The iconic Monument to the Revolution in CDMX offers an observation deck up top, tombs of famous revolutionaries and a museum below.

The Monument to the Revolution was going to be a much bigger structure but opened in its present incarnation in 1938.

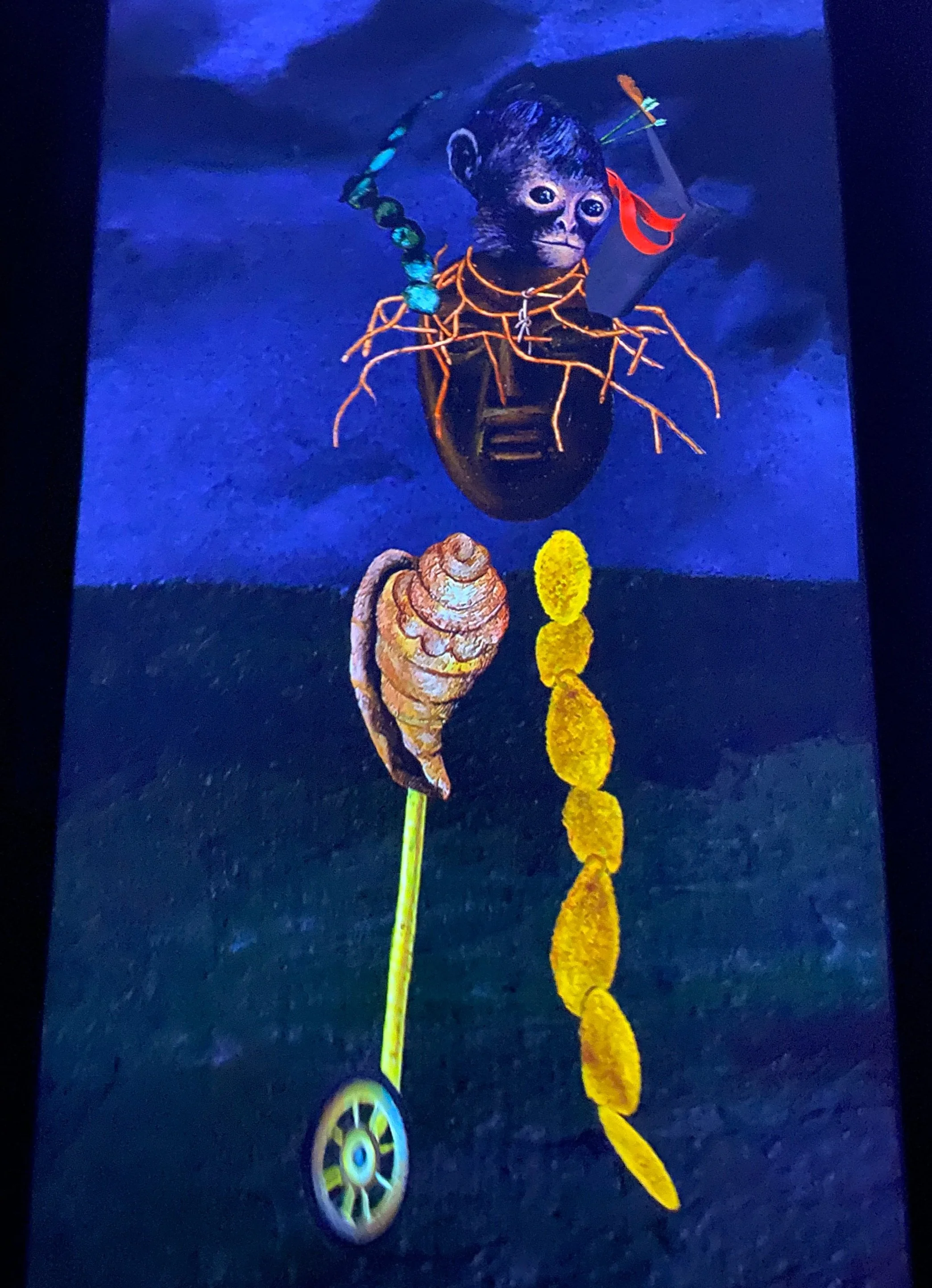

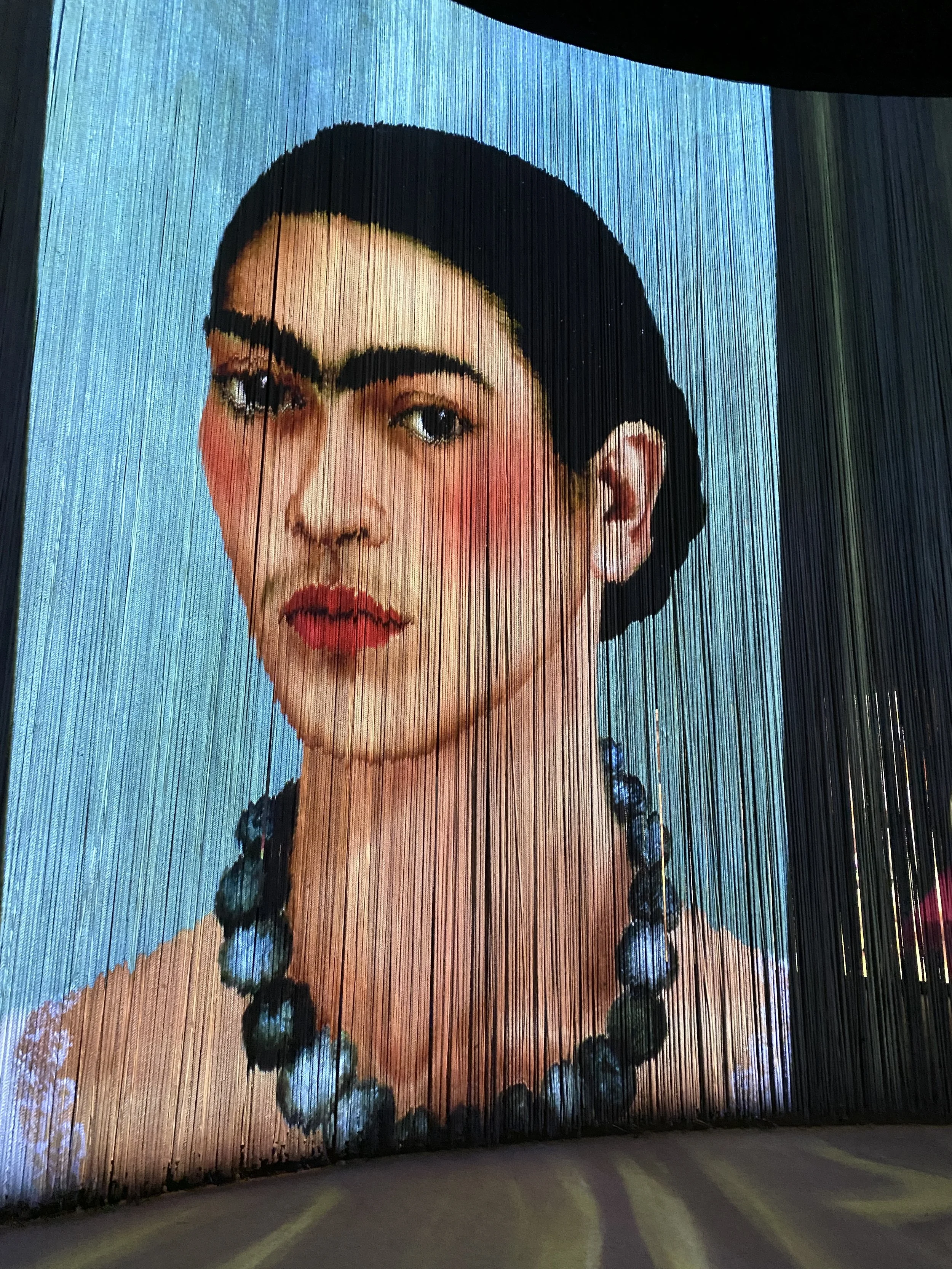

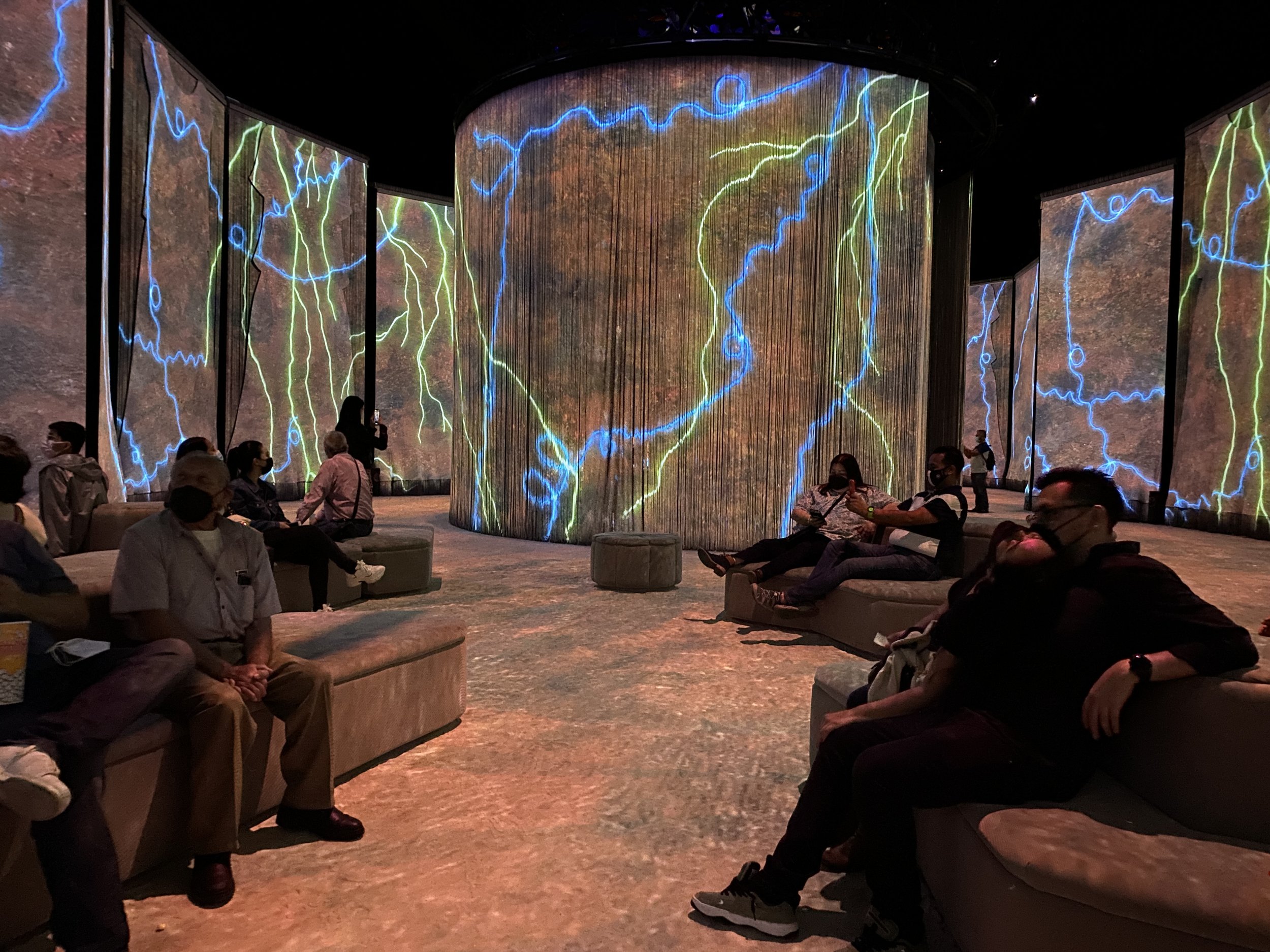

We had a bit of time before seeing the Immersive Frida show at Frontón México across the street. So we wandered through the Plaza de la República, admiring the Monumento a la Revolución (Monument to the Revolution) from all angles. We didn’t end up going inside (either up to the top or down below, which are both options).

At the time, what we knew about this monument barely scratched the surface. It has hidden depths — literally.

Here are seven fun facts about the Monument to the Revolution in Mexico City.

The Monumento a la Revolución is the tallest triumphal arch in the world and has become a CDMX icon.

Fast facts about the Monument to the Revolution

Opened: 1938

Designer: Carlos Obregón Santacilia

Height: 220 feet

Style: Art Deco and Mexican Social Realism

A local market sets up shop in the Plaza de la República in front of the Monumento a la Revolución.

1. It’s the tallest triumphal arch in the world.

Take that, Arc de Triomphe! Paris’ monument might arguably be more famous, but Mexico City’s rises higher than any other, at 220 feet. (The Arc de Triomphe is a paltry 164 feet high.)

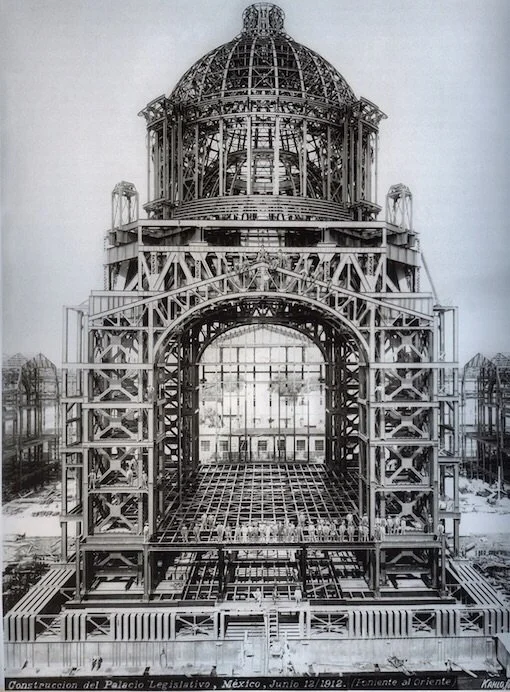

A historic shot of the structure first being built, from 1912. The monument was originally going to be a palatial government building, the Palacio Legislativo Federal.

2. It was originally supposed to be a massive legislative building.

The structure was planned to be the Palacio Legislativo Federal (Federal Legislative Palace). No royalty would have resided in this palace — instead, it was to house legislators and bureaucrats during the corrupt reign of Porfirio Díaz (more on him below). But then the Mexican Revolution ignited and the project was abandoned.

The metal structure that was to serve as the core of the building languished for over 20 years, rusting away. But then Mexican architect Carlos Obregón Santacilia convinced the government to transform the structure into a monument to the heroes of the Mexican Revolution.

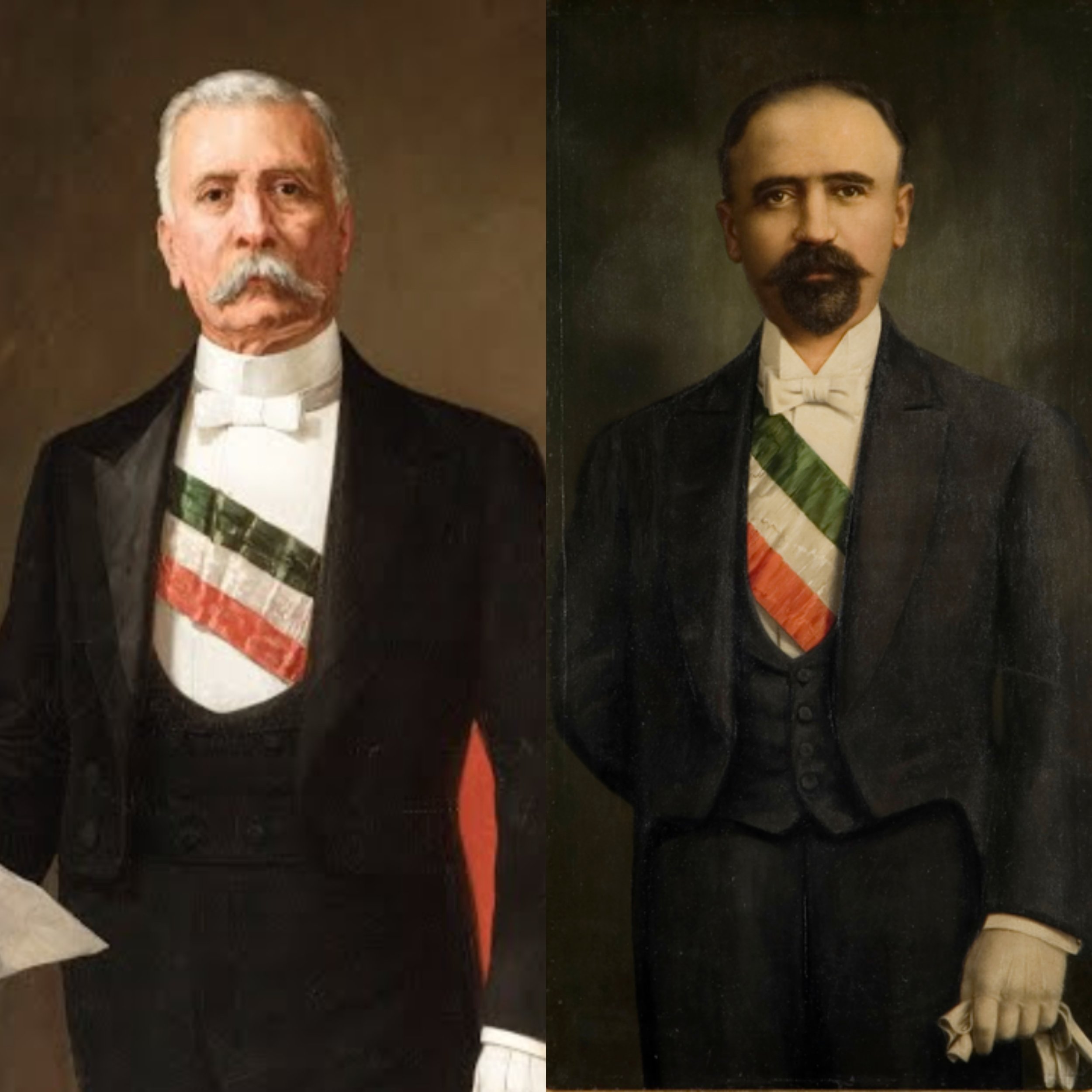

The dictator Porfirio Díaz (left) was ousted during the Mexican Revolution, and Francisco I. Madero (right) was set up as the president of the new democracy.

3. The Mexican Revolution deposed a crooked ruler and instituted democracy for the nation.

A hero of the battle that defeated invading French troops (why Cinco de Mayo is celebrated every year), Díaz ran for president of Mexico. But when he lost, the sore loser launched a coup in 1876 and seized power, ruling nonstop, aside from a four-year break, until 1911. Francisco I. Madero, a presidential contender who was jailed when he threatened to unseat Díaz, became a leader of the pro-democracy movement. He called Mexicans to arms on November 20, 1910 (that date is now Revolution Day). The revolutionaries succeeded, and Díaz’s reign ended when he was forced into exile in France. It’s estimated that 2 million people died during the revolution, or 1 in 8 Mexicans.

The (in)famous bandit Pancho Villa, folk hero of the Mexican Revolution, is interred in a pillar of the Monumento a la Revolución.

4. The monument also serves as a mausoleum for Mexican presidents and rebels.

If I had done a bit of research beforehand, I would definitely have insisted on heading inside the monument. The bases of each of the four main pillars house the tombs of some of the most famous Mexican revolutionaries: Pancho Villa (bandit), Madero (president), Plutarco Elías Calles (general, then president) and Lázaro Cárdenas (another general, another president).

The glass elevator in the middle of the monument takes visitors up to a viewing platform by the cupola.

5. There’s an observation deck at the top of the monument.

The Monument to the Revolution underwent an extensive renovation in 2010, when a new glass elevator was added. You can easily spot it rising right into the center of the structure. It takes visitors up to a viewing platform inside the copper-clad cupola — though I bet the ride up is the best part. Part of the structure has been left exposed to reveal the steel innards that support it. If this interests you, I’ve heard you can book a short tour during your visit.

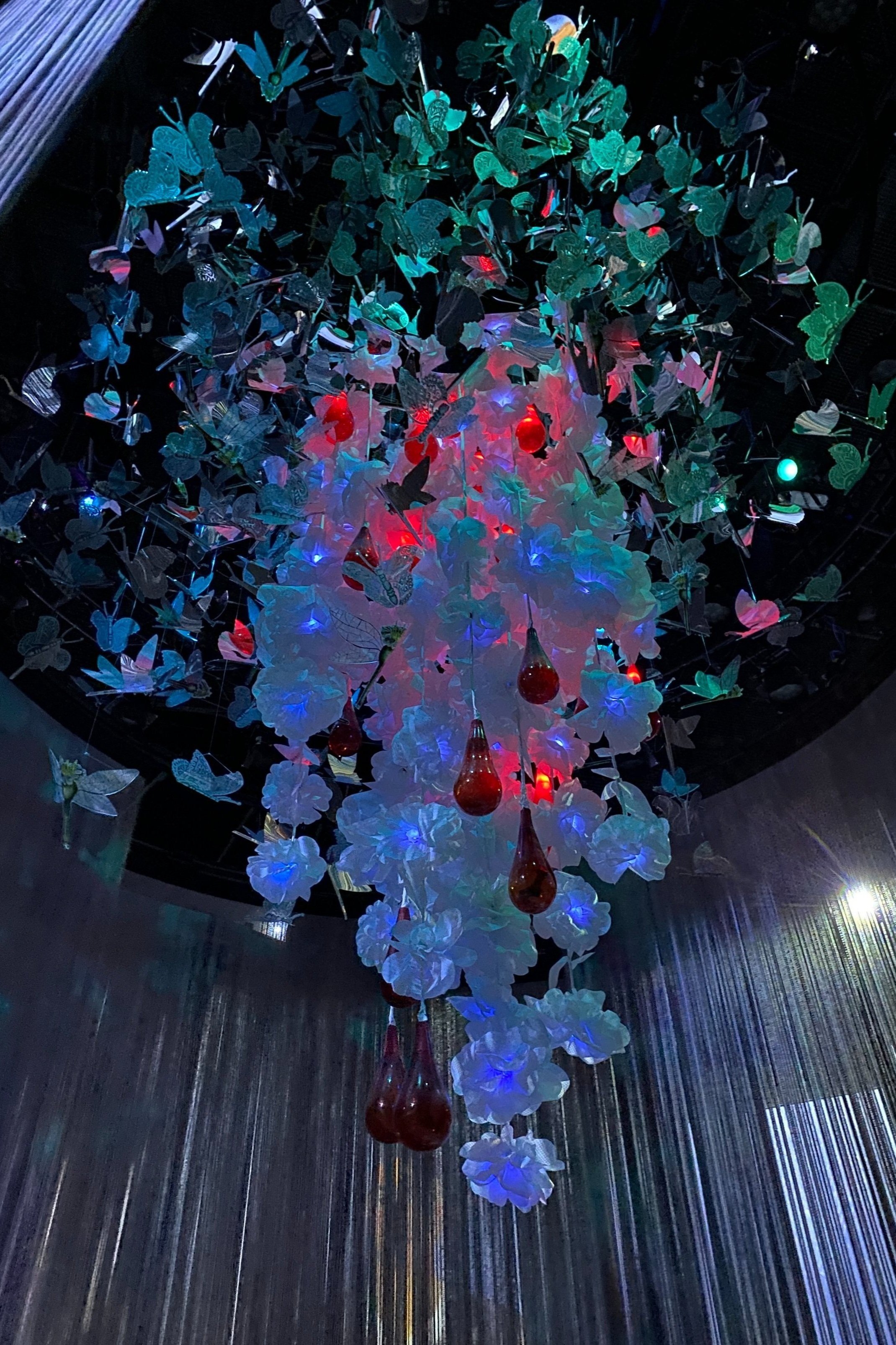

6. And, under all those tons of concrete, there’s a museum and art exhibit space below.

Head down to the basement to find an art gallery as well as the National Museum of the Revolution. The museum (self-described as avant-garde — we’ll have to take their word for it) includes a series of rooms that each deal with a time period of Mexico’s history.

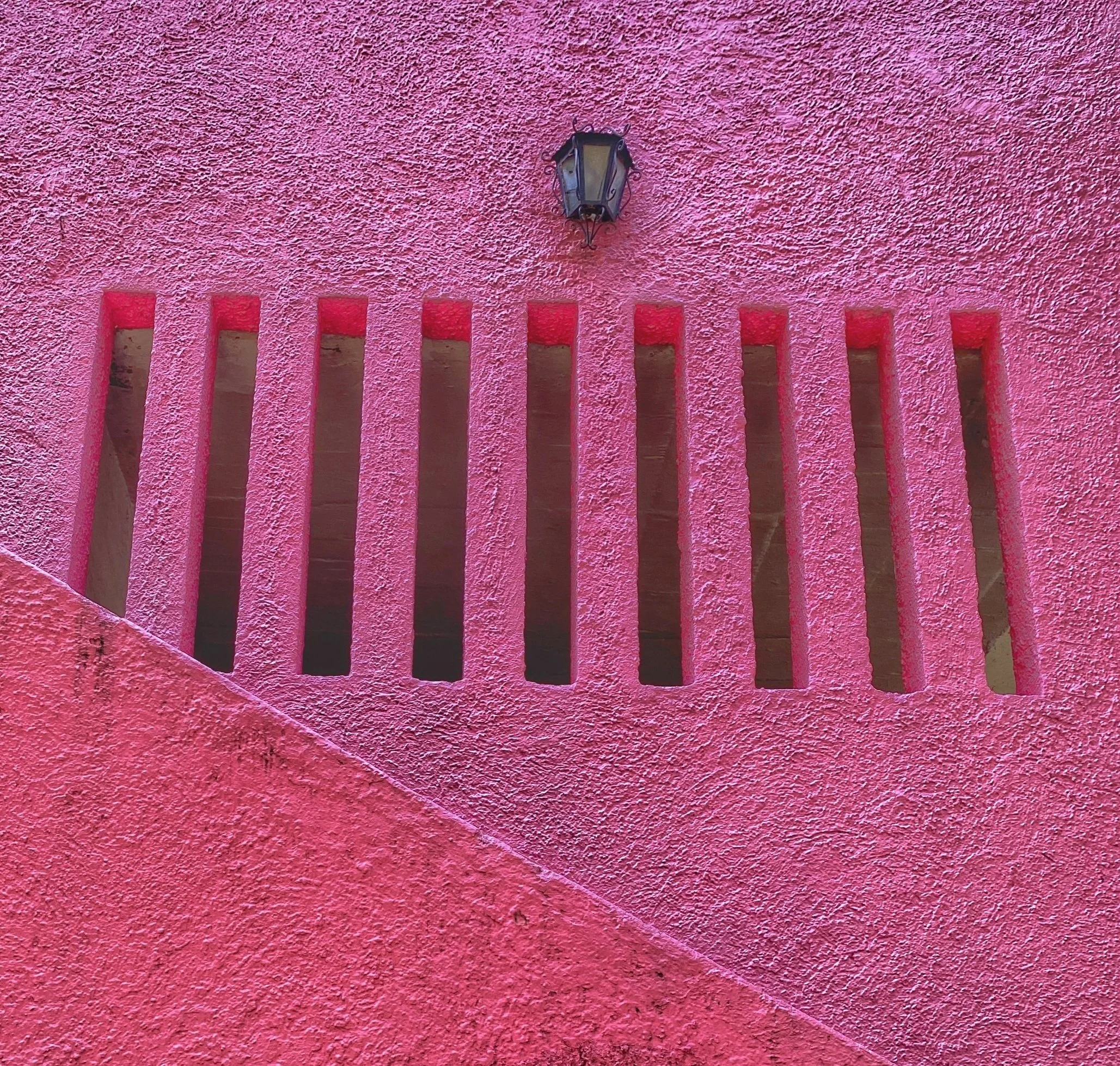

To one side of the monument, there’s a sunken garden that offers an escape from the hustle and bustle of Mexico City.

7. The Plaza de la República has a nice hangout spot.

The day we walked around the plaza, there was a small market by the monument’s main entrance. I do love how vendors can set up shop pretty much anywhere in Mexico City. This market seemed to be more for locals, with stalls selling shirts, hats, purses and the like, with some food stands mixed in.

On the other side of the plaza, there’s a sunken garden. The walls are high enough to block out the busy intersections that surround the square — certainly visually if not aurally. It’s a great place to seek a bit of serenity right in the midst of a commercial district.

So, even though there’s so much going on inside, above and below the Monumento a la Revolución, I never beat myself up for missing something while traveling. I’m always happy to have a reason to go back — especially to as magical a city as CDMX. –Wally

Keeping the Plaza de la República clean

Monumento a la Revolución

Plaza de la República S/N

Tabacalera

Cuauhtémoc

06030 Ciudad de México

México