Other ways to make white pigment paled in comparison — but was it worth the risk of lead poisoning?

Queen Elizabeth I loved her white makeup (made from a toxic blend of lead and vinegar) so much that she supposedly had an inch’s worth on her face when she died.

White: the color that evokes the purity of freshly fallen snow and the innocence of virgins. If you’ve ever flicked through a bridal magazine, you can’t help but notice the color white — though you no longer need be chaste to wear it.

But how can one of the earliest and most important pigments produced by mankind be one of the deadliest in the history of color? Its popularity was all the more alarming, given that it could result in lead poisoning (also referred to as painters’ colic or plumbism). Adult symptoms include headaches, abdominal cramps, joint and muscle pain and high blood pressure. Children can suffer developmental delays, learning difficulties and weight loss.

“Geishas used lead white makeup — it contrasted beautifully with their teeth, which they painted black.”

Japanese geishas are part of a long line of standards of beauty that decree that the whiter the skin the lovelier.

A Recipe for Lead White: Don’t Try This at Home

Since antiquity, artists have used pigments to represent the colors they saw in the natural world. Lead was used as the principal white pigment in paintings and glazes from ancient times until the 20th century.

The statues you see in museums and at historic sites were originally painted — and that often included the poisonous lead white.

The laborious process was documented by Roman author and naturalist Pliny the Elder. First, pour a bit of vinegar into the bottom of an earthenware pot. Place a wooden spacer in the pot with a coiled band of lead on top so that only the rising vapors from the vinegar come in contact with the metal. The clay vessel was then surrounded by fresh animal dung and left in a sealed chamber for 30 days. As the manure fermented, it released carbon dioxide, which reacted with the vinegar and chemically corroded the lead, producing the perfect conditions for white papery flakes to grow.

Pliny the Elder shared his recipe for the bright but toxic shade of white made from lead.

After a month or so, some poor soul was sent to retrieve the pieces of lead, which were now covered with a crust of lead carbonate. This was scraped, cleaned and washed to remove impurities. The raw pigment was ground into powder, formed into small cakes and left to dry in the sun for several days before being sold.

Sure, the process to make lead white cakes could lead to severe ailments — but it was just so bright and pretty!

The resulting pigment was highly valued by artists. Affordable and dense, painters swore by its ease to work with and primed their canvases with it to make their works appear more luminous.

Art historians are also grateful for its use. When combined with the use of x-ray imaging technology, the paint reveals details such as the earlier stages, alterations and additions of a painting.

A self-portrait of James McNeill Whistler, who used lead white paint in his works.

Whistler: What a Mama's Boy

One such painter who used lead white was the American-born, British-based artist James McNeill Whistler (1834-1903). Whistler is perhaps best remembered for the iconic portrait, painted in 1871, of his mother. Titled Arrangement in Grey and Black, No. 1, most know it as Whistler’s Mother. It was the first artwork by an American artist to be purchased by the French government for display in a museum. When it’s not traveling, it resides at the Musée d'Orsay in Paris. The painting represents the peak of Whistler’s radical method of modulating tones of a single color.

This technique began years earlier when he submitted The White Girl to the 1862 Royal Academy of Arts exhibition in London to demonstrate his talents to the world. The ethereal painting depicts his mistress, Joanna Hiffernan, a well-known beauty who modeled for other artists of the day. Tousled locks of red hair frame her expressionless face as she stands atop a wolfskin rug that, to me, disturbingly resembles the pelt of a yellow Lab.

Whistler’s The White Girl was deemed too modern for the Salon exhibition in Paris.

As far as the British were concerned, the work was too avant-garde. It was rejected by the Academy and ended up in the Salon des Refusés, a protest exhibition organized by the French painter Gustave Courbet.

Whistler later retitled the work Symphony in White, No.1, perhaps after empathetic art critic Paul Manz commented on the subtle variations of white in the Gazette des Beaux-Arts as a “symphonie du blanc.”

Geishas still wear a stark white makeup as a sort of mask.

The Lingering Perception That Pale Is Beautiful

In addition to painting, lead white was used in cosmetics. The controversial quest for lighter skin and its association with beauty, social status and wealth has existed since Ancient Egypt. Women of Ancient Greece and Rome whitened their skin with powders and creams made from lead. Japanese geishas also used it — it contrasted beautifully with their teeth, which they had fashionably painted black using a solution of powdered oak galls and vinegar.

Japanese felt that a geisha’s stark white skin paired perfectly with blackened teeth.

The beauty product Snail White (made from actual snail secretions!) is said to leave your skin more pale — and therefore more beautiful.

When Wally and I visited Thailand, we saw shelves at the 7-Elevens stocked with pink and white boxes of Snail White skincare products to give you paler skin. The main ingredient? Mucus secreted by snails. Pretty!

Queen Elizabeth I first began using her lead white makeup as a sort of putty to spackle smallpox scarring.

Fit For a Queen: From Elizabeth I to Laird’s Bloom of Youth

What could have possessed 15th century European courtiers to smear the stuff on their faces? Queen Elizabeth I (1533-1603) was 29 years old when she was diagnosed with smallpox. She survived the deadly illness but was left with smallpox-scarred skin. She appreciated the cosmetic’s ability to conceal her scars, so she adopted her now-famous chalk-white visage. The queen used Venetian ceruse (also known as spirits of Saturn), a foundation produced by combining powdered lead and vinegar. While it may have smoothed her complexion, it was exceedingly toxic — especially when worn for long periods of time.

Elizabeth I’s legendary white makeup was used to help rebrand herself the Virgin Queen.

Elizabeth used her image to frame the narrative of a virgin queen who didn’t need a husband — she was wedded to her country. When she died at the age of 69, it was rumored that she had a full inch of makeup on her face, which, ironically, may have contributed to her death.

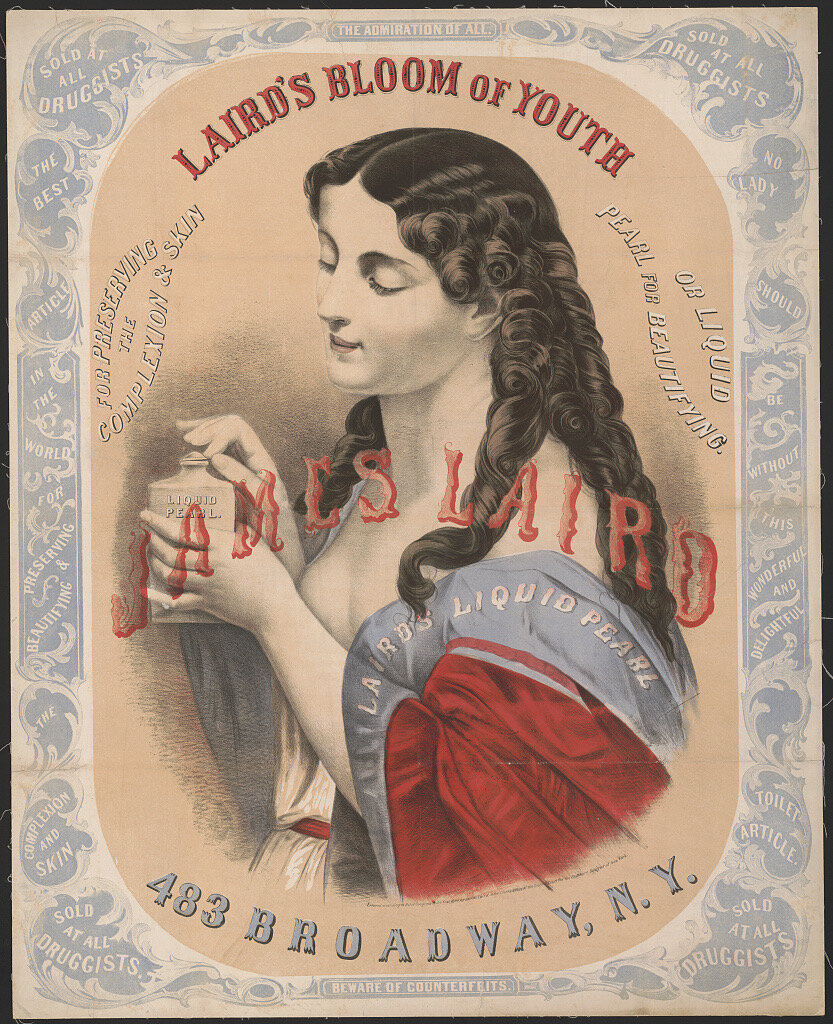

Commercial lead makeup products like George W. Laird’s Bloom of Youth were introduced in the 19th century. Laird ran a series of advertisements in fashionable New York magazines, promising to smooth and whiten the skin.

“It will immediately obliterate all such imperfections, and is entirely harmless. It has been chemically analyzed by the Board of Health of New York City and pronounced entirely free from any material injurious to the health or skin,” the ad (untruthfully) claimed.

Laird’s Bloom of Youth claimed to be harmless — but it wasn’t!

Women took notice and applied Laird’s Bloom of Youth foundation to their faces. Perhaps some women thought that a little bit wouldn’t hurt, and by the time the truth was clear, it was probably too late. –Duke