Hinduism is said to have millions of gods — but in practice, a few dozen take center stage. Here’s your guide to the most significant deities and avatars, including Shiva, Ganesha, Vishnu, Saraswati, Krishna, Hanuman, Lakshmi and Kali.

If you’ve ever heard that Hinduism has “330 million gods,” you might picture an endlessly expanding pantheon with so many characters you could spend a lifetime learning about them all.

The truth is more layered. That astronomical number isn’t a census so much as a poetic way of saying the divine is infinite, manifesting in countless forms and aspects.

In practice, certain deities emerge again and again — in temple carvings, festival processions, devotional songs and stories passed down through generations.

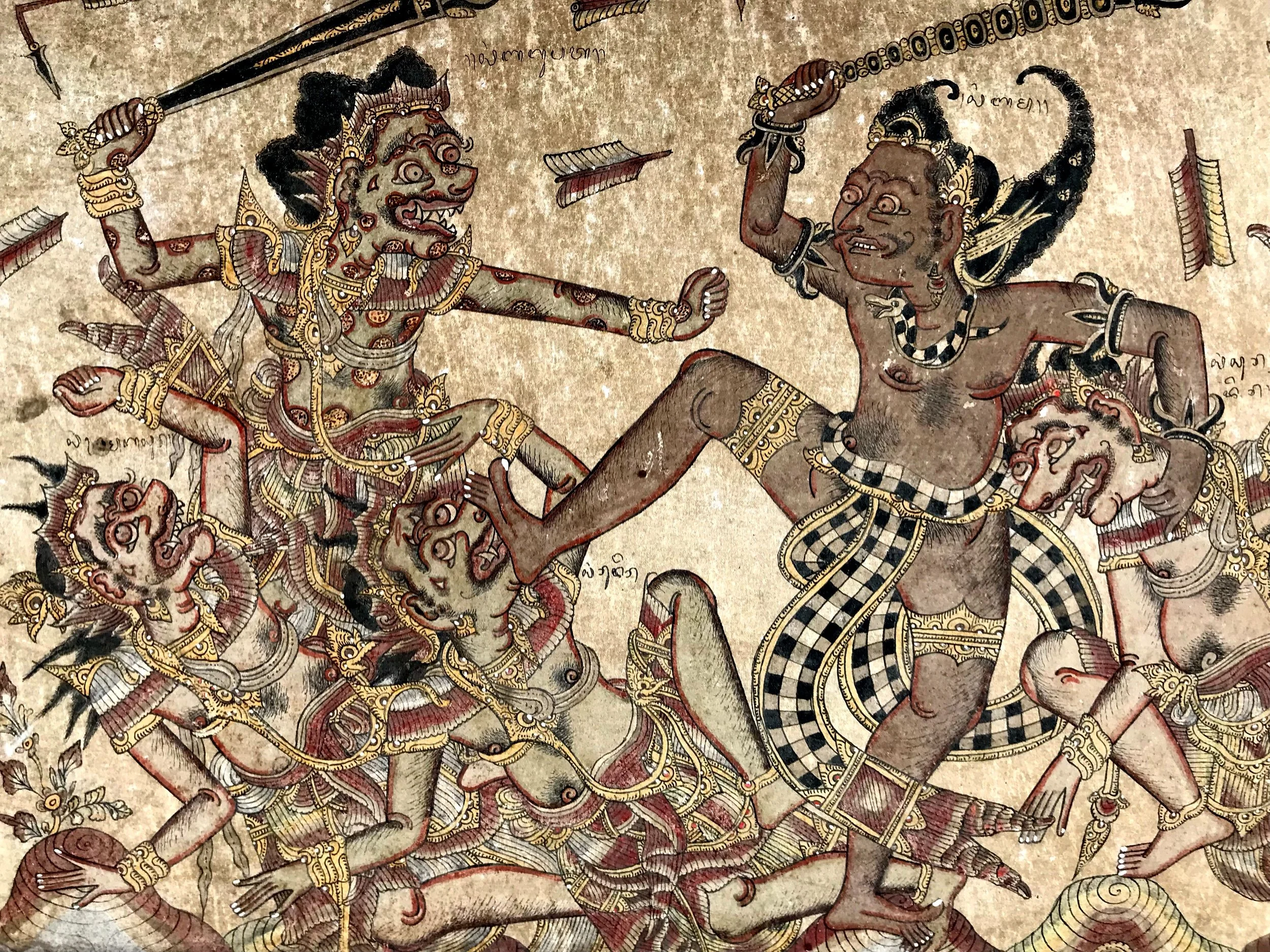

“Many Hindu gods have skin glowing in hues beyond the human — deep blue for cosmic infinity, gold for radiance, green for life itself.

Multiple arms signal their boundless power, each hand holding a weapon, tool, lotus or blessing. ”

Some are worshipped as supreme in their own right; others are venerated as avatars, or incarnations, of the same cosmic force. You might see the same god in wildly different guises — gentle one moment, ferocious the next — depending on the story being told. And while millions of forms may exist in theory, a core roster of perhaps 20 or so names dominates the Hindu spiritual and cultural imagination.

Here, we’ve gathered the most prominent Hindu gods and goddesses. You’ll meet gods who ride lions, owls, bulls and even mice; goddesses who create, nurture and destroy; and divine heroes whose epics have shaped centuries of art, music and philosophy.

While each deity is unique in their own way, you’ll notice certain recurring themes that mark their divinity. Many are crowned with halos of light, their skin glowing in hues beyond the human — deep blue for cosmic infinity, gold for radiance, green for life itself. Multiple arms signal their boundless power, each hand holding a weapon, tool, lotus or blessing. They are adorned with jewels and garlands, their forms draped in silks that ripple like clouds or sunlight. At their side waits a faithful vahana, an animal mount whose nature mirrors the god’s own — be it the fierce lion, the graceful swan or the humble mouse. These shared elements form a visual language of the divine, instantly recognizable across temples, paintings and stories.

Whether you’re new to Hindu mythology or deepening your familiarity, consider this your guided tour of the celestial VIP list.

Annapurna

The goddess who feeds the world

Domain: Nourishment, food, abundance, hospitality

Symbolism: Golden ladle for the act of serving, bowl of food for sustenance, grain for prosperity, kitchen hearth for the warmth of home

Appearance: Annapurna’s beauty is that of comfort — the kind that draws you in from the cold and fills your bowl before you can ask. Her skin glows with the warmth of an autumn harvest, and her dark hair falls in glossy waves beneath a golden crown. She wears a crimson sari edged in gold, the color of ripened grain in the sun, and jewels that glint like the first sparks from a cooking fire. In one hand, she holds a golden ladle; in the other, a bowl brimming with food, the eternal promise that no soul will go hungry in her presence.

Mount/Vahana: None traditionally. She’s often depicted seated in a kitchen or temple setting.

Mythological role: Annapurna is a form of Parvati, born to remind even Shiva that life cannot be lived on renunciation alone. When Shiva once declared that the world was an illusion — including the need for food — she disappeared, and the earth grew barren. Only when hunger touched every being did Shiva seek her out. Finding her in Varanasi, he humbled himself, and she served him a meal with her own hands. From then on, she became the goddess of nourishment, the one who teaches that the spiritual and the physical are inseparable.

Consort and family: As a form of Parvati, she’s the wife of Shiva and mother of Ganesha and Kartikeya.

Associated festivals: Annapurna Jayanti (celebrating her birth), observed mainly in northern India

Worship and significance: Devotees seek Annapurna’s blessings for a plentiful harvest, a stocked kitchen and the generosity to feed others. Her temples often serve prasada (sanctified food) to all who come, without question of wealth or status.

Fascinating fact: The Annapurna temple in Varanasi is one of the few where food — rather than flowers or incense — is the primary offering.

Brahma

The creator, architect of the universe

Domain: Creation, knowledge, the cosmic order

Symbolism: Four heads gazing in all directions, each reciting one of the Vedas; a water pot holding the seed of life; the lotus, symbol of the universe’s unfolding

Appearance: Imagine an elderly yet ageless figure, his beard as white as the snows of the Himalayas, his skin glowing with the faint blush of dawn. Brahma wears robes the color of the rising sun — deep pinks and reds, shimmering with gold threads that catch the light. His four heads turn in unison, surveying all corners of the cosmos. Each face holds a calm, wise expression, as if they’ve already seen all possible futures. In one hand, he holds the Vedas, the sacred knowledge of the universe; in another, a mala (prayer beads) that he uses not for devotion, but for counting the endless cycles of creation and destruction.

Mount/Vahana: A swan named Hamsa, symbolizing discernment and wisdom. The swan is said to be able to separate milk from water, just as Brahma discerns truth from illusion. In art, Hamsa often glides beside him, wings lifted as if in mid-takeoff, ready to carry him across the endless skies.

Mythological role: Brahma’s story begins in a lotus — but not just any lotus. It sprouted from the navel of another god, Vishnu, as he lay upon the cosmic ocean, and from that lotus, Brahma emerged. He became the craftsman of reality, shaping the heavens, Earth and all beings. And yet, despite his monumental role, Brahma is one of the least-worshipped gods in Hinduism. Myth has it this is due to a curse: After a quarrel with Shiva and an act of deceit to prove his supremacy, Brahma lost the right to have temples dedicated to him. Today, there are only a handful of temples in the world where he is the main deity, the most famous being in Pushkar, Rajasthan. He is, though, often found inside spirit houses on Bali.

Consort and family: Saraswati, goddess of wisdom, is his wife and creative partner — her music and intellect inspiring his act of creation.

Associated festivals: Brahmotsavam in Tirupati carries his name but actually honors Vishnu; Kartik Purnima in Pushkar celebrates him directly.

Worship and significance: As the origin point of creation, Brahma represents knowledge, beginnings and the birth of ideas — whether that’s the universe itself or the spark of inspiration in a human mind.

Fascinating fact: Each of Brahma’s days lasts 4.32 billion human years. At the end of one of his “days,” the universe dissolves into the cosmic ocean, only to be re-created when he awakens. In other words, even the universe has a bedtime.

Chandra

The moon god, keeper of time and tides

Domain: The moon, time, fertility, the mind and the life-giving elixir soma

Symbolism: The luminous crescent moon, the night sky strewn with stars, a chariot pulled by antelopes, and the cool radiance that soothes the earth after the heat of day

Appearance: Picture the night as a velvet canopy, deep navy and speckled with pinpricks of silver light. Cutting through that darkness is Chandra’s chariot — sleek, gleaming, and drawn by a team of pure white antelopes. Chandra has a youthful face, his skin glowing with the pale luminescence of moonlight reflected on water. His black hair flows beneath a crown that holds a crescent moon, its tips like delicate silver horns. Draped in garments of pearl white and soft blue, he carries a lotus, symbol of purity, and his eyes have a dreamy calm that mirrors the gentle pull he exerts on the tides.

Mount/Vahana: A shining chariot drawn by 10 white antelopes (or, in some traditions, horses with antelope heads). The choice of mount reflects agility, swiftness and the moon’s ability to traverse the heavens with grace.

Mythological role: Chandra’s presence in the sky is more than decoration; he is the very heartbeat of time in the Hindu calendar. The waxing and waning of his light marks the rhythm of festivals, rituals and agricultural cycles. But his myths are not without drama. In one tale, Chandra married the 27 daughters of Daksha, the starry “nakshatras” or lunar mansions, but favored one, Rohini, above the rest. His neglect angered Daksha, who cursed him to fade away. This curse explains the moon’s waning phase — until the gods intervened to let him regain his strength, creating the cycle of waxing and waning we see each month.

Chandra is also tied to the sacred drink soma — in some traditions, he is soma personified, the elixir that nourishes gods and mortals alike. When he disappears at the new moon, it is said he is being “drunk” by the gods, only to be reborn and replenished.

Consort and family: Married to the 27 nakshatras, with Rohini as his most beloved. In some myths, he fathers Budha (the planet Mercury, not to be mistaken with the Buddha) with the goddess Tara, sparking a celestial scandal.

Associated festivals: Karva Chauth, where married women fast until they see the moon; Sharad Purnima, celebrating Chandra’s brightest, most benevolent light of the year.

Worship and significance: Chandra governs the mind and emotions in Vedic astrology, influencing calmness, creativity and romance. He is called upon for mental clarity, fertility blessings and the soothing of emotional storms.

Fascinating fact: While most gods have one vahana, Chandra’s chariot is pulled by not one but 10 antelopes, a detail that adds a touch of otherworldly strangeness (and a nod to Santa Claus) to his midnight ride.

Durga

The invincible mother, warrior goddess of cosmic balance

Domain: Protection, destruction of evil, strength, righteousness, the embodiment of shakti (divine feminine power)

Symbolism: Ten arms each bearing a weapon from the gods, the lion or tiger as her mount, and the serene smile of a warrior who knows the battle is already won

Appearance: The horizon burns with gold and crimson light, the air trembling as the roar of a lion cuts through the clamor of war. On its back sits Durga — radiant, unflinching, crowned with a gleaming diadem that catches the sun like fire. Her skin glows like molten gold, and her eyes are wide and steady, reflecting the calm at the heart of a storm. Each of her 10 arms moves with divine precision: One looses an arrow, another swings a sword, another raises a conch to rally her allies. Each weapon was a gift from a god, entrusted to her when they realized no male deity could defeat the demon Mahishasura.

Mount/Vahana: A lion or tiger, symbolizing power, fearlessness and the ferocity needed to destroy evil. In many images, her mount is mid-leap, claws bared, charging into battle beside her.

Mythological role: Durga’s most famous tale is her battle with Mahishasura, a shape-shifting buffalo demon who could not be killed by man or god. For nine days and nights, she fought him, her weapons flashing like lightning. On the 10th day, she struck the final blow, the demon collapsing at her feet. This victory is celebrated as Vijayadashami (the Day of Victory), and the nine nights of battle as Navratri. But Durga isn’t just a warrior — she’s also a compassionate mother and a guardian of the innocent, protecting the world from forces that disrupt cosmic order.

Consort and family: Considered an aspect of Parvati, wife of Shiva, and mother to Ganesha and Kartikeya. In her warrior form, she stands apart, representing the untamed energy that even the gods must revere.

Associated festivals: Durga Puja, Navratri, Vijayadashami — all filled with dancing, music and processions of her image returning to the water from which she came.

Worship and significance: Durga is called upon for courage, protection and the strength to face seemingly insurmountable challenges. Her image is often placed at thresholds or in vehicles as a ward against danger.

Fascinating fact: In many depictions, Durga is shown skewering Mahishasura at the exact moment he shifts from buffalo to human form — symbolizing her mastery over chaos itself, striking at the perfect moment when the enemy is most vulnerable.

Ganesha

The granter of boons, remover of obstacles, lord of beginnings and wisdom

Domain: Wisdom, intellect, new ventures, success, remover of obstacles both physical and spiritual

Symbolism: Elephant head (wisdom and memory), large ears (listening deeply), small eyes (focus), a curved trunk (adaptability), broken tusk (sacrifice for knowledge), a sweet dumpling known as modak (reward of spiritual pursuit)

Appearance: A figure that makes everyone smile. Ganesha sits with the casual ease of someone who has already solved your problems before you’ve spoken them aloud. His elephant head is grand yet gentle, with eyes that crinkle in amusement and ears spread like open hands, ready to catch every prayer. His skin is often a warm pink or golden hue, adorned with rich silks in reds and yellows, gold bangles chiming softly at his wrists. One hand raises in blessing; another holds a sweet modak, its conical shape a symbol of spiritual rewards. Another hand may wield an axe, to cut away attachments, while the fourth carries a rope, to draw devotees closer to their goals.

Mount/Vahana: A small, humble mouse named Mushika. At first glance, it seems absurd — an enormous god riding a tiny creature — but the symbolism is deliberate. The mouse represents desires, which can gnaw endlessly if unchecked. Ganesha, in riding it, shows mastery over impulses, and the ability to reach even the smallest corners of the mind where obstacles hide.

Mythological role: Ganesha’s origin stories are as colorful as his depictions. In the most popular version, Parvati fashioned him from the turmeric paste she used for bathing, breathing life into the boy to guard her privacy. When Shiva, her husband, returned and found this unknown child blocking his way, he beheaded him in a fit of divine rage. Realizing his mistake, Shiva replaced the head with that of the first creature he found — an elephant — and bestowed upon Ganesha the role of guardian of thresholds, beginnings and new journeys.

He appears in countless tales, often outwitting gods and demons alike with his quick thinking. One famous story tells how he won a race around the world against his brother Kartikeya by circling his parents, declaring that they were his whole world — a victory earned through wisdom, not speed.

Consort and family: Son of Shiva and Parvati, brother to Kartikeya. In some traditions, married to Siddhi (spiritual power) and Buddhi (intellect).

Associated festivals: Ganesh Chaturthi: a 10-day celebration where clay idols of Ganesha are immersed in water, symbolizing both his arrival and return to the divine realm.

Worship and significance: Ganesha is invoked at the start of all endeavors — whether building a temple, writing a book or opening a shop. His image is often placed above doorways, on business ledgers and on the dashboards of cars, ensuring smooth beginnings and safe journeys. As Vighnaharta, the remover of obstacles, and Varada, the granter of boons, he is the god to whom devotees turn when seeking success, blessings and protection.

Fascinating fact: The broken tusk has several explanations. In one, Ganesha broke it off to use as a quill for writing the epic Mahabharata as the sage Vyasa dictated it, agreeing never to stop until the work was complete. The sacrifice turned a blemish into an eternal symbol of devotion to knowledge.

Hanuman

The monkey god, embodiment of strength and devotion

Domain: Courage, loyalty, protection, selfless service

Symbolism: The gada (mace) for strength, the mountain he carries for resourcefulness, and his open chest revealing the images of Rama and Sita — a literal heart of devotion

Appearance: A figure with the face of a monkey but the stance of a seasoned warrior — broad shoulders, a long curling tail, eyes full of determination. Hanuman’s skin is often rendered in shades of deep gold or copper, his muscles taut with power earned through ascetic discipline. He wears a simple dhoti, sometimes red, sometimes saffron, with golden ornaments that catch the light as he moves. His most striking image is not when he wields his mace or leaps across the sea, but when he tears open his chest to reveal the divine couple Rama and Sita glowing inside — proof that they live in his heart.

Mount/Vahana: None in the traditional sense; Hanuman’s own supernatural strength, speed, and ability to leap vast distances make him his own transport. In art, he’s often shown soaring through the air, wind whipping through his fur.

Mythological role: Hanuman’s story is woven tightly into the Ramayana. Born to Anjana and blessed by the wind god Vayu, he displayed superhuman powers from childhood — once leaping to catch the sun, mistaking it for a fruit. As an adult, he becomes the devoted ally of Rama in the quest to rescue Sita from Ravana. His feats include burning the city of Lanka with his flaming tail, carrying an entire mountain of herbs to heal Lakshmana, and crossing oceans in a single bound. Yet for all his power, Hanuman is known for humility — he never seeks glory for himself, only the success of Rama’s mission.

Consort and family: Celibate by choice, devoting all his energy to service and devotion. Son of Anjana and the wind god Vayu.

Associated festivals: Hanuman Jayanti, celebrated with recitations of the Hanuman Chalisa and offerings of sindoor (vermilion powder).

Worship and significance: Hanuman is called upon for strength in adversity, courage in the face of danger, and protection from evil influences. Temples dedicated to him often have devotees chanting his name or circling the shrine for blessings.

Fascinating fact: Hanuman’s name means “disfigured jaw” — a reference to the childhood incident where Indra struck him with a thunderbolt when he tried to grab the sun, injuring his jaw but also awakening his divine powers.

Indra

King of the heavens, wielder of the thunderbolt

Domain: Rain, storms, war, kingship, protection of cosmic order (ṛta)

Symbolism: The Vajra (thunderbolt) for irresistible power, Airavata the elephant for strength and majesty, rain clouds for life-giving abundance, the rainbow for divine promise

Appearance: Indra stands tall and broad-shouldered, the bearing of a warrior-king in every line of his frame. His skin glows with the vitality of fresh rain on sunlit stone, and his eyes flash with the quicksilver of lightning. A golden crown rests on his brow, studded with gems that mirror the colors of the sky — sapphire for the clear day, opal for the gathering storm. Draped in silks the color of storm clouds, he carries the Vajra, forged from the bones of the sage Dadhichi, a weapon that can shatter even the mightiest foe.

Mount/Vahana: Airavata, the great white elephant, vast as a mountain and crowned with four tusks. His steps shake the earth, and from his trunk he sprays water that feeds the clouds, heralding the monsoon.

Mythological role: Indra is the king of the Devas and ruler of Svarga, the heavenly realm. In the Vedic age, he was the supreme god, the bringer of rain and the breaker of drought. His most famous legend tells of his battle with Vritra, the serpent-demon who had imprisoned the world’s waters. Riding Airavata and wielding the Vajra, Indra struck Vritra down, freeing the rivers and restoring life to the land. Later myths show him as both hero and flawed figure — brave in battle, quick to defend the gods, yet prone to pride and desire.

Consort and family: Married to Shachi (also called Indrani), queen of the heavens. Son of the sky-god Dyaus and the dawn goddess Prithvi in some accounts, though genealogies vary.

Associated festivals: While Indra is less central in modern Hindu worship, he’s honored in certain regional festivals, such as Indra Jatra in Nepal, which celebrates him as the god of rain and the harvest.

Worship and significance: Once the chief deity of the Rigveda, Indra’s prominence has shifted over time. But he remains a powerful symbol of leadership, protection and the life-giving force of rain. Farmers and warriors alike have invoked his name for victory and survival.

Fascinating fact: In some Balinese traditions, Indra is seen as a mediator between gods and humans — a role that has parallels in the island’s legends of Barong and Rangda, the eternal dance of protection and destruction.

Kali

The fierce mother, devourer of time, destroyer of illusions

Domain: Destruction of evil, liberation, transformation, time, empowerment

Symbolism: Garland of severed heads (knowledge gained through ego’s destruction), skirt of severed arms (detachment from action), lolling red tongue (shock and raw power), weapons and a severed demon head in her hands (victory over darkness)

Appearance: Kali does not arrive quietly. She bursts into the battlefield like a storm let loose, her skin the color of midnight, absorbing all light. Her hair streams wild and unbound, a living halo of chaos, and her eyes blaze like twin suns at the moment of apocalypse. Around her neck hangs a grisly garland — fifty severed heads, each representing a Sanskrit letter, a reminder that all speech and creation eventually dissolve into silence.

Her skirt is a belt of severed arms, trophies from foes, but also a symbol that the fruits of action belong to the divine, not to the ego. In two hands she holds weapons: a sword and a trident; in another, she clutches the freshly severed head of a demon, its blood still dripping onto the ground. Her other hands are extended in gestures of blessing and reassurance, an unsettling reminder that the one who destroys also protects.

Mount/Vahana: None in her most iconic form — Kali’s arrival is so sudden and overwhelming that she needs no mount. In some regional depictions, she is associated with jackals or rides upon the corpse of a demon, symbolizing her mastery over death itself.

Mythological role: Kali’s most famous appearance comes in the battle against the demon Raktabija. Each drop of his blood that hit the earth produced another demon, making him nearly impossible to kill. Kali’s solution was both brilliant and terrifying: she tore through the battlefield, drinking his blood before it could touch the ground, consuming him entirely.

But her ferocity once threatened to tip into total annihilation. In a victory frenzy, she rampaged across the world until Shiva lay down in her path. Stepping on him, she realized what she was doing — her tongue darting out in shock. That moment is immortalized in her most famous pose: foot on Shiva’s chest, tongue out, eyes wide, the destroyer stopped by compassion.

Consort and family: Considered a form of Parvati, consort of Shiva, though in her aspect as Kali she often acts alone.

Associated festivals: Kali Puja, coinciding with Diwali in Bengal; Navratri in her fierce aspect.

Worship and significance: Kali is worshipped not for gentle blessings, but for transformation — she burns away illusions, attachments, and fears. Devotees come to her to destroy what is holding them back, knowing the process may be as fierce as she is.

Fascinating fact: In Tantric traditions, Kali is not feared but embraced as the ultimate reality — the womb and the tomb, creation and destruction in one. Her darkness is not evil, but the infinite void from which all life emerges and to which it returns.

Kartikeya (aka Murugan)

The youthful warrior, commander of the divine army

Domain: War, victory, wisdom, leadership, guardianship of dharma

Symbolism: Spear (vel) for piercing ignorance, peacock for pride mastered, rooster emblem for dawn and vigilance.

Appearance: Kartikeya is the god of youth and vigor, and it shows in every depiction. He’s sometimes depicted with six faces (a nod to his birth story, below), though most often as a youth with a single handsome face. His skin glows like burnished gold, his features sharp and confident, with eyes that flash like drawn steel. His hair falls in dark waves past a diadem encrusted with rubies, and his body is draped in fine silks the color of peacock feathers. Across his chest gleams a golden chain, and in one hand he holds the vel, a spear so perfectly balanced it seems to float in his grasp.

The vel was a gift from his mother Parvati, forged from her own shakti (divine power), and it never misses its mark. In his other hand he may carry a small banner emblazoned with a rooster, whose crowing heralds the light that drives away the night’s dangers.

Mount/Vahana: A regal peacock named Paravani, feathers iridescent with blues and greens that shimmer like oil on water. The peacock is a symbol of beauty and vanity mastered — its sharp talons and fierce beak a reminder that elegance does not preclude ferocity. In many depictions, the peacock tramples a serpent beneath its claws, representing the conquest of harmful desires and ego.

Mythological role: Kartikeya was born for battle. When the demon Tarakasura could only be slain by Shiva’s son, the gods sought to bring Shiva and Parvati together. From their union came six sparks of fire, carried by the river Ganga to a lotus pond, where they became six infants. The celestial nymphs known as the Krittikas nurtured them, and when Parvati embraced all six at once, they merged into one child with six faces — a tradition that gave him an alternate name Shanmukha, “Six-Faced One.”

He grew to be the general of the gods’ army, leading them to victory against Tarakasura. In South India, he is celebrated as Murugan, the patron of Tamil culture and poetry, embodying both the scholar and the warrior.

Consort and family: Son of Shiva and Parvati, brother to Ganesha. In some traditions, he’s married to Valli and Devasena.

Associated festivals: Thaipusam, Skanda Shashti, Panguni Uthiram — celebrated with grand processions, kavadi offerings such as pots of milk, and feats of devotion.

Worship and significance: Kartikeya is invoked for courage, clarity and success in competition. In Tamil Nadu, devotees climb hills barefoot to reach his temples, mirroring the god’s own journey to conquer the heights of battle.

Fascinating fact: In some depictions, Kartikeya’s peacock mount is shown turning its head to watch him closely, as if taking silent instruction — a visual metaphor for the disciplined control of power and pride.

Krishna

The divine lover, cowherd and protector of dharma

Domain: Love, compassion, joy, divine play (lila), protection of the righteous

Symbolism: Flute for the music of the soul, peacock feather for beauty and grace, cows for abundance and gentleness, yellow garments for the light of divinity

Appearance: Krishna’s beauty is the kind that makes time pause. His skin is the deep blue of monsoon clouds, luminous and alive, as if it holds the promise of rain. His eyes are dark and playful, holding secrets he’ll never tell outright; instead, he lets them slip in song. Around his head rests a crown woven with fresh peacock feathers, shimmering emerald and sapphire. He wears a yellow pitambara (silken dhoti) that moves like sunlight caught in a breeze.

He holds his flute to his lips, coaxing a melody so sweet that cows stop grazing, rivers change their course to listen, and hearts — even those hardened by pride — begin to soften. At his feet, the gopis (cowherd girls) stand transfixed, drawn not just to his beauty but to the boundless love it reflects.

Mount/Vahana: None. Krishna’s life is pastoral; he walks among cows in the town of Vrindavan, accompanied by the sound of ankle bells and the laughter of companions. In battle, he drives the warrior Arjuna’s chariot as a guide rather than a mounted warrior.

Mythological role: Krishna’s story spans from playful trickster to statesman and philosopher. As a child, he stole butter from every household, earning the nickname Makhan Chor (“Butter Thief”), and once lifted the massive Govardhan Hill on his finger to shelter villagers from a storm sent by the rain god Indra. As an adult, he becomes the moral compass and strategist of the Mahabharata, delivering the Bhagavad Gita to Arjuna on the eve of battle: a discourse on duty, devotion and the eternal soul that has shaped Hindu philosophy for millennia.

But Krishna is also the god of lila — divine play. His romances with Radha and the gopi cowherd girls work also as metaphors for the soul’s yearning for union with the divine.

Consort and family: Beloved of Radha; in later life, married to Rukmini and other queens of the legendary city of Dwaraka. Son of Vasudeva and Devaki, raised by Nanda and Yashoda.

Associated festivals: Janmashtami (his birth), Holi (the festival of colors, recalling his playful smearing of colors on Radha)

Worship and significance: Krishna is worshipped as the supreme personality of godhead in many traditions. Devotees seek him for joy, love and guidance, whether in the innocence of childhood games or the gravity of moral decisions.

Fascinating fact: Krishna’s flute, called Murali, gets its power from the divine breath that flows through it, reminding devotees that we are instruments for the divine will when we let go of ego.

Lakshmi

The radiant goddess of fortune, beauty and abundance

Domain: Wealth, prosperity, good fortune, fertility, spiritual abundance

Symbolism: Lotus flowers for purity and spiritual awakening, gold coins flowing from her palms for prosperity, elephants for royal authority and generosity

Appearance: Lakshmi is the very embodiment of grace — a vision bathed in light as if she herself is the sunrise breaking over still waters. Her skin glows with a golden warmth, and she wears a red sari embroidered with gold thread, the fabric rippling like firelight. Each movement is deliberate and fluid, like the gentle opening of a lotus.

In most depictions, she stands or sits upon a blooming lotus floating on the cosmic ocean, the petals cupping her like a throne. Two of her four hands hold lotuses, their long stems rising gracefully; the other two extend in blessing, one palm open in reassurance, the other pouring an endless stream of gold coins that pile into shimmering mounds at her feet. The air around her is alive with elephants spraying water from golden vessels, symbols of strength and auspiciousness.

Mount/Vahana: An owl, symbolizing wisdom and the ability to see through darkness. Though rarely emphasized in modern depictions, the owl reminds devotees that wealth without wisdom can lead to downfall — Lakshmi’s blessings must be balanced with discernment.

Mythological role: Lakshmi emerged fully grown from the churning of the cosmic ocean (Samudra Manthan), radiant and carrying a lotus. The gods and demons had worked together to churn the ocean for the nectar of immortality, but it was Lakshmi’s appearance that became the crowning blessing of their labor. She chose Vishnu as her eternal consort, and from then on accompanied him in every incarnation — as Sita to his Rama, as Rukmini to his Krishna.

True prosperity, she teaches, includes health, love, knowledge and spiritual growth. In some stories, she tests the worthiness of those who seek her, disappearing from households where greed and injustice reign.

Consort and family: Wife of Vishnu; in his earthly incarnations, she is born alongside him.

Associated festivals: Diwali, especially Lakshmi Puja, when homes are cleaned, lit with lamps, and decorated to welcome her

Worship and significance: Lakshmi is one of the most widely worshipped deities in Hinduism. Businesses open their books in her name, households pray to her for stability, and farmers seek her blessing for fertile fields.

Fascinating fact: In southern India, Lakshmi is sometimes depicted in eight forms known as Ashtalakshmi, each representing a different type of wealth — from material prosperity to courage, fertility and knowledge.

Meenakshi

The warrior-queen and fish-eyed goddess of Madurai, one of the oldest continuously inhabited cities in the world

Domain: Fertility, prosperity, protection of Madurai, righteous rule

Symbolism: Green skin for life and abundance, fish-shaped eyes for watchfulness and grace, crown for sovereignty, parrot for love and divine speech

Appearance: Meenakshi’s beauty is unlike any other — her skin glows a vivid green, like new rice shoots after the rain, a sign of the fertile abundance she brings. Her almond-shaped eyes, long and luminous, are said to resemble fish — always open, never blinking, guarding her people as a fish watches over its young. She wears royal silks in deep magenta and gold, and a towering crown studded with rubies and emeralds. In one hand she holds a bouquet of lotuses; in the other, a parrot perches, its feathers bright as new leaves, whispering divine secrets into her ear.

Mount/Vahana: Often depicted standing rather than riding, but sometimes shown with a parrot or lion as her companion.

Mythological role: Born to the king and queen of Madurai after a divine promise from the gods, Meenakshi entered the world with three breasts — a sign she was destined for greatness. Prophecy foretold that the extra breast would vanish when she met her future husband. A fierce warrior, she led armies to conquer neighboring lands, never defeated in battle. When she encountered Shiva in his form as Sundareshwarar, her third breast disappeared, and they were wed in a grand ceremony that united divine power with royal rule.

Consort and family: Married to Shiva (as Sundareshwarar) and worshipped alongside him. Considered an incarnation of Parvati

Associated festivals: Meenakshi Thirukalyanam (her celestial wedding), Chithirai Festival in Madurai

Worship and significance: Meenakshi is the heart of Madurai’s spiritual life, enshrined in the colossal Meenakshi Amman Temple, whose gopurams (gateway towers) rise like jeweled mountains over the city. She is both a tender mother and an unflinching protector, blessing devotees with prosperity while defending her city with warrior strength.

Fascinating fact: In Tamil tradition, parrots are symbols of eloquence and divine love, repeating sacred mantras and carrying messages between the human and divine realms.

Parvati

The gentle mother, devoted wife and wellspring of divine energy

Domain: Love, fertility, marital devotion, spiritual power (shakti)

Symbolism: Lotus for purity, mirror for self-knowledge, red garments for passion and vitality, and her many forms — from nurturing Annapurna to fierce Durga and terrifying Kali.

Appearance: Parvati’s beauty is the quiet kind — like a lamp’s steady flame, constant and unwavering. Her skin glows with the warm bronze of sunlit earth, and her large, compassionate eyes seem to see through pretenses straight to the heart. She wears a red sari edged in gold, its color speaking of both love and strength, and her long black hair is often braided and adorned with fresh flowers. A crescent moon, borrowed from her husband Shiva, sometimes gleams in her hair, a sign of their eternal bond.

When she sits beside Shiva atop Mount Kailash, she radiates the warmth that softens his ascetic severity. Yet within that serenity is the power of all the goddesses — the potential to become the lion-riding Durga or the dark, storm-eyed Kali when the world needs defending.

Mount/Vahana: Lion or tiger, representing courage, power and her latent warrior nature. While gentle in her most common form, her vahana is a reminder that she carries within her the force to vanquish evil.

Mythological role: Parvati’s love story with Shiva is one of devotion and persistence. Born as the daughter of the mountain king Himavan, she fell in love with Shiva, the god of destruction, who was lost in deep meditation. Her devotion was tested by years of austerity and trials, until Shiva finally accepted her as his wife. Together, they are the divine couple whose union balances ascetic withdrawal and earthly engagement.

As a mother, Parvati is nurturing yet fiercely protective — the one who fashioned Ganesha from her own body and defended her privacy against even Shiva himself. Her many forms represent the full spectrum of the feminine divine: the giver of food as Annapurna, the destroyer of demons as Durga, the liberator as Kali.

Consort and family: Wife of Shiva, mother of Ganesha and Kartikeya

Associated festivals: Teej (celebrating marital devotion), Navratri (in her various forms)

Worship and significance: Parvati is worshipped by women for marital happiness, fertility and family well-being. She’s also invoked for strength and balance, as she embodies the union of compassion and power.

Fascinating fact: In one tale, Parvati playfully covered Shiva’s eyes from behind, unaware that without his gaze, the universe was plunged into darkness. To restore the balance, she transformed into her radiant golden form, Mahagauri, bringing light back to the cosmos.

Radha

The eternal beloved, embodiment of devotion

Domain: Divine love, spiritual longing, union with the divine

Symbolism: Lotus for purity of heart, veil for modesty, pastoral settings for the soul’s journey, and her inseparable connection to Krishna as the soul is to a deity

Appearance: Radha’s beauty is the kind that pulls at the heart — not through grandeur, but through the quiet ache of longing. Her skin is luminous, her eyes large and dark, holding both joy and the weight of separation. She wears a flowing lehenga in deep crimson or midnight blue, adorned with golden embroidery that catches the sun. A long veil frames her face, shifting with the breeze as she moves through the meadows of the town of Vrindavan.

In art, she’s almost always shown glancing toward Krishna, her posture poised between approach and retreat. Her hands may cradle a garland of fresh jasmine meant for him, or a pot of butter she will let disappear into his thieving hands. The landscape around her — the river Yamuna, the blossoming kadamba trees — seems to bend subtly toward her, as if drawn to the devotion she radiates.

Mount/Vahana: None. Radha moves through the pastoral world on foot, walking the same cow-trodden paths as Krishna, her presence transforming the fields and forests into sacred space.

Mythological role: Radha’s love for Krishna is the gold standard of devotion in Hinduism — selfless, unbound by social convention and beyond the reach of time. Though she’s not mentioned in the earliest scriptures, later devotional literature, especially in the Bhagavata Purana and the poetry of Jayadeva’s Gita Govinda, elevates her to demigod status. She’s the human soul (jivatma) yearning for reunion with the supreme soul (paramatma), her longing for Krishna standing in for humanity’s longing for the divine.

Their relationship is one of pure connection. Even when separated, Radha feels Krishna’s presence in every breath, and her yearning is considered even more powerful than the joy of union — for it keeps the heart in constant remembrance of the beloved.

Consort and family: Beloved of Krishna; often depicted as his spiritual counterpart rather than a worldly consort

Associated festivals: Rasa Lila reenactments during Holi and Janmashtami; Radhashtami, celebrating her birth

Worship and significance: Radha is worshipped alongside Krishna in many temples, especially in the Gaudiya Vaishnava tradition, where she’s revered as the source of Krishna’s joy. Devotees seek her grace to cultivate pure, unconditional love for the divine.

Fascinating fact: In some traditions, Radha is considered an incarnation of Lakshmi, born to be Krishna’s eternal companion. Her name is often invoked first in chants — “Radhe Krishna” — as if to approach the beloved through the one who knows him best.

Rama

The noble prince, upholder of dharma, the right way of living

Domain: Virtue, moral duty, justice, kingship, protection of the righteous

Symbolism: Bow and arrow for readiness and skill in battle, blue skin for divine origin, simple yet regal garments for humility in leadership

Appearance: Rama stands with the quiet authority of a man who knows his strength and has no need to boast. His skin is the rich blue of a twilight sky, his posture upright and composed. He wears a golden crown that catches the sun, yet his garments are simple — the saffron robes of an exile rather than the ornate silks of a king. Across his shoulder rests a quiver of arrows, and in his hand, his bow is always ready, a natural extension of himself rather than an ornament.

His expression is calm, even in the face of war. There’s a gentleness in his gaze that belies the steel in his resolve — a leader whose strength lies as much in compassion as in martial skill. In art, he is often shown alongside Sita, Lakshmana and Hanuman, forming the ideal vision of a harmonious household and righteous rule.

Mount/Vahana: Rama has no permanent animal mount. In the Ramayana, he travels on foot, by chariot, or with the aid of allies like Hanuman. His lack of a vahana underscores his humanity — the idea that righteousness and divine purpose can be lived out in the mortal world without supernatural crutches.

Mythological role: Rama’s life is told in the epic Ramayana, where he is born as the prince of Ayodhya, the seventh avatar of Vishnu, sent to destroy the demon king Ravana. When his stepmother’s scheming leads to his exile, he accepts the decree without anger, honoring his father’s word above his own comfort. For 14 years, he roams the forests with Sita and his younger brother, Lakshmana, defending sages and villages from demons.

The defining trial of his life comes when Sita is abducted by Ravana. With the help of Hanuman and an army of vanaras (monkey warriors), Rama wages war on the island kingdom of Lanka, eventually killing Ravana and restoring order. His reign after returning to Ayodhya is remembered as Rama Rajya — an era of justice, peace and prosperity.

Consort and family: Husband of Sita, brother to Lakshmana, Bharata and Shatrughna. Son of King Dasharatha and Queen Kaushalya

Associated festivals: Rama Navami (his birth), Diwali (marking his return to Ayodhya

Worship and significance: Rama is revered as the perfect man — a warrior without cruelty, a ruler without arrogance, a husband without neglect. Devotees seek his blessing for moral clarity and the strength to act in accordance with dharma, even when it is costly.

Fascinating fact: In some folk retellings, Rama’s bow was so powerful that only he could lift it — he proved his worth to marry Sita by stringing it with effortless grace, a feat no other suitor could manage.

Saraswati

The serene muse, goddess of wisdom, music and the arts

Domain: Knowledge, learning, speech, music, poetry, truth

Symbolism: Veena (lute) for harmony and creativity, white lotus for purity of mind, flowing river for the unending stream of wisdom, swan for discernment

Appearance: Saraswati is the embodiment of clarity and calm — a vision in white, untouched by the dust of greed or the heat of passion. Her skin is pale and luminous, her long hair flowing like dark silk down her back. She wears a simple white sari with a golden border, the fabric so light it moves like water when she shifts. A garland of fresh jasmine hangs around her neck, and her forehead is marked with the tilak of concentration.

In her hands, she cradles the veena, each note she plays carrying the resonance of cosmic truth. A white lotus blooms beneath her feet, symbolizing the mind’s ability to rise unstained from the muddy waters of ignorance. Behind her, the gentle current of a river often winds through the scene — a reminder of her origin as the goddess of the Saraswati River, whose sacred waters nourished the Vedic civilization.

Mount/Vahana: Swan (hamsa), representing the ability to separate truth from falsehood. In some depictions, she rides a graceful peacock, whose beauty is balanced by its vigilance against snakes — a metaphor for guarding wisdom against corruption.

Mythological role: Saraswati is said to have been present at creation itself, when Brahma called upon her to bring order to the chaos. With her wisdom, she gave names to all things, creating speech and language. She is the inspiration behind poetry, the patron of scholars, and the divine voice that flows through musicians’ hands.

Her presence is subtle yet essential — in mythology, gods and mortals alike call upon her before embarking on intellectual or creative endeavors. Without Saraswati, knowledge remains dormant; with her, it becomes luminous and transformative.

Consort and family: In some traditions, consort of Brahma; in others, she stands alone as an independent force.

Associated festivals: Vasant Panchami, when devotees dress in yellow, offer her flowers, and keep books and instruments before her image for blessing

Worship and significance: Students, artists and seekers of truth invoke her for clarity of mind and eloquence of speech. Unlike deities who grant material boons, Saraswati bestows treasures that cannot be spent — the kind that grow the more they are shared.

Fascinating fact: It’s considered inauspicious to ask Saraswati for wealth, as she is believed to leave when greed enters. In some households, her image is kept in a quiet corner, away from noisy celebration, to honor her preference for peaceful contemplation.

Shiva

The great ascetic, destroyer of illusions, lord of transformation

Domain: Destruction (as renewal), transformation, meditation, time, cosmic balance

Symbolism: Trident (trishula) for the three aspects of existence (creation, preservation, destruction), crescent moon for mastery over time, serpent for fearlessness, river Ganga flowing from his hair for life-giving power, drum (damaru) for the cosmic sound of creation

Appearance: Shiva’s presence is both serene and terrifying — the stillness of a mountain and the force of a storm. His skin is the cool ash-gray of cremation grounds, reminding all that life is temporary and death only a doorway. His hair is long and matted into jata dreads, coiled high upon his head to cradle the Ganga as it flows down from the heavens. A crescent moon glints among his locks, its silver light softening the fire of his third eye.

Around his neck rests a coiled cobra, unmoving, its forked tongue tasting the air — a symbol of Shiva’s mastery over fear and death. His eyes, when open, seem to look through lifetimes; when closed, they turn inward, diving into the infinite void. He wears a tiger skin around his waist, signifying his victory over animal instincts, and rudraksha beads for spiritual focus. In his hand, the trident gleams like lightning, and at his side the damaru beats out the rhythm to which the universe dances.

In his most iconic form, Shiva appears as Nataraja, the Lord of the Dance. With one leg lifted in a graceful arc and the other pressing down on the dwarf of ignorance, Apasmara, Shiva performs the tandava — the cosmic dance of creation, preservation and destruction. In his four arms he has fire, the damaru drum, a gesture of protection, and a hand pointing to his raised foot, offering liberation. Encircled by a halo of flames, Nataraja is a vision of the universe in motion: every heartbeat, every birth and every dissolution bound together in a rhythm that never ceases.

Mount/Vahana: Nandi, the white bull — a symbol of strength, virility and unwavering devotion. Nandi is Shiva’s constant companion, often depicted kneeling in reverence, facing the entrance of Shiva’s temples.

Mythological role: Shiva is one-third of the Hindu Trimurti, alongside Brahma the creator and Vishnu the preserver. His role as destroyer is often misunderstood; he ends cycles so new ones can begin, clearing away stagnation. He’s the patron of ascetics, yogis and those who seek truth beyond illusion.

His stories are as varied as they are powerful: swallowing the deadly poison (halahala) churned from the cosmic ocean to save creation — the act that turned his throat blue and earned him the name Neelkanth; unleashing his third eye to burn desire to ashes; dancing the Tandava, a cosmic performance that both creates and destroys worlds.

Consort and family: Husband of Parvati; father of Ganesha and Kartikeya

Associated festivals: Maha Shivaratri, when devotees fast, chant and keep vigil through the night in his honor.

Worship and significance: Shiva is worshipped in the form of the lingam, a phallic symbol of divine energy and creative potential. Devotees seek his blessing for liberation from worldly attachments and the courage to face transformation.

Fascinating fact: In many villages, Shiva is considered the most approachable of the great gods — Bholenath, the simple lord — quick to grant blessings to anyone who approaches him with sincerity, regardless of status or ritual precision.

Shukra

The teacher of demons, master of resurrection

Domain: Wealth, pleasure, diplomacy, resurrection, the planet Venus

Symbolism: The staff for wisdom, the water pot for life-giving knowledge, Venus for beauty and prosperity

Appearance: Shukra’s presence is calm yet commanding, with skin like polished sandalwood and eyes that gleam with patient intelligence. His white beard and flowing hair mark the wisdom of ages, while his garments shimmer with the soft sheen of silver — the light of Venus caught in fabric. In one hand he holds a danda (staff), in the other a kamandalu (water vessel) said to carry the sacred nectar of life itself.

Mount/Vahana: Often depicted seated on a white horse or in a chariot drawn by eight horses, each representing a different aspect of worldly desire.

Mythological role: Shukra serves as the guru to the asuras (often translated as “demons”), guiding them with cunning strategy and unmatched knowledge of the cosmos. His most prized possession is the Sanjivani Vidya, the secret art of reviving the dead — a gift from Shiva after intense penance. This power has tipped the scales in many battles, forcing the devas (gods) to find new ways to win. Despite his loyalty to the asuras, Shukra is also revered by humans seeking prosperity, charm and the ability to turn rivals into allies.

Consort and family: Married to Jayanti, daughter of Indra; father of Devayani, whose own stories weave through the Mahabharata

Associated festivals: Shukravar (Fridays), dedicated to Venus, are considered auspicious for his worship.

Worship and significance: Followers seek Shukra’s blessing for wealth, harmonious relationships and diplomatic skill — but also for protection against enemies, knowing his allegiance to the asuras makes him an expert in countering adversaries.

Fascinating fact: In astrology, Shukra is linked to artistic talent and sensual pleasures; those under his favor are said to possess irresistible charm and an eye for beauty.

Sita

The steadfast queen, born of the earth and emblem of virtue

Domain: Purity, devotion, courage, self-sacrifice, the ideal of righteous womanhood

Symbolism: Lotus for grace and spiritual beauty, the Earth as her mother, fire as a test of truth, her role as Rama’s equal in love and suffering

Appearance: Sita’s beauty is quiet but unshakable — the kind that deepens the longer you look. Her skin carries the glow of fresh earth after rain, and her eyes, large and steady, hold both tenderness and the weight of trials endured. She wears silks in shades of gold and crimson, with a long veil that frames her face and flows down her back like a stream of sunlight. Jewels gleam lightly at her wrists and neck, never ostentatious, as if she wears them more from tradition than vanity.

In art, she is often shown beside Rama, her posture dignified but never submissive — her head high, her gaze calm. In exile, she appears barefoot among the forest trees, her sari plain, her only ornaments the garlands of flowers she strings with her own hands.

Mount/Vahana: None. Sita’s journeys are always made on foot or by chariot, sharing the same path as her companions. Her lack of a mount reflects her role as an equal partner in hardship rather than a divine figure set apart from mortal trials.

Mythological role: Sita’s life is told in the Ramayana. Found as an infant in a furrow while King Janaka was plowing the fields, she is said to be the daughter of Bhumi Devi, the Earth goddess herself. She grows to marry Rama after he wins her hand by stringing the great bow of Shiva — a feat no other suitor could accomplish.

Her devotion to Rama is absolute: When he’s exiled to the forest for 14 years, she insists on joining him, trading palace comforts for the rigors of wilderness. Her greatest trial comes when she’s abducted by the demon Ravana and held captive in Lanka. Despite months of pressure, she remains unshaken in her loyalty, her only comfort the hope of Rama’s arrival.

After her rescue, she endures the Agni Pariksha, the trial by fire, to prove her purity. In later life, when her character is doubted once more, she chooses to return to the embrace of her mother, the Earth, which parts to receive her — a final act of dignity and self-possession.

Consort and family: Wife of Rama, daughter of King Janaka and Queen Sunaina

Associated festivals: Sita Navami, celebrated especially in Mithila, her birthplace.

Worship and significance: Sita is revered as the ideal of marital devotion, but also as a figure of resilience and moral strength. She embodies the idea that true virtue remains intact, even in the face of injustice.

Fascinating fact: In some folk traditions, Sita is worshipped as an incarnation of Lakshmi, born to accompany Vishnu’s avatar Rama in his earthly mission — making her both queen and goddess.

Vishnu

The preserver and protector of cosmic order

Domain: Preservation, protection of dharma, restoration of balance, compassion

Symbolism: Conch (shankha) for the sound of creation, discus (chakra) for the mind’s sharpness and the destruction of evil, mace (gada) for strength, lotus (padma) for purity rising from the world’s chaos

Appearance: Vishnu’s form is majestic yet serene — the steady, unshakable center of the universe. His skin is the rich blue of the deepest ocean, his eyes calm pools that seem to hold the reflection of the cosmos itself. He’s adorned in golden silk garments and an abundance of jewels — armlets, necklaces, a crown studded with rare gems — yet nothing about him feels over the top. It’s as if the wealth of creation naturally rests upon him.

In his four hands, he holds his eternal emblems: the lotus, delicate and alive; the mace, heavy with power; the discus, spinning and radiant like a miniature sun; and the conch, ready to sound the victory of righteousness. His posture is relaxed but alert, the quiet readiness of a ruler who acts when the time is right.

Mount/Vahana: Garuda, the mighty eagle, with a wingspan that can blot out the sun. Garuda’s golden feathers flash like lightning as he soars, carrying Vishnu effortlessly across the three worlds: the heavens, the Earth and the underworld. He’s both mount and ally, a living embodiment of speed, loyalty and fearlessness.

Mythological role: Vishnu is the preserver of the Hindu Trimurti, standing alongside Brahma the creator and Shiva the destroyer. His duty is to maintain cosmic balance, stepping into the world whenever evil threatens to overwhelm good. To do this, he takes on avatars — earthly incarnations — to set things right. These include Rama, the noble prince; Krishna, the divine lover and strategist; Narasimha, the man-lion who burst from a pillar to save his devotee; and many others.

When not incarnated, Vishnu rests upon the infinite serpent Ananta (Shesha), floating on the cosmic ocean. From his navel grows the lotus that births Brahma, showing that preservation isn’t separate from creation but intertwined with it.

Consort and family: Married to Lakshmi, goddess of wealth and prosperity, who accompanies him in each of his avatars

Associated festivals: Vaikuntha Ekadashi, Janmashtami (for Krishna), Rama Navami (for Rama)

Worship and significance: Vishnu is worshipped across India in many forms, from the grandeur of temple idols to the small household shrines where his avatars are honored. Devotees seek him for protection, moral clarity, and the assurance that no matter how dark the times, the preserver will arrive.

Fascinating fact: Vishnu’s discus, the Sudarshana Chakra, is said to move at the speed of thought and can cut through anything — but it only strikes when guided by righteousness, never in anger or vanity. –Wally