Evidence reveals that the Hyksos were Canaanites — and their story later morphed into the Exodus to serve as a rallying cry against Egypt.

Could over 600,000 Hebrew slaves revolt and escape their captors in Egypt? Spoiler alert: The Exodus is more folk tale than actual history.

Egyptian pharaohs steadily ruled their empire for thousands of years — except during a foreign occupation that lasted over a century.

An Egyptian historian named Mantheno, who wrote in the 3rd century BCE, “described a massive, brutal invasion of Egypt by foreigners from the east, whom he called Hyksos, an enigmatic Greek form of an Egyptian word that he translated as ‘shepherd kings’ but that actually means ‘rulers of foreign lands,’” write Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman in The Bible Unearthed: Archaeology’s New Vision of Ancient Israel and the Origin of Its Sacred Texts. Inscriptions and seals from the time of the invasion have names that are West Semitic, or Canaanite.

“If a great mass of fleeing Israelites had passed through the border fortifications of the pharaonic regime, a record should exist.”

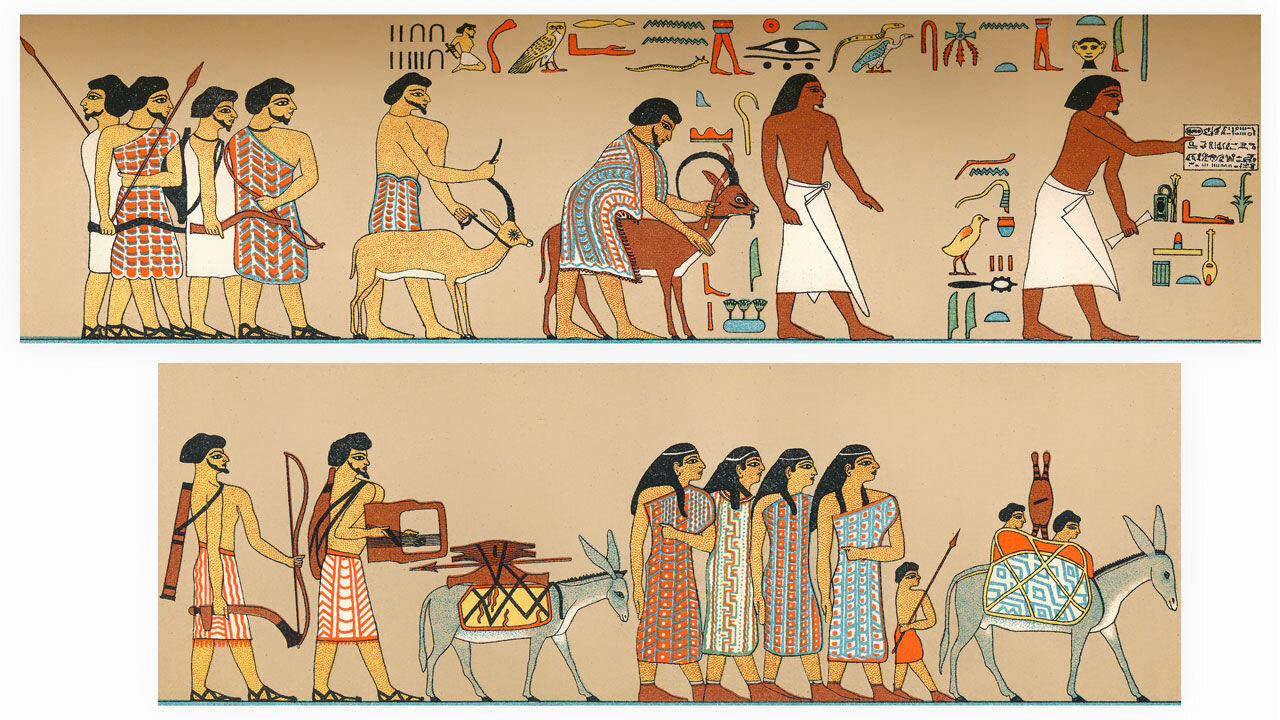

The Hyksos in this Egyptian painting are depicted as wearing brightly patterned clothes, which Wally much prefers to plain old white skirts.

Were the Hyksos Actually the Hebrews?!

Archaeological excavations in the eastern Nile delta “indicate that the Hyksos ‘invasion’ was a gradual process of immigration from Canaan to Egypt, rather than a lightning military campaign,” the authors write. “The fact that Manetho, writing almost fifteen hundred years later, describes a brutal invasion rather than a gradual, peaceful immigration should probably be understood on the background of his own times, when memories of the invasions of Egypt by the Assyrians, Babylonians and Persians in the seventh and sixth centuries BCE were still painfully fresh in the Egyptian consciousness.”

The biggest clue that the Hyksos were none other than the Hebrews is something else Manetho wrote: He suggests that after the usurpers were driven from Egypt, they founded the city of Jerusalem and built — you guessed it — an important temple there.

Israel gets a brief mention on the Merneptah Stele in a long list of conquered kingdoms.

When Did the Exodus Happen? The Merneptah Stele

If we take the story of the Exodus at face value for now, what evidence is there to provide a date for it? The Ancient Egyptians kept quite a written record, and, when paired with archaeological digs, the expulsion of the Hyksos is typically placed around 1570 BCE. If we go by the Old Testament account that this occurred 480 years after the construction of the Temple, that means the Exodus happened in 1440 BCE.

But the Bible mentions the Hebrew slaves helping to construct the city of Raames (Exodus 1:11) — a name that’s inconceivable at that time, according to Finkelstein and Silberman. “The first pharaoh named Ramesses came to the throne only in 1320 BCE — more than a century after the traditional biblical date,” they write. “As a result, many scholars have tended to dismiss the literal value of the biblical dating, suggesting that the figure 480 was little more than a symbolic length of time, representing the life spans of twelve generations, each lasting the traditional 40 years.”

The Battle of Kadesh, in which Ramesses II battled the Hittites, as shown on a wall of the Ramesseum, the pharaoh’s mortuary temple

A city named Pi-Ramesses, or the House of Ramesses, was built with the help of Semites in the delta during the reign of Pharaoh Ramesses II, who ruled from 1279-1213 BCE.

What’s more, though, is the famous stele of Merneptah, Ramesses’ son. The inscription is the sole mention of Israel in all of the artifacts from Ancient Egypt. The tribe is part of a list of people who were decimated during a Canaan campaign. Merneptah went so far to exclaim that Israel’s “seed is not!”

This would mean that if a historical Exodus did indeed take place, it would have occurred in the late 13th century. The evidence doesn’t match up, though.

The Israelites Leaving Egypt by David Roberts, 1828

The Exodus: A Lack of Evidence

It’s highly unlikely that a large group of slaves could have made it out of Egypt at the time, given the guard posts all along its borders, argue Finkelstein and Silberman. “If a great mass of fleeing Israelites had passed through the border fortifications of the pharaonic regime, a record should exist,” they insist.

And if the slaves did somehow get out, there would be archaeological records of the Hebrews as they wandered in the desert. “However, except for the Egyptian forts along the northern coast, not a single campsite or sign of occupation from the time of Ramesses II and his immediate predecessors and successors has ever been identified in Sinai,” write Finkelstein and Silberman. “And it has not been for a lack of trying.”

Numerous excavations haven’t turned up anything: “not even a single sherd, no structure, not a single house, no trace of an ancient encampment,” they continue. “One may argue that a relatively small band of wandering Israelites cannot be expected to leave material remains behind. But modern archaeological techniques are quite capable of tracing even the very meager remains of hunter-gatherers and pastoral nomads all over the world.”

Whether it actually happened or not, the Exodus makes for a great story — especially the dramatic parting of the Red Sea and the drowning of the pursuing Egyptians.

Dating Exodus — a Great Piece of Propaganda?

All of the archeological evidence, including a reference to the kingdom of Edom, which refuses to help Moses, indicates that the Exodus narrative was completed during Ancient Egypt’s Twenty-sixth Dynasty — that is, during the 7th and 6th centuries BCE (shortly after, one would imagine, the stories of Abraham and the other patriarchs told of in Genesis). That’s 600 years after the events were supposed to have taken place!

What was the purpose of the Exodus story, if we put it in context of that time in history? “The great saga of a new beginning and second chance must have resonated in the consciousness of the seventh century’s readers, reminding them of their own difficulties and giving them hope for the future,” Finkelstein and Silberman write.

Was Exodus written to bolster the agenda of King Josiah of Judah?

Josiah, the young ruler of Judah, sought to escape from the yoke of the newly crowned Pharaoh Necho II, who reigned Ancient Egypt from 610-595 BCE.

Connecting Josiah’s confrontation with the Egyptian empire to that of Moses and the pharaoh of Exodus, complete with miracle after miracle to demonstrate the Hebrews as Yahweh’s Chosen People, would have been a powerful piece of propaganda.

“[A]ncient traditions from many different sources were crafted into a single sweeping epic that bolstered Josiah’s political aims,” the authors conclude.

There simply is no evidence that a mass Exodus as described in the Old Testament ever happened. –Wally