling a sacrificial knife wagging from their gaping maws. Their wide-open starry eyes allowed them to see through the darkness.

The tzitzimime were ferocious demons who sucked light and life from this world.

These monstrous beings ruled over the night sky and wore gruesome necklaces loaded with severed human hands and hearts — trophies from the steady diet of human sacrifices required to appease them.

The tzitzimime cloaked the earth in darkness, and in return for ritual bloodshed, permitted the sun to rise and move across the sky. It’s a fair guess to say that a large number of lives were lost, as the Aztecs believed that if darkness won, the sun would be lost forever, the world would end, and the tzitzimime would descend from the skies and gobble up humankind.

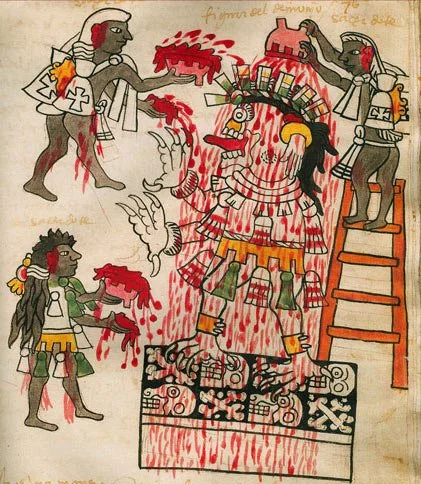

The tzitzimime demons were insatiable for sacrifices of human blood.

Hidden in the sky among the tzitzimime was a beautiful young maiden by the name of Mayahuel. Mayahuel was imprisoned by her grandmother, Tzitzímitl, the oldest and most malevolent demoness of the brood.

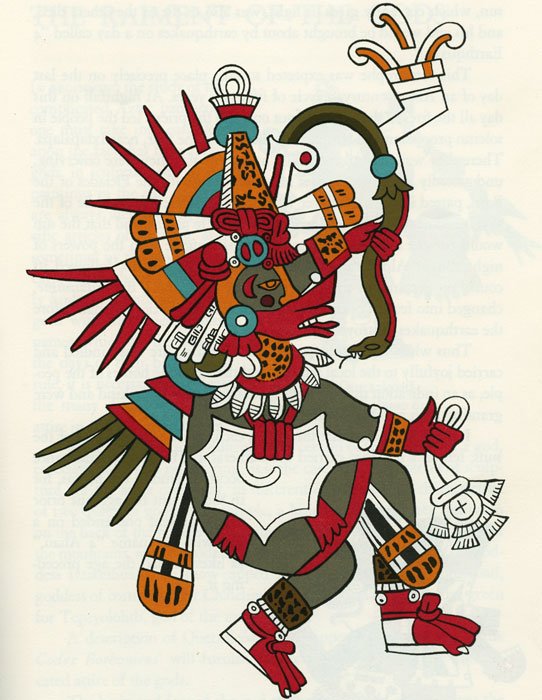

Tzitzímitl’s insatiable desire for human sacrifice angered Ehécatl, the god of wind and rain.

One evening he rose up into the night sky to confront her, but instead discovered Mayahuel. Struck by her beauty, he immediately fell in love and convinced her to descend from the heavens to become his paramour.

Ehécatl, god of wind and rain, tried his best to save poor Mayahuel from Tzitzimitl.

When Tzitzímitl discovered that Mayahuel was missing, she exploded into a violent rage and commanded her demon servants to find her granddaughter. The pair assumed the form of trees and stood side by side so that their leaves would caress one another whenever the wind blew.

Time passed, but their disguise was no match for the furious Tzitzímitl. The sky turned gray with clouds that heralded a major storm, followed by lightning and thunder. When the evil spirit finally found Mayahuel, she tore her from the ground and fed her to her legions of tzitzimime.

The skeletal demoness Tzitzímitl with her necklace of severed human hearts and hands

Ehécatl was unharmed. He avenged Mayahuel’s death by killing Tzitzímitl and returned light to the world. Still overcome with grief, he gathered the bones of his beloved and buried them in a field. As his tears saturated the arid soil, Mayahuel’s remains transformed and emerged from the earth as the first agave. After getting a taste of the elixir that came from the plant, Ehécatl decided to share his creation with humankind.

For some reason, the possum god Tlacuache was responsible for creating the course of rivers. They’re curvy because he got drunk on pulque.

The Tale of Tlacuache: Why a River Runs Its Course

Another Mesoamerican tale connects pulque with the creation of rivers. According to the story, Tlacuache, a possum god, was responsible for assigning the course of rivers. While going about his day foraging for food, he happened upon an agave. Using his human-like hands, he dug into one of its leathery leaves. A sweet honeyed sap oozed from the cuts, and Tlacuache stuck his snout into the maguey and lapped up the liquid with glee.

After having his fill, he returned to his den and dreamt of returning to the plant the next day. Tlacuache had a remarkable talent for finding food and remembering exactly where it was found. What he didn’t know, though, is that the nectar had fermented overnight and now contained alcohol. The marsupial accidentally overindulged and became intoxicated. Finding himself disoriented, he stumbled and wandered this way and that, until he eventually found his way home.

Over time, Tlacuache’s circuitous meandering was reflected in his work. Any river in Mexico that bends or doesn’t follow a straight line was due to Tlacuache drinking pulque and plotting the river’s course while he was tipsy. In fact, some say he was the very first drunk.

Suck on this: The fertility goddess Mayahuel didn’t have milk in her breasts — she had pulque.

Pulque Breast Milk and being drunk as 400 Rabbits

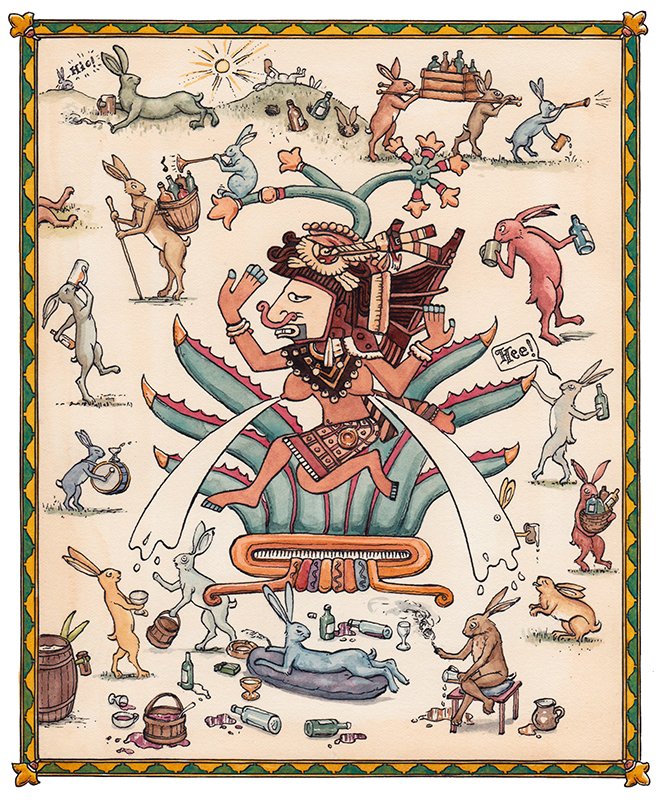

Last but not least is the fantastical story of the mythical 400 drunken rabbits whose behavior even Beatrix Potter would have found excessive.

In Aztec mythology, Patecatl was the Lord of 13 Days and the credited discoverer of the squat psychedelic peyote cactus. One evening, he and Mayahuel, who in this story is a fertility goddess, had a no-strings-attached tryst, resulting in an unusual pregnancy. Months later, the proud mother bore a litter of 400 fluffy little bunnies.

Naturally, being the goddess of the agave, Mayahuel’s multiple breasts lactated pulque, which she used to nourish her children. It’s safe to say that her divine offspring didn’t understand the concept of moderation and were frequently found in various states of inebriation.

Mayahuel had a one-night stand with the Lord of 13 Days — and ended up having a litter of 400 rabbits!

The 400 rabbits each depict a different stage of inebriation.

The siblings were known as the Centzon Totochtin and represented the varying degrees of intoxication one can attain while under the influence of alcohol. One of the children, Ometochtli (Two Rabbit), a god who represented duality, was associated with that initial burst of courage that comes after a couple of drinks. Conversations feel more important, and everyone around you becomes more attractive. His brother Macuiltochtli (Five Rabbit) was one of the gods of excess — the equivalent of having too much of a good thing, and waking up the next day with a pounding headache.

Ometochtli, or Two Rabbit, was the god of the courage you get after a couple of drinks — and the start of beer-goggling.

This fellow is going to regret being like Macuiltochtli, or Five Rabbit, and drinking to excess. He’s gonna be hungover tomorrow.

If you’re drunk as 400 rabbits, you’re beyond wasted.

For the Aztecs, the concept of infinity started at 400. A couple of drinks is OK; consuming your body weight in booze not so much. Moral of the story: If you drink more than you can handle, whether you’re a small animal or otherwise, you’ll be carried away by a colony of 400 rabbits. –Duke

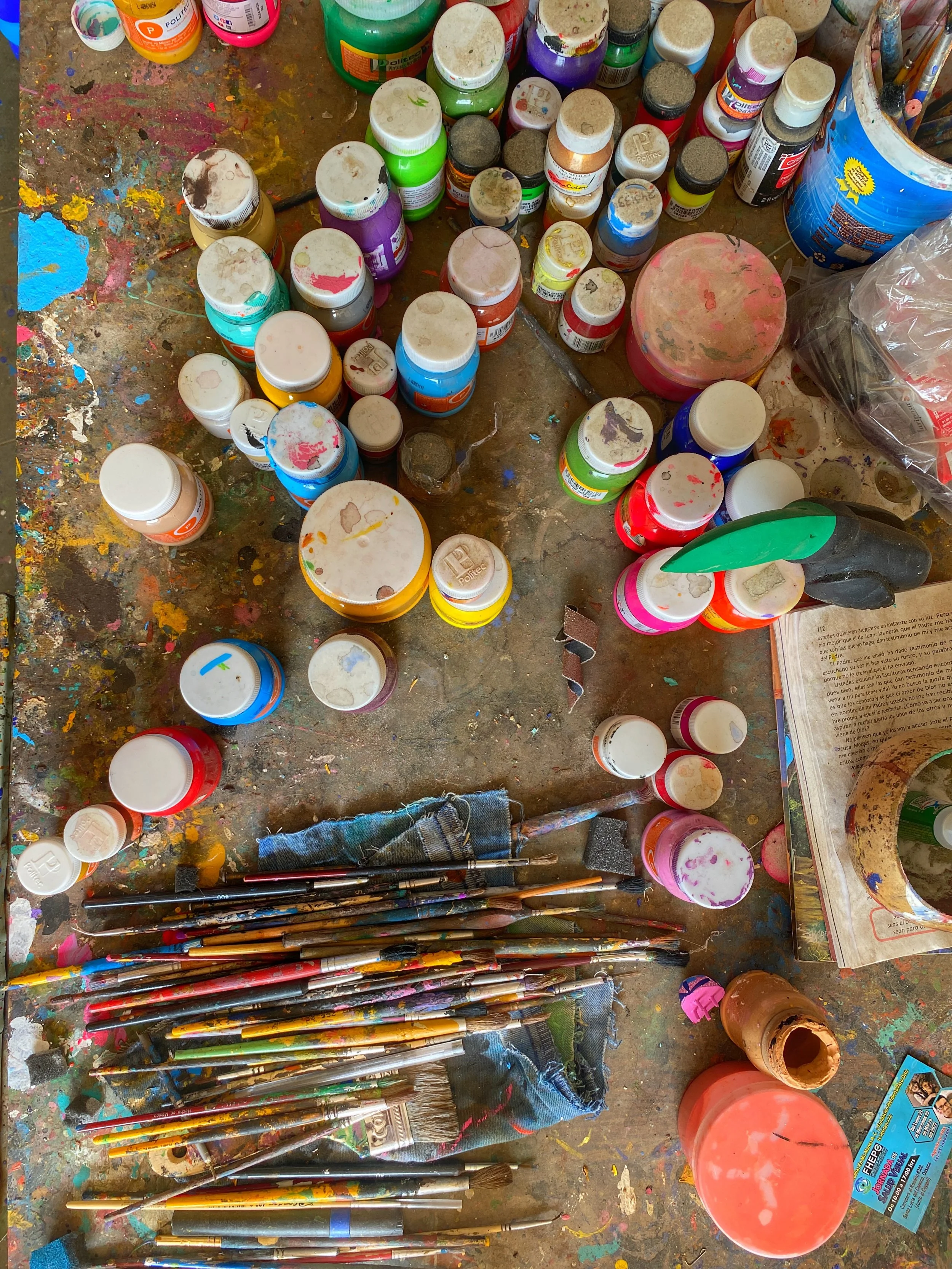

Learn How Mezcal Gets Made

Another drink made from the agave, mezcal is much more artisanal than tequila, with numerous factors influencing the taste of each batch — and that’s what makes it so interesting.