The stories behind the UK’s magical new stamps are sure to enchant you: the Loch Ness Monster, Beowulf and Grendel, Cornish piskies, selkies and more.

Eight stamps. Eight legends. A whole world of magic compressed into miniature artwork — and honestly? I’ve never wanted to send more mail in my life.

Each one of these beautifully illustrated postage stamps from the Royal Mail is a tiny portal into the legends that have haunted the British Isles for centuries. They’re wild and eerie. I was hooked.

This 2025 Myths and Legends series was brought to life by British illustrator Adam Simpson, whose crisp, almost woodcut-like style lends a timeless gravitas to everything he touches. He’s known for art that feels like it could adorn a high-end gallery wall — or illustrate a children’s book.

It’s perfect for a set of stamps that spans the heroic, the heartbreaking and the downright horrid. The collection draws from English, Scottish, Welsh and Irish folklore, and features not just the obvious icons (yes, Nessie makes an appearance) but some deeper, darker cuts too. Why hello, Grindylow.

Each stamp is a love letter to the past, a celebration of story, and a reminder that folklore isn’t dead — it’s just waiting for the right delivery system. Consider this your guided tour through the tales behind the stamps, complete with monsters, magic, betrayal … and brine.

Beowulf and Grendel

Hero vs. horror in the original monster story

Long before superheroes wore capes, they wore chainmail and boasted a mead hall’s worth of swagger. Beowulf is the OG epic hero — the kind of guy who crosses the sea just to fight your monsters for you. His most famous foe? A grotesque creature named Grendel, who spent his nights tearing warriors limb from limb at the hall of Heorot. The king, Hrothgar, was helpless. Enter Beowulf.

This story comes from the Old English poem Beowulf, thought to have been composed between the 8th and 11th centuries, set in Scandinavia but recorded in a single surviving manuscript from Anglo-Saxon England (now safely stored at the British Library). It’s the oldest known epic in English literature — and it doesn’t pull punches. Beowulf doesn’t just defeat Grendel; he rips his arm clean off and hangs it like a trophy. Brutal. Poetic. Metal.

Grendel himself is one of literature’s great monsters — described as a descendant of Cain, shunned by God, and tormented by the joy he hears in Hrothgar’s hall. He’s more than beast; he’s a symbol of alienation and rage, a product of exile and pain. Some later interpretations even paint him as a tragic figure. Not that Beowulf cared.

Simpson’s stamp captures the legendary fight with clean lines and mythic energy: Beowulf, shirtless and unstoppable, wrestles the twisted figure of Grendel in a composition that feels part medieval tapestry, part comic book panel. It’s dynamic, dramatic — and faithful to the grit of the tale.

This is the legend that launched a thousand English Lit classes, inspired everything from The Lord of the Rings to The Witcher, and proved that even a millennium ago, people loved a good monster fight.

Blodeuwedd

The flower bride who became an owl

Once upon a time in the mythic heart of Wales, a woman was conjured — not born, but created. The magicians Math and Gwydion, meddling in mortal matters as wizards do, wove her from the blossoms of oak, broom and meadowsweet. Her name was Blodeuwedd, meaning Flower Face, and she was made for one purpose: to be the wife of a man cursed never to marry a woman of earthly origin.

You can probably guess how well that turned out.

This tale comes from the Mabinogion, a collection of Welsh medieval stories first written down in the 12th and 13th centuries but based on oral traditions that are far older. It’s one of the most bewitching episodes in the Fourth Branch, a saga steeped in magic, betrayal and transformation.

Though crafted to be the perfect bride, Blodeuwedd had her own ideas. She fell in love with another man, Gronw Pebr, and together they plotted to kill her husband, Lleu Llaw Gyffes. The murder attempt failed, and the consequences were swift and strange (this is myth, after all): Gronw was killed with a spear through a standing stone, and Blodeuwedd was transformed into an owl — a creature of the night, cursed to never show her face in daylight again.

Her story is tragic and richly symbolic. Depending on your lens, Blodeuwedd is either a femme fatale born of male hubris or a wild spirit trapped by expectation who seized a sliver of freedom in the worst way. Either way, she’s unforgettable.

Simpson’s stamp channels the tale’s eerie beauty with a stylized woman caught mid-transformation — petals swirling into feathers as she takes her owl form. It’s the kind of image that lingers, much like the legend itself.

The Loch Ness Monster (Nessie)

The queen of cryptids surfaces again

You can’t talk about UK folklore without invoking Nessie, the shadowy shape that launched a thousand blurry photos and conspiracy theories. She’s the most famous resident of Loch Ness, a deep, cold freshwater lake tucked into the Scottish Highlands — and she’s been allegedly living there since at least the 6th century.

The earliest written mention comes from The Life of St. Columba, penned in the 7th century by Adomnán. According to the account, the saint encountered a “water beast” in the River Ness and performed a miracle to save a man from its jaws. And just like that, Nessie swam her way into the margins of history.

But her modern fame really took off in the 1930s, after a couple driving near the loch claimed to see a massive creature cross the road and slip into the water. Headlines dubbed it a “monster,” and the tabloids never looked back. Since then, Nessie’s been spotted, debunked, photographed, hoaxedand even hunted with sonar. (Spoiler: She remains elusive.)

While scientists say the sightings are likely otters, logs or wishful thinking, the legend endures. Nessie is more than just a maybe-dinosaur. She’s a symbol of mystery, of nature keeping secrets, of something just out of reach. And let’s face it: Everyone wants her to be real.

Simpson’s stamp doesn’t try to pin her down. Instead, it leans into the enigma: Nessie arches out of stylized waters, distant and dreamlike, framed by curling waves and Highland mist. There’s no need to explain her. She just is.

She’s proof that sometimes, the most powerful legends are the ones we can’t quite catch.

Cornish Piskies

Mischief, mayhem and magic in miniature

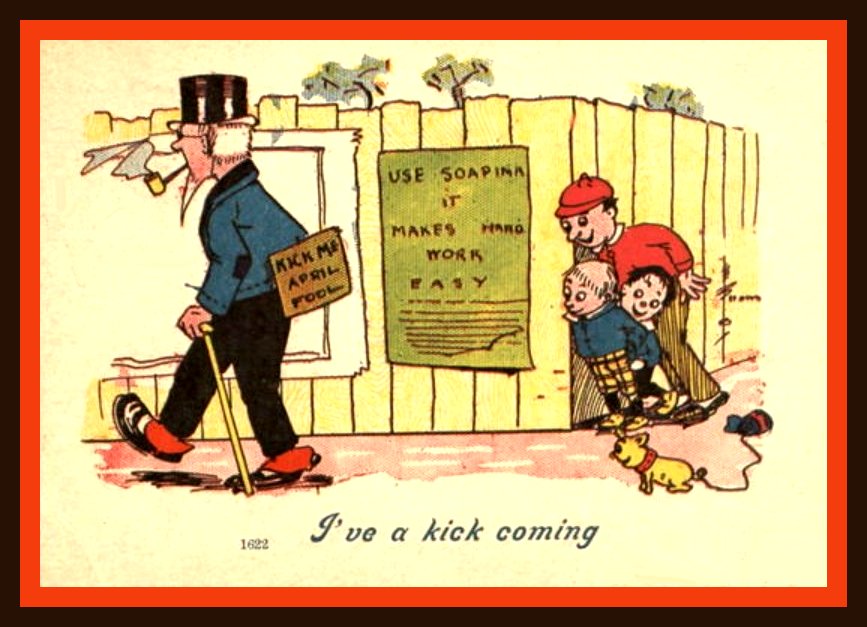

If you ever find yourself turned around on a familiar path in the southwest of England, don’t blame your GPS — blame the piskies. These pint-sized pranksters from Cornish folklore are legendary for leading travelers astray, stealing shiny things, and generally causing low-level chaos with high-level charm.

Piskies (sometimes spelled pixies) have been part of Cornish oral tradition for centuries, possibly even tied to pre-Christian beliefs in nature spirits or ancestral ghosts. They’re native to the moors, tors and coastal cliffs of Cornwall, often dressed in ragged green and red, with pointy ears and a love of laughter at your expense.

But unlike fairies who might hex you or goblins who’ll rob you blind, piskies are mostly harmless. Annoying? Yes. Dangerous? Rarely. They’ve been known to braid horses’ manes, move your keys, and lure people into marshes with giggles and flickering lights. The only remedy if you’ve been “piskie-led”? Turn your coat inside out. That supposedly confuses them. (And maybe earns you their grudging respect.)

In Victorian times, Cornish tourism latched onto piskies as whimsical local mascots—think of them as the original chaotic neutral brand ambassadors. But in older tellings, they’re wild, weird, and deeply tied to the landscape.

Adam Simpson’s stamp captures that dual nature perfectly. The piskies glide through a moonlit glade, wide-eyed and impish, flanked by twisted trees and carrying the evidence of their mischief-making: a lost key, a frayed rope. There’s joy here, but also a touch of the uncanny.

In a world that often takes itself far too seriously, the piskies remind us that a little chaos can be good for the soul.

Fionn mac Cumhaill

The Irish giant whose legend spans countries

Fionn mac Cumhaill (pronounced roughly like “Finn mac Cool”) is Ireland’s answer to Hercules, with a bit of that trickster Hermes thrown in. A warrior, leader, poet and occasional giant, depending on who’s telling it, Fionn is the towering figure at the heart of the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology, a body of tales passed down orally for centuries before being written in Middle Irish texts around the 12th century.

He’s best known as the leader of the Fianna, a band of noble warrior-hunters who roamed Ireland getting into gloriously poetic trouble. But the story that often gets the spotlight — especially on tourist brochures — is the one where Fionn creates the Giant’s Causeway, that eerie, hexagonal rock formation on the northern coast of Ireland. According to legend, Fionn built it as a bridge to Scotland so he could fight a rival giant, Benandonner.

The punchline? When he saw how massive Benandonner really was, Fionn panicked. His wife, Oonagh, disguised him as a baby in a cradle. When Benandonner saw the size of the baby, he assumed the father must be terrifying and fled back to Scotland, tearing up the bridge behind him. A rare myth where wit — and a good partner — win the day.

Fionn also gained prophetic wisdom by burning his thumb on the Salmon of Knowledge, which, yes, is exactly what it sounds like. From that day on, sucking his thumb gave him bursts of insight — a sort of mythic precursor to Google, if Google required seafood and pain.

Simpson’s stamp goes bold: Fionn stands enormous against the rising Causeway, cloak billowing, face stoic. The stones stretch beneath him in their perfect geometric strangeness. It’s both heroic and humorous — a nod to how Irish mythology never shies away from mixing the mighty with the mischievous.

Fionn mac Cumhaill is the kind of figure who straddles legend and landscape — literally — and he still looms large today.

Black Shuck

The devil’s dog that stalks the coast

If you ever find yourself walking alone through the misty lanes of East Anglia — especially near a windswept churchyard — and feel the prickle of something behind you… it might be Black Shuck. Described as a massive, ghostly black dog with glowing red (or sometimes green) eyes, Shuck is one of the U.K.’s most enduring pieces of spectral folklore. He’s part omen, part legend, and all menace.

The name “Shuck” is believed to come from the Old English scucca, meaning “demon” or “fiend.” Reports of this supernatural hound go back centuries, but his most infamous appearance took place on August 4, 1577, during a thunderstorm that ripped through the churches of Bungay and Blythburgh in Suffolk. According to terrified witnesses, the beast burst into the churches during the storm, killing or injuring several people before vanishing in a flash of fire. To this day, scorch marks on the church doors in Blythburgh are said to be Shuck’s claw marks.

But like many creatures of folklore, Shuck’s meaning has shifted over time. In some tales, he’s a harbinger of death, like the Grim Reaper with paws. In others, he’s a protective spirit, quietly walking beside lone travelers to keep them safe.

Simpson’s stamp leans into the fearsome version: a shaggy, howling beast with glowing eyes, set against a backdrop of a castle in a thunderstorm. It’s the kind of image that makes you instinctively glance over your shoulder.

Whether he’s a ghost, a guardian or something in between, Black Shuck reminds us that the line between safety and terror can be as thin as a shadow in the mist.

Grindylow

The creature in the water who waits for misbehaving children

The Grindylow isn’t interested in riddles or redemption. This creature — slimy, long-fingered and lurking just beneath the surface — is the reason your grandmother told you not to go too close to the pond. Native to the folklore of Yorkshire and Lancashire, the Grindylow is a water-dwelling bogeyman whose sole hobby appears to be grabbing children by the ankle and dragging them to a watery doom.

Pleasant, right?

The tale likely began as a cautionary myth, passed through generations in England’s misty north as a way to keep kids away from dangerous pools, marshes and millponds. But the Grindylow isn’t just a PSA in monster form; it’s a creature of genuine nightmare fuel. Often described as having green skin, long, spindly arms and razor teeth, the Grindylow hides in shallow waters, waiting for a ripple, a footstep or a foolish dare.

While it rarely ventures beyond regional lore, the Grindylow got a boost in popular imagination thanks to fantasy literature and modern media — most notably showing up as a minor monster in Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire, where it menaces underwater champions during the Triwizard Tournament. But the original version? Far less CGI-friendly, and far more chilling.

Simpson’s stamp leans into the fearsome. You see the Grindylow emerging from the water — alarmingly sharp claws and teeth just waiting to tear into its next victim. There’s no question what will happen next if you take one more step closer to the edge.

More obscure than Nessie and more vicious than the piskies, the Grindylow doesn’t want your attention. It wants your ankles.

Selkie

The seal who loved and left

The selkie’s story is one of yearning: for freedom, for the sea and for a life that can never fully belong to land. These shape-shifting beings come from Orkney and Shetland folklore, where the wind howls and the sea sings. Selkies are seals in the water — but when they come ashore, they shed their sleek skins and become beautiful humans, often just long enough to fall in love, or be taken.

And that’s where the heartbreak begins.

The most common version of the tale? A fisherman (or crofter, or lonely islander) spies a selkie woman dancing on the shore in her human form. He steals her seal skin so she can’t return to the sea, and convinces her — sometimes gently, sometimes not — to become his wife. They live together, raise children, and for a time, there’s a strange sort of peace. But the selkie always gazes longingly at the waves. And when she finds her hidden seal skin at last, she returns to the ocean without a backward glance.

Other versions flip the roles — selkie men seduce mortal women, especially those with “the yearning,” and disappear when the tide calls. Regardless of who leaves, the ending is rarely happy. Selkie stories are salt-soaked with longing, freedom and loss. They’re metaphors for desire, captivity and returning to one’s true self — even if it hurts.

These tales date back centuries, passed down orally in Scotland’s far northern islands and coastal fishing communities. And while they’ve inspired everything from poetry to films (The Secret of Roan Inish and Song of the Sea, for instance), the root myth remains as fluid and mysterious as the tide itself.

Simpson’s stamp is pure melancholy magic: a selkie woman caught mid-transformation, cloak of seal skin slipping from her shoulders, hair trailing like seaweed. The horizon behind her is misted, the waves beckoning. You can almost hear them whispering her name.

The selkie doesn’t roar or bite. She simply leaves — and that’s what makes her legend linger.

Stamped, Sealed, Enchanted

The Royal Mail’s Myths and Legends series doesn’t just celebrate folklore; it resurrects it. These aren’t dusty old tales tucked away in textbooks — they’re living, breathing stories full of monsters, mischief, heartbreak and heroism. And thanks to artist Adam Simpson’s stunning illustrations, they feel both timeless and vividly alive.

From the brute strength of Beowulf to the quiet sorrow of the selkie, each stamp invites you to pause and dive deeper. To trace the origins. To hear the whispers of ancient moors, haunted coastlines and flower-strewn spells. They remind us that storytelling is a kind of magic.

So yes, I’ll be collecting these. But more importantly, I’ll be sharing them — because folklore, like a good letter, was meant to be passed on. –Wally