The enigmatic allure of the Virgin Mary: From divine purity to unsettling symbolism, we explore the captivating myths and enduring appeal of the original Madonna.

The Virgin Mary takes many guises in art over the centuries, from Queen of Heaven to the Sorrowful Mother whose tears have miraculous properities.

In art, God is often portrayed as an ancient, white-bearded man in flowing robes, a benevolent figure who watches over humanity from on high. Jesus, meanwhile, is typically depicted in various key moments from his life, such as his birth, crucifixion and resurrection. He walks on water and performs other miracles and has his Last Supper.

But the Virgin Mary is a complex and enigmatic figure who wears many guises. Often cloaked in modesty, she’s seen as a symbol of hope, love and sacrifice. She’s portrayed as the ultimate role model for Christian women, the daughter of God, the bride of her own son and a regal queen. Her story is a richly woven tapestry of myths and symbols, each thread imbued with meanings that have been interpreted in countless ways throughout history.

As we delve into the realm of religious art and symbolism, we find her as a fertility goddess known as the Black Madonna, along with a loving mother whose tears and breast milk have magical healing powers. Amid the varied representations through the centuries, one thing remains certain: Mary’s enduring appeal as a divine figure.

Mary, Queen of Heaven by the Master of the Saint Lucy Legend, circa 1495

Maria Regina: Queen of Heaven

Mary, the paragon of purity, couldn’t be left to rot in the grave like a mere mortal. So, the early Church fathers devised a bold solution: They declared that she had been taken up to Heaven in an event known as the Assumption, where she now reigns as a celestial queen.

Popes viewed the Virgin Mary as a powerful propaganda tool. With their ties to the Queen of Heaven, they could legitimize their authority on earth and cemented the strong tie between Mary and Catholicism, centered in Rome: “The more the papacy gained control of the city, the more veneration of the mother of the emperor in heaven, by whose right the Church ruled, increased,” explains Marina Warner in her 1976 book Alone of All Her Sex: The Myth and the Cult of the Virgin Mary.

The Coronation of the Virgin by Diego Velázquez, 1636

John VII was the first pope to have himself painted in prostration at the feet of the Virgin, in the basilica of Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome.

Madonna della Clemenza icon from the church of Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome, 8th century. It’s the first to show a pope, John VII, prostrating himself at her feet (though it’s hard to make out now).

The coronation of Mary was first depicted in the 12th century, from an apse mosaic at Santa Maria to niches of French cathedrals, and became a favorite theme of Christendom. Christ is shown crowning his mother, switching the moment of her triumph from the Incarnation (when she conceived the son of God) to the Assumption (when she was taken up to Heaven).

Coronation of the Virgin by Fra Angelico, 1435

The imagery of a divine queen worked well to legitimize not only popes but royalty and its system of inequality as well. “For by projecting the hierarchy of the world onto heaven, that hierarchy — be it ecclesiastical or lay — appears to be ratified by divinely reflected approval; and the lessons of the Gospel about the poor inheriting the earth are wholly ignored,” Warner writes.

“It would be difficult to concoct a greater perversion of the Sermon on the Mount [Christ’s ethical code, focusing on compassion, selflessness, etc.] than the sovereignty of Mary and its cult, which has been used over the centuries by different princes to stake out their spheres of influence in the temporal realm,” Warner continues, “to fly a flag for their ambitions like any Maoist poster or political broadcast; and equally difficult to imagine a greater distortion of Christ’s idealism than this identification of the rich and powerful with the good.”

The Coronation of the Virgin With Angels and Four Saints by Neri di Bicci, circa 1470

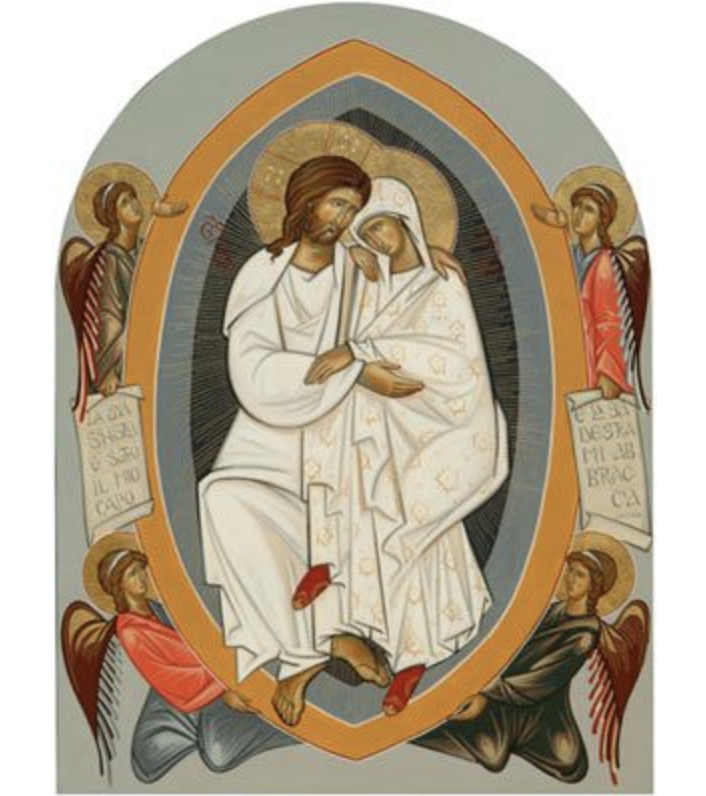

The Bride of Christ: Incest Is Best?

As shocking as it may seem, the Virgin Mary was, for a while, depicted as the bride of her own son, Jesus.

How could this have come about? Warner suggests the influence of Middle Eastern mystery religions, which played up males forming unions with females. The Canaanite god Baal coupled with his sister, Anat. In Syria, the shepherd Tammuz became the lover of the sky goddess Ishtar. The Phrygian cult featured Cybele and Attis, who died castrated under a tree. And Egyptian mythology tells the tale of Osiris, the god of the dead, who was chopped into pieces and put back together by his sister-wife, Isis.

RELATED: A pictorial glossary of the so-called pagan gods of the Old Testament

The nuptials of these divine beings mirrored the joining of earth and sky at the dawn of creation.

You wouldn’t marry your mother, would you — even if she was the Virgin Mary?!

“Thus marriage was the pivotal symbol on which turned the cosmology of most of the religions that pressed on Jewish society, jeopardizing its unique monotheism,” Warner writes. “It is a symptom of their struggle to maintain their distinctiveness that the Jews, while absorbing this pagan symbol, reversed the ranks of the celestial pair to make the bride God’s servant and possession, from whom he ferociously exacts absolute submission.”

From this foundation, Cyprian of Carthage, in the 3rd century, accused virgins who flirted of committing adultery against their true husband, Christ.

And then, of course, there are nuns, whose consecration ceremony includes getting a ring that designates them as a bride of Christ. Talk about polygamy on a mass scale!

But it wasn’t really until 1153, when Bernard of Clairvaux gave multiple sermons on the Old Testament’s Song of Songs — “that most languorous and amorous of poems,” as Warner calls it. In one of these, Bernard preached, speaking of Christ and the Virgin Mary:

But surely will we not deem much happier those kisses which in blessed greeting she receives today from the mouth of him who sits on the right hand of the Father, when she ascends to the throne of glory, singing a nuptial hymn and saying: “Let him kiss me with the kisses of his mouth.”

Pagan influences aside, I’m puzzled as to how this incestuous idea ever caught on among Christians.

The Virgin and Child by Dirk Bouts, circa 1465

Maria Lactans: The Milk-Squirting Mary

While Mary was exempt from Eve’s punishment of bearing children in pain, there was one biological function allowed her: breastfeeding. “From her earliest images onwards, the mother of God has been represented as nursing her child,” Warner says.

The Virgin Mary depicted with squirting breasts?! This is one iconography I’ve got to milk for all its worth.

Where did this idea come from? “The theme of the nursing Virgin, Maria Lactans, probably originated in Egypt, where the goddess Isis had been portrayed suckling the infant Horus for over a thousand years before Christ,” Warner explains.

RELATED: In the New Testament, Mary wasn’t mentioned as being a virgin. Find out why early Christians insisted upon Mary being pure.

Madonna Nursing the Child (Maria Lactans) by Erasmus Quellinus the Younger, circa 1614

Part of this symbolism derives from a mother providing much-needed nourishment: “For milk was a crucial metaphor of the gift of life,” Warner continues. “Without it, a child had little or no chance of survival before the days of baby foods, and its almost miraculous appearance seemed as providential as the conception and birth of the child itself.”

And, not surprisingly, Mary’s milk was miraculous. A favorite medieval tale, including a version in French by Gautier de Coincy, tells how a faithful monk was dying of a putrid mouth filled with ulcers. He reproached the Madonna for neglecting him, and chastened, she appears at his bedside:

With much sweetness and much delight,

From her sweet bosom she drew forth her breast,

That is so sweet, so soft, so beautiful,

And placed it in his mouth,

Gently touched him all about,

And sprinkled him with her sweet milk.

As Warner writes, “Needless to say, the monk was rendered whole again.”

According to a 14th century legend, Saint Bernard prayed before a statue of Mary. It came to life, and the Virgin placed her breast in Bernard’s mouth, nursing him as she did the baby Jesus.

The Madonna’s miracle milk became a nearly ubiquitous relic in Europe. “From the thirteenth century, phials in which her milk was preserved were venerated all over Christendom in shrines that attracted pilgrims by the thousands. Walsingham, Chartres, Genoa, Rome, Venice, Avignon, Padua, Aix-en-Provence, Toulon, Paris, Naples, all possessed the precious and efficacious substance,” Warner says.

John Calvin, the church reformer, had a scathing opinion about these claims. “There is no town so small, nor convent … so mean that it does not display some of the Virgin’s milk,” he wrote in his Treatise on Relics. “There is so much that if the holy Virgin had been a cow, or a wet nurse all her life she would have been hard put to it to yield such a great quantity.”

The idea of a breastfeeding mother of God waned in the Renaissance, when high-born women found it indecent to do the job themselves and outsourced the task to wetnurses. Plus, it was deemed indecorous to depict Mary with her breast exposed with the increasing idea that a woman’s body was shameful. Mary, with the Immaculate Conception, was born without original sin and therefore avoided Eve’s curse — and by the 16th century, that included being exempt from suckling the Christ child.

Madonna in Sorrow by Juan de Juni, 1571

Mater Dolorosa: The Sorrowful Mother

The caregiving image of Mary gave way to a mother mourning her dead son, what’s known as the Mater Dolorosa. The cult began in the 11th century, reaching full fruition in the 14th century in Italy, France, England, the Netherlands and Spain. The culmination of this iconography? Michelangelo’s La Pietà.

La Pietà by Michelangelo, 1499

Again, we have Ancient Egypt, and the surrounding region’s myths, to thank for this representation. The Egyptian goddess Isis sorrowfully wandered the land, collecting the pieces of her dismembered brother-husband, Osiris. When she finds his coffin, she caresses Osiris’ face and weeps.

And she’s not the only weeping woman of the ancient Middle East. Dumuzi, the shepherd and “true son” of Sumerian myth, was sacrificed to the underworld, tortured by demons (much like Christ later, during his Passion and descent into Hell). The goddess Inanna, the Queen of Heaven, weeps for him.

It seems likely that Christians picked up this iconography — spurred on by the horrors of the Black Death, when the bubonic plague swept the continent, wiping out one-fifth of the entire population. “It aroused penitential fever in a way never seen before, and gave the image of the Mater Dolorosa weighty contemporary significance,” Warner points out.

Madonna in Sorrow by Titian, 1554

Once again, Mary’s bodily fluids have healing properties. “The tears she sheds are charged with the magic of her precious, incorruptible, undying body and have the power to give life and make whole,” Warner explains.

This cult has lasted to the present day. Many of us have heard stories of statues of the Virgin that miraculously weep.

“Contemporary prudishness has tabooed the Virgin’s milk, but her tears have still escaped the category of forbidden symbols, and are collected as one of the most efficacious and holy relics of Christendom,” Warner says. “They course down her cheeks as a symbol of the purifying sacrifice of the Cross, which washes sinners of all stain and gives them new life, just as the tears of Inanna over Dumuzi fell on the parched Sumerian soil and quickened it into flower.”

The Virgin of Greater Pain and Transfer of Great Power

RELATED: Learn more shocking things about the Virgin Mary!

The Black Madonna of Monserrat

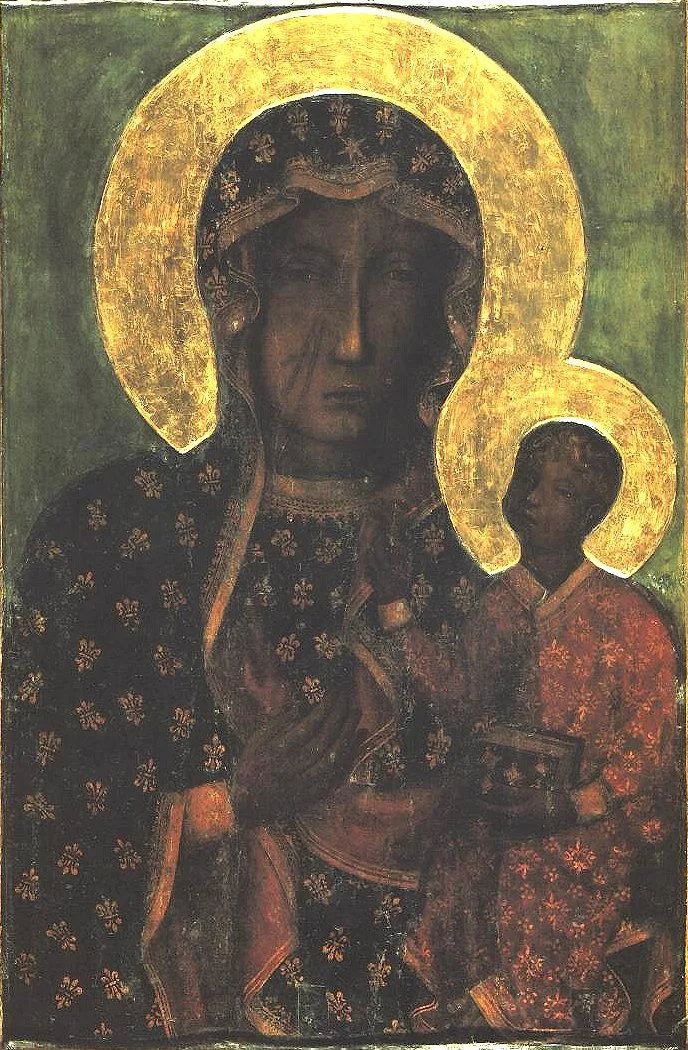

The Black Madonna: Our Lady of Montserrat

Most Western depictions of Mary present her skin as lily-white, untouched by corruption, despite the fact that she is undeniably Middle Eastern. So it’s all the more surprising to see the emergence of the Black Madonna, a dark-skinned version that became popular among the medieval Benedictine monks in Montserrat, Spain.

The monks saw the lushness of their mountain as a mirror of Mary. As such, her icon took on aspects of a fertility goddess.

But in a bizarre twist (or perhaps not, given that Mary was a Jew from Judea), the Virgin had dark skin, which led to her being known as the Black Madonna. In fact, she’s known locally as La Moreneta, the Little Dark One. The depiction spread to other places of worship, among them Chartres, Orléans, Rome and Poland.

The Black Madonna of Częstochowa, Poland

“The Church often explains their blackness in allegorical terms from the Song of Songs: ‘I am black, but comely, O ye daughters of Jerusalem’ (Song of Solomon 1:5),” Warner writes. “[B]ut another theory about their color is even more prosaic: that the smoke of votive candles for centuries has blackened the wood or the pigment, and when artists restored the images, they repainted the robes and jewels that clothe the Madonna and Child but out of awe left their faces black.”

The shrine at Montserrat is one of the longest continuous cults of Mary, especially popular with newly married couples. Here she has dominion over marriage, sex, pregnancy and childbirth — odd for a virgin but not for a fertility goddess.

The Black Madonna at St. Mary’s Church in Gdansk, Poland

A gruesome legend illustrates Mary’s power. A woman gives birth to a lump of dead flesh. But when she prays to Our Lady of Montserrat, it begins to move and is transformed into a beautiful baby boy.

Madonna della Misericordia by Benedetto Bonfigli, circa 1470

Madonna della Misericordia: Our Lady of Mercy

In a merging of her roles as mother and queen, a new depiction of Mary emerged in Umbria, Italy at the end of the 13th century. The Virgin was given a massive cloak which she wrapped over the poor souls gathered at her feet. Towering over them and offering protection, this was the Madonna della Misericordia, Our Lady of Mercy.

Madonna of Mercy by Sano di Pietro, circa 1440s

After the desolation of the Black Death in the late 1340s, this iconography of Mary became the most popular. Monks and laypeople alike would pray to this aspect of the Virgin, asking her to keep them safe from harm.

The Virgin of the Caves by Francisco de Zurbarán, circa 1655

This Mary is often preternaturally large — and her son, Christ, isn’t anywhere to be found, “suggesting that her mercy, directly given, could save sinners,” Warner writes. But that cuts God and Jesus out of the equation and makes the Virgin a goddess in her own right.

So while Our Lady of Mercy spread throughout Europe in the 14th and 15th centuries, it was officially declared heterodox (not in accordance with the accepted Catholic doctrine) and banned by the Council of Trent in the mid-1500s.

Dormition of the Virgin fresco by Frangos Katelanos, 1548

Divine Dominion Over Death

The Virgin Mary has worn many guises over the years, from a gentle breastfeeding mother to imperial queen to tutelary goddess.

“If travelers from another planet were to enter churches, as far flung as the National Shrine of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C., or the Catholic cathedral in Saigon, or the rococo phantasmagoria of New World churches, and see the Virgin’s image on the altar, it would be exceedingly difficult for them to understand that she was only an intercessor and not a divinity in her own right,” Warner points out.

There are surely many factors that have led to Mary’s enduring appeal, starting with her co-opting of ancient mythology like the Egyptian goddess Isis. Many cultures find it fitting to worship the female spirit — something glaringly missing in the often-misogynistic views of Christianity.

Detail from Assumption of Mary by Peter Paul Rubens, circa 1617

But Warner has a theory: “For although the Virgin is a healer, a midwife, a peacemaker, the protectress of virgins, and the patroness of monks and nuns in this world; although her polymorphous myth has myriad uses and functions for the living, it is the jurisdiction over her death accorded her in popular belief that gives her such widespread supremacy.”

She could be on to something. Think of the final words of the Hail Mary, the best-loved prayer in Catholicism: “Holy Mary, Mother of God, pray for us sinners now and at the hour of our death.” –Wally