One of the Gnostic gospels, this “heretical” text paints a controversial picture of Christianity and the apostle who is said to have betrayed Jesus.

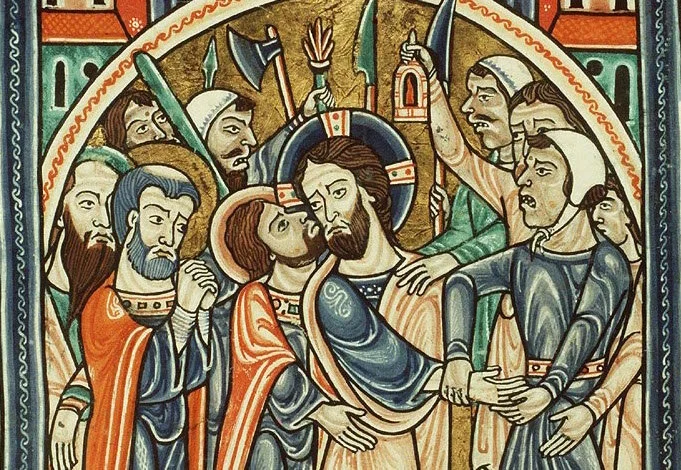

The Betrayal of Jesus by Giotto di Bondone, 1304. But what if Judas turning Jesus over to the authorities was all part of the plan?

Most people believe that Christianity has always been fully formed, as if the New Testament was handed down from God Himself.

But that’s not the case. We can be forgiven for falling under the impression “that Christianity actually was a single, static, universal system of beliefs,” write Elaine Pagels and Karen L. King in Reading Judas: The Gospel of Judas and the Shaping of Christianity. “Creating this impression was itself a remarkable achievement — one to which certain ‘fathers of the church’ were dedicated. But they did so precisely because they realized how diverse Christian groups were, and they feared that controversies over basic issues—like those revealed in the Gospel of Judas — might undermine the ‘universal church’ they were trying to build, along with the authority they were claiming for their church alone.”

But the discovery of additional texts like the Gnostic Gospels shows there were dissenting views and that early Christianity was anything but uniform. Church founders very carefully debated which gospels to keep — and which to discard.

The sorry state of the first page of the Gospel of Judas. That’s what a humid safety box and a stint in a freezer will do to ancient papyrus!

Unearthing the Gospel of Judas

The Gospel of Judas was written by an unknown author in Greek around 150 CE. Deemed heretical, the only known surviving copy is one that was translated into Coptic in the 4th century and discovered in the 1970s in Middle Egypt. It was part of what’s called the Tchacos Codex, which had a rough go of it, from its burial cave to a humid safety deposit box — even being frozen at one point!

A church father named Irenaeus rails against this particular group of Christians in work, Against Heresies, written around 180 CE:

They declare that Judas the traitor … alone, knowing the truth as no others did, accomplished the mystery of the betrayal; by him all things, both earthly and heavenly, were thus thrown into confusion. They produced a fictitious history of this kind, which they style the Gospel of Judas.

An early Christian leader, Irenaeus, railed against what he deemed heresies, including the Gospel of Judas.

This was at a time when Christianity had developed into numerous offshoots, with quite different beliefs. The Roman Emperor Constantine, a surprising but passionate convert to Christianity, attempted to resolve the differences by supporting the bishops he gathered together in 325 CE at the Council of Nicaea in present-day Turkey. These early church fathers went through the existing literature and chose what was canon and what was heresy.

“The traditional history of Christianity is written almost solely from the viewpoint of the side that won, which was remarkably successful in silencing or distorting other voices, destroying their writings, and suppressing any who disagreed with them as dangerous and obstinate ‘heretics,’” Pagels and King write.

Those who dared to continue practicing beliefs the bishops had forbidden found their buildings confiscated or burned to the ground over the following centuries.

the shocking claims of the Gospel of Judas

The Gospel of Judas is a quick but confounding read. (At one point, for example, the writer offers this aside, which suggests that the son of God had the power to shapeshift: “Frequently, however, he would not reveal himself to his disciples, but you would find him in their midst as a child.” Judas 1:8).

Marvin Meyer and F. Gaudard translated the text into English for the National Geographic Society in 2006, and it wasn’t an easy task. As stated, the poor manuscript had been through the ringer. Improper handling and storage — including that stint in a freezer — had reduced the papyrus to fragments.

Here are four shocking claims made in the Gospel of Judas that completely disrupt what we know of Christianity.

The Taking of Christ by Caravaggio, circa 1602. The Christianity we know today was shaped by Church leaders 300 years after Jesus’ death — and early followers didn’t agree on doctrines.

1. Judas wasn’t a villain — he was actually Jesus’ favorite disciple and was asked by Christ to betray him.

This is the statement that’s the most shocking, even to this day, entirely turning the Gospels of the New Testament on their head.

“For thousands of years, Christians have pictured Judas as the incarnation of evil. Motivated by greed and inspired by Satan, he is the betrayer whom Dante placed in the third lowest circle of hell,” Pagels and King write. “But the Gospel of Judas shows Judas instead as Jesus’s closest and most trusted confidant — the one to whom Jesus reveals his deepest mysteries and whom he trusts to initiate the passion.”

On some level, this shouldn’t be such a big surprise. In all of the New Testament gospels, Jesus anticipated and even embraced his own death. So it’s not too far a stretch to imagine he worked with Judas to put his plan in motion.

2. The other apostles actually worship a false God and are mistaken in their beliefs about the Eucharist and martyrdom.

The Gospel of Judas begins with Jesus laughing at the apostles (he laughs mockingly throughout the work) as they celebrate the Eucharist, believing that they were eating the body of Christ and drinking his blood — a practice that always struck me as eerily cannibalistic.

Matthew 26:26-28 reads, “As they were eating, Jesus took some bread and blessed it. Then he broke it in pieces and gave it to the disciples, saying, ‘Take this and eat it, for this is my body.’

The Gospel of Judas declares that the apostles got the Eucharist all wrong.

“Jesus’s laughter is a kind of ridicule or mockery intended to shock the disciples out of their complacency and false pride,” Pagels and King write. “Their deepest problem is that they don’t know they have a problem; they wrongly think they are already righteous, with their prayers and practices of piety.”

Despite the hopeful message of salvation in the gospel, there’s a cryptic declaration near the beginning: Jesus said to them, “Do you (really think you) know me — how? Truly I say to you, no race from the people among you will ever know me.” Judas 2:10-11.

The apostles then have a dream that horrifies them: Priests sacrificed their children and wives. Some had sex with other men, while some engaged in slaughter, amongst an array of other “sins and injustices.”

Jesus once again laughs (I told you) and informs them that they are the ones doing those deeds and that they worship a false God.

This is, in part, supposed to be a commentary on the craze of martyrdom. Not surprisingly, many followers of Jesus at the time weren’t happy with the trend that persecuted Christians should eagerly embrace torture and violent death.

“Their anger was directed less against the Romans than at their own leaders for encouraging Christians to accept martyrdom as God’s will, as though God desired these tortured bodies for his own glory,” Pagels and King write.

The apostles just didn’t understand Jesus’ teachings, according to the Gospel of Judas — even the “God” they worshipped was false!

The author of the Gospel of Judas points out what he feels is a stunning contradiction: “while Christians refuse to practice sacrifice, many of them bring sacrifice right back into the center of Christian worship — by claiming that Jesus’s death is a sacrifice for human sin, and then by insisting that Christians who die as martyrs are sacrifices pleasing to God,” the authors point out.

Jesus tells the disciples that the supposed “God” they worship is actually a lower angel who’s leading them astray. (This is where the gospel starts going a bit off the rails and gets all metaphysical.)

St. Stephen, said to be the first Christian martyr, as painted by Rembrandt.

3. Judas didn’t commit suicide — he was, in fact, the first Christian martyr.

The Gospel of Matthew states that Judas, ashamed at his betrayal, returned the 30 pieces of silver that had been his bribe, and hanged himself.

The Suicide of Judas by John Canavesio, circa 1492 — but did Judas really hang himself? The Gospel of Judas has him meeting a different gruesome end.

But the Gospel of Judas tells a different tale: The other disciples, horrified by what Judas has done, and not grasping the truth of Jesus’ plan, stone the supposed traitor to death. Even though the gospel decries martyrdom, it paradoxically also states that its subject was the first Christian martyr.

Resurrection of the Flesh by Luca Signorelli, circa 1500. According to 1 Corinthians 15: 52, “the trumpet shall sound, and the dead shall be raised incorruptible, and we shall be changed.”

4. Despite what mainstream Christian teachings preach, during the end times, resurrection of the faithful will not be physical but spiritual.

Only Judas is ready to hear the truth, so Jesus takes him aside and teaches him how the visible world we know is actually one of primeval darkness and disorder. But despair not: There’s a heavenly realm where the invisible Spirit of God dwells in an infinite cloud of light.

At a time when Christians believed that the apocalypse was going to happen in the near future and that the bodies of the faithful would be reanimated, the Gospel of Judas taught a controversial doctrine: The body is temporary, but the spirit is eternal.

Jesus said, “The souls of every human race will die. But when those (who belong to the holy race) have completed the time of the kingdom and the spirit separates from them, their bodies will die but their souls will be alive and they will be lifted up.

Gospel of Judas 8:1-4

That sounds suspiciously like the state of enlightenment at the heart of Buddhism, which was gaining favor around this time.

By the end of the gospel, Judas reaches enlightenment, er, comprehends Jesus’ teachings. No longer turning his eyes away from Jesus, he looks up and enters nirvana, er, that infinite cloud of light.

The torture and execution of Jesus, whom many believed would be another warrior king, dealt a severe blow to the faith of many early Christians. The Gospel of Judas attempts to show that the crucifiction (and murder of Judas) shouldn’t be disheartening: “This gospel suggests that our lives consist of more than what biology or psychology can explore — that our real life begins when the spirit of God tranforms the soul,” Pagels and King write.

A depiction of Lucifer devouring poor Judas

Was Judas a Demon?

Another scholar, April D. DeConick, offers a contradictory view. She questions the mainstream interpretation of the Gospel of Judas, arguing that instead of being the favored apostle, Judas was actually a demon.

That’s a misinterpretation of the Greek, according to Pagels and King. Jesus calls Judas the “thirteenth god,” using the word “daimon.” Of course this later developed a negative connotation, worming its way into our language as “demon.” But in Greek thought, the term indicated a lesser god or even an individual’s lot in life.

“Indeed,” the authors state, “Plato wrote that everyone possesses a daimon” — an idea picked up by Philip Pullman in the His Dark Materials series. –Wally