From the fever dream of Pedro Linares to the ultra-popular Oaxacan woodcarvings started by Manuel Jiménez, these fantastical folk art animals are sure to delight.

A winged dog alebrije on the workbench at the family home of Manuel Jiménez, who popularized the small, brightly painted, whimsical woodcarvings known as alebrijes.

I can clearly remember the first time I was introduced to Oaxacan woodcarving. It was the early ’90s and I was working for the Nature Company. We received a shipment of whimsical wooden frogs. I purchased a brightly painted one with an upturned head, saucer-like eyes, a cartoonish grin and exaggerated outstretched limbs more like a cat’s than an amphibians. Little did I know I was on my way to becoming a collector of this art form.

“Pedro Linares fell ill and had a fever dream where strange zoomorphic creatures materialized in a dark forest chanting the word, “Alebrije… alebrije… alebrije.” ”

When Wally and I decided to venture beyond CDMX and visit Oaxaca, Mexico, I knew it’d be a dream come true for us. We are drawn to cultural destinations with vibrant histories — and this one included colorful carvings of arte popular: animals, devils, mythical beasts and skeletons.

Pro tip: I always pack bubble wrap and tape in our suitcase in anticipation of what we will inevitably buy.

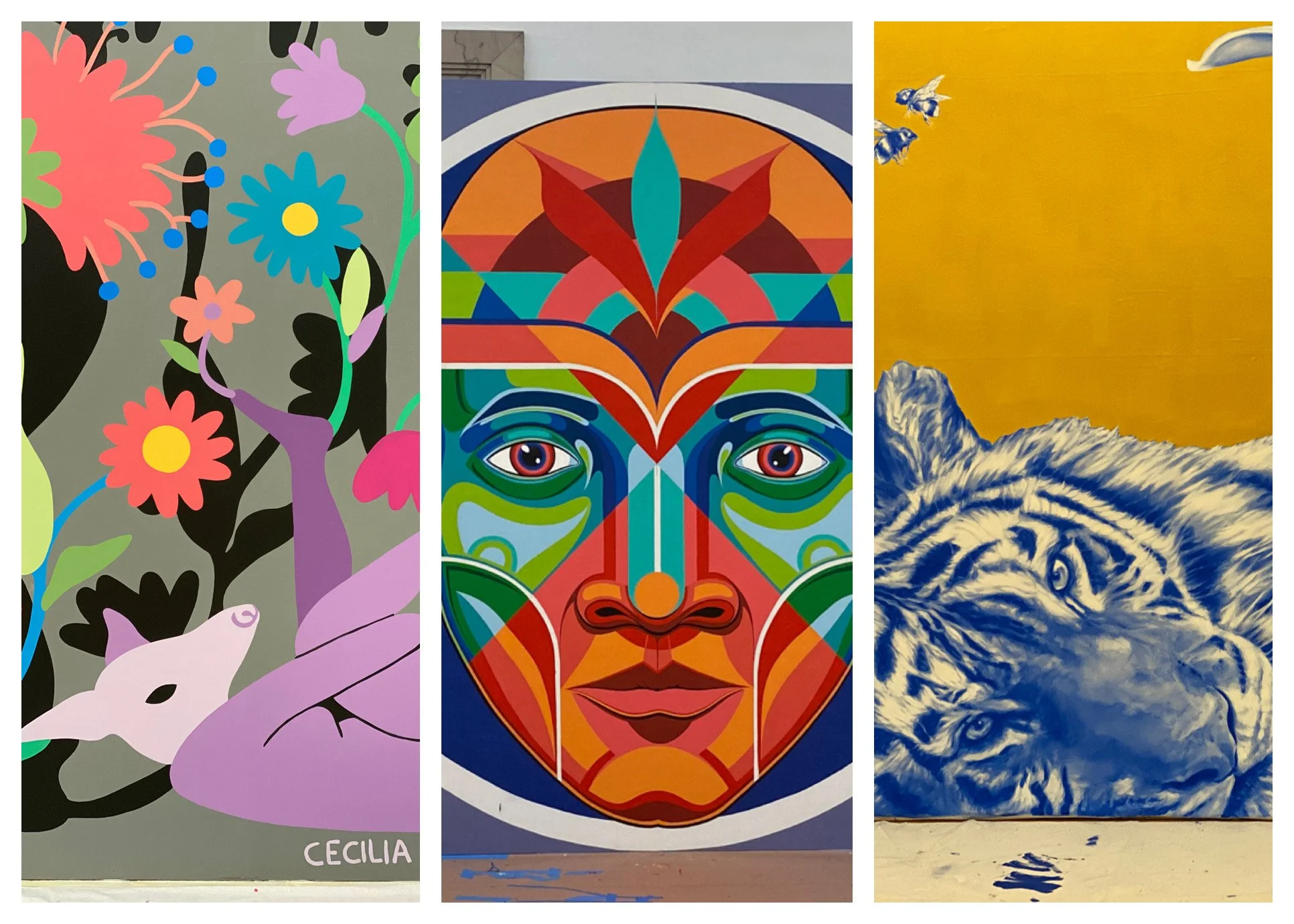

Three alebrijes from Duke and Wally’s collection

Object Lesson: Woodcarving’s Origins in Mexico

To get a sense of history, like many things having to do with Mexico, we must look to the Spanish conquistadors who conquered the Aztec Empire. Indigenous craftspeople shifted, in large part, to creating Catholic objects of saints, angels, crosses and ornate altarpieces for colonial churches. Native Mexicans still made masks for ritual dances and festivals, and Dominican friars used them as visual aids to theatrically act out parables from the Bible as a means to sway the natives to convert to Christianity.

A lion mask from a Mexican woodcarver

Fast-forward to the construction of the Pan-American Highway in the 1940s, which enabled tourists to travel to rural pueblos and led to the increased production of art objects as souvenirs. Although Oaxacan woodcarvings, known as alebrijes (pronounced ah-lay-bree-hays), in their current form have been around for less than 50 years, they have become one of the most popular.

Not all alebrijes are of fantastical beasts — but they do have unexpected colors and patterns.

This art form can be traced back to a single man, Manuel Jiménez, a native of the small village of San Antonio Arrazola. Today the legendary late artist’s compound contains a museum and workshop. His alebrijes are incredible objects that are a cultural jumble of real and imaginary indigenous folklore. It was a natural evolution that other families from Arrazola, as well as those from San Martín Tilcajete and La Unión Tejalapam in particular, applied their ingenuity to create and sell pieces as a source of income.

The first step in creating an alebrije involves a machete like this in the Jiménez family workshop outside of Oaxaca.

Bough Down: How Alebrijes Are Made

These folk art sculptures are considered a young tradition when compared to pre-Hispanic handicrafts such as weaving and pottery. The most popular choice for carving is copal, a softwood that’s easy to work with. Woodcarving involves using non-mechanical tools like machetes, chisels and knives. The exact positioning of the figure is determined by the shape of the piece of wood. Initial cuts are often made with a machete to form a rough idea of what the artist has imagined, while smaller knives and chisels are used to define the final form.

After the object is carved, it’s sanded smooth and left to dry. Those that are carved from a large solid piece of wood can take months to dry. Details like wings, tails and ears are crafted in separate pieces from the main figure, which make them easier to travel with.

Most alebrijes are carved of copal wood. These are drying on a roof at the home and studio of our favorite artisan, Martín Melchor.

The process is a family affair. Generally, it is the men who carve and women who paint. Some are embellished with bold, contrasting acrylic paints and ixtle fiber from the leaves of the maguey plant. They are a source of family pride, and most homes have a small area where finished works are displayed.

It’s believed that alebrijes trace their roots back to the Zapotec tradition of tonas or nahuals, animal spirit guides, which often had human faces, complete with mustaches.

Motifs change, driven by the market’s appetite for novelty and the creativity and imagination of the individual who makes them. Most Oaxacan artisans simply call them figuras, wooden figures. It’s thought that they originally derived from tonas or nahuals, which refer to animal spirit guides from the Zapotec zodiac. But nowadays, these fantastic figures are more often than not referred to as alebrijes.

A cute (?) devilesque papier-mâché alebrije Duke and Wally bought at a store in Chicago

Alebrijes: What’s in a Name?

The first alebrijes as well as the name itself are attributed to Mexico City-born artist Pedro Linares. In 1936 Linares fell ill and had a fever dream where strange zoomorphic creatures materialized in a dark forest chanting the word, “Alebrije… alebrije… alebrije.”

Using his skills as a papier-mâché artist, Linares rendered the creatures from memory, mixing multiple animal body parts, such as the body of a snake, a rooster’s beak, bat wings, lizard legs and a fish’s tail.

Alebrijes began as larger papier-mâché crazy creatures like this one at a mercado in Mexico City.

Jiménez, in turn, was influenced by the highly stylized treatment and colors he saw in the works of Linares — shifting the medium to wood and putting his own mark on the creatures.

The economic growth created by the popularity of these colorful creatures has given many families the opportunity to have a better life in the poorest state in Mexico. Woodcarving has improved the lives of these villagers as evidenced by paved roads, better schools, streetlights and cell phones — none of which existed 20 years ago.

Quality and prices vary widely. Choosing an alebrije is truly a matter of personal taste. It can be overwhelming, so go with your gut. And decide between a colorful chucherría, a small, simple folk object, or a larger labor-intensive fine art gallery-worthy piece.

Many alebrijes now sport multiple intricate patterns.

When you’re in the Oaxaca area and want to visit artisans at their studios, book a tour with the delightful Linda Hanna. And when you see something you like, buy it — because you’ll probably never see anything like it again. Added bonus: The prices at a studio will be much better than at a store or even market. –Duke