Once home to many Gullah families, this South Carolina Sea Island has a rich history, including the Yamasee War in Bloody Point and the once-thriving Daufuski Oysters business.

A wedding at the Union Baptist Church. Daufuskie Island was once home to hundreds of Gullah — but only 12 or so remain today.

Part of Daufuskie’s charm lies in its unspoiled landscape. Gnarled limbs of old growth live oaks dripping with Spanish moss. Outlying marshes of Spartina grass rustling in the wind. Many of its roads are still unpaved, which is one of the reasons we were unable to visit last year due to heavy rainfall.

The South Carolina Sea Island, situated between Hilton Head Island and Savannah, Georgia, has many dilapidated historic properties — but there are also a couple of newer gated communities, including the upscale Haig Point and Bloody Point, which are strictly off limits to non-residents. The island was once mostly populated by Gullah, African American descendants of slaves living in South Carolina (and called Geechee in Georgia). Nowadays, less than a third of the homes on Daufuskie are owned by the original Gullah families — and only 12 or so Gullah actually still live there.

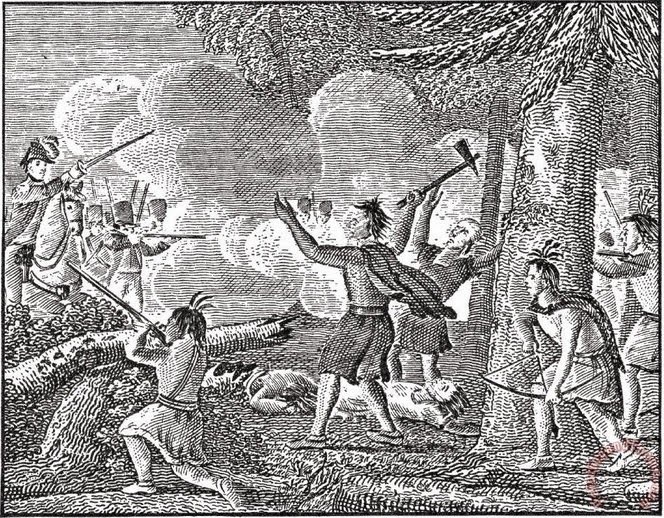

“The Yamasee War was a massacre, as native weaponry was no match for European firepower — which is how the neighborhood Bloody Point got its name. ”

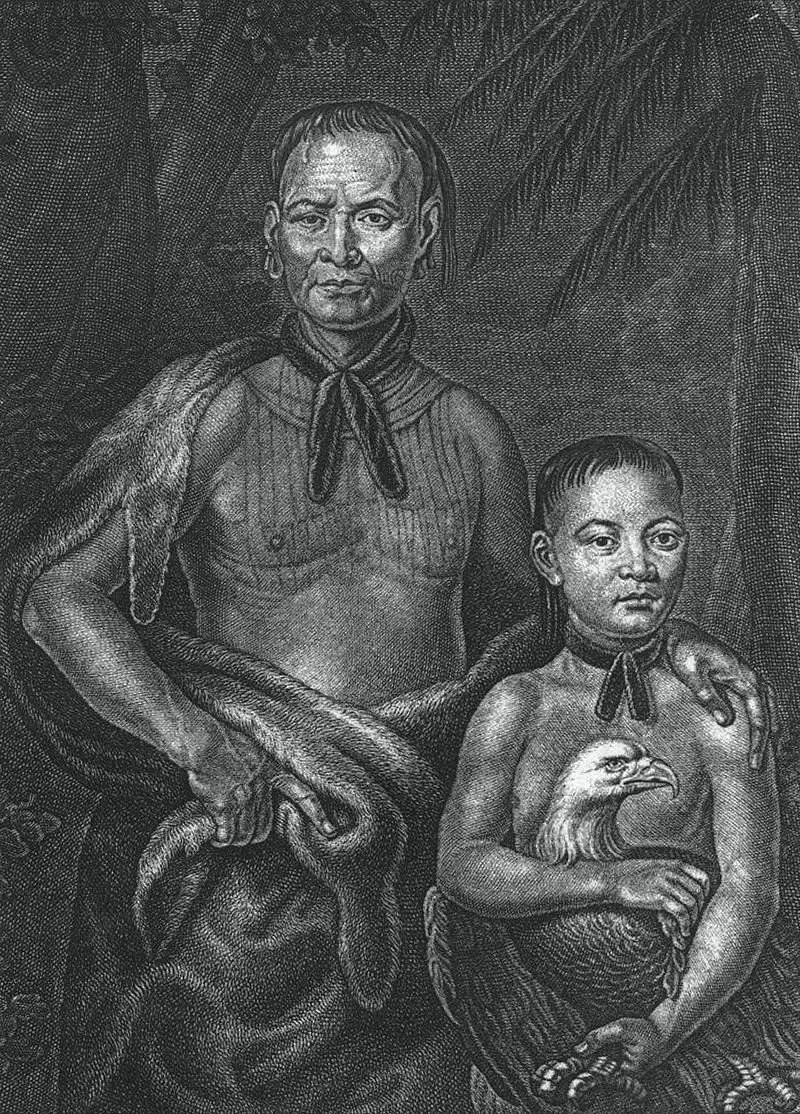

Chief Tamochichi, with his nephew, of the Yamacraw, a native tribe composed of Creek and Yamasee. (Incidentally, when Pat Conroy wrote about Daufuskie in this memoir, The Water Is Wide, he changed the island’s name to Yamacraw (but he wasn’t fooling anybody.)

The First Inhabitants: A Deal With Spain

In the 1500s, the Muscogee (aka Creek) native tribe encountered the invading Spaniards, who claimed the Atlantic coast spanning from St. Augustine, Florida to Charleston, South Carolina. However, when they stopped on Daufuskie, they decided that this wasn’t an ideal place to start a new colony. They left a few Iberian horses known as the Carolina Marsh Tacky and made a deal with the Muscogees. If the natives were to fend off any other Europeans looking to colonize the area, the Spaniards would back them up with military support and pay them in gold.

Despite the Spanish promising they’d help the Native Americans fend off other European invaders, they abandoned them to the British.

The Yamasee War: How Bloody Point Got Its Name

Time passed, and the next two centuries had little effect on the natives, until the English established a colony on Daufuskie. Suffice to say, the Spanish didn’t keep their word in offering support and were nowhere to be found.

Inevitably, conflict arose, in part because the British settlers believed it was their sovereign right to claim the land. And while the indigenous Muscogee and Yemassee traded food, animal hides and local knowledge for knives, copper kettles and beads, the exchange rate wasn’t deemed fair.

Tomahawks and bows were no match for the British army’s guns. The Yamasee War resulted in the slaughter of the indigenous people.

This prompted the Yamasee, who inhabited the nearby coastal region of Georgia, to join the Creek in attacking the British settlers. The raids turned into massacres, as native weaponry was no match for European firepower — which is how the neighborhood Bloody Point got its name.

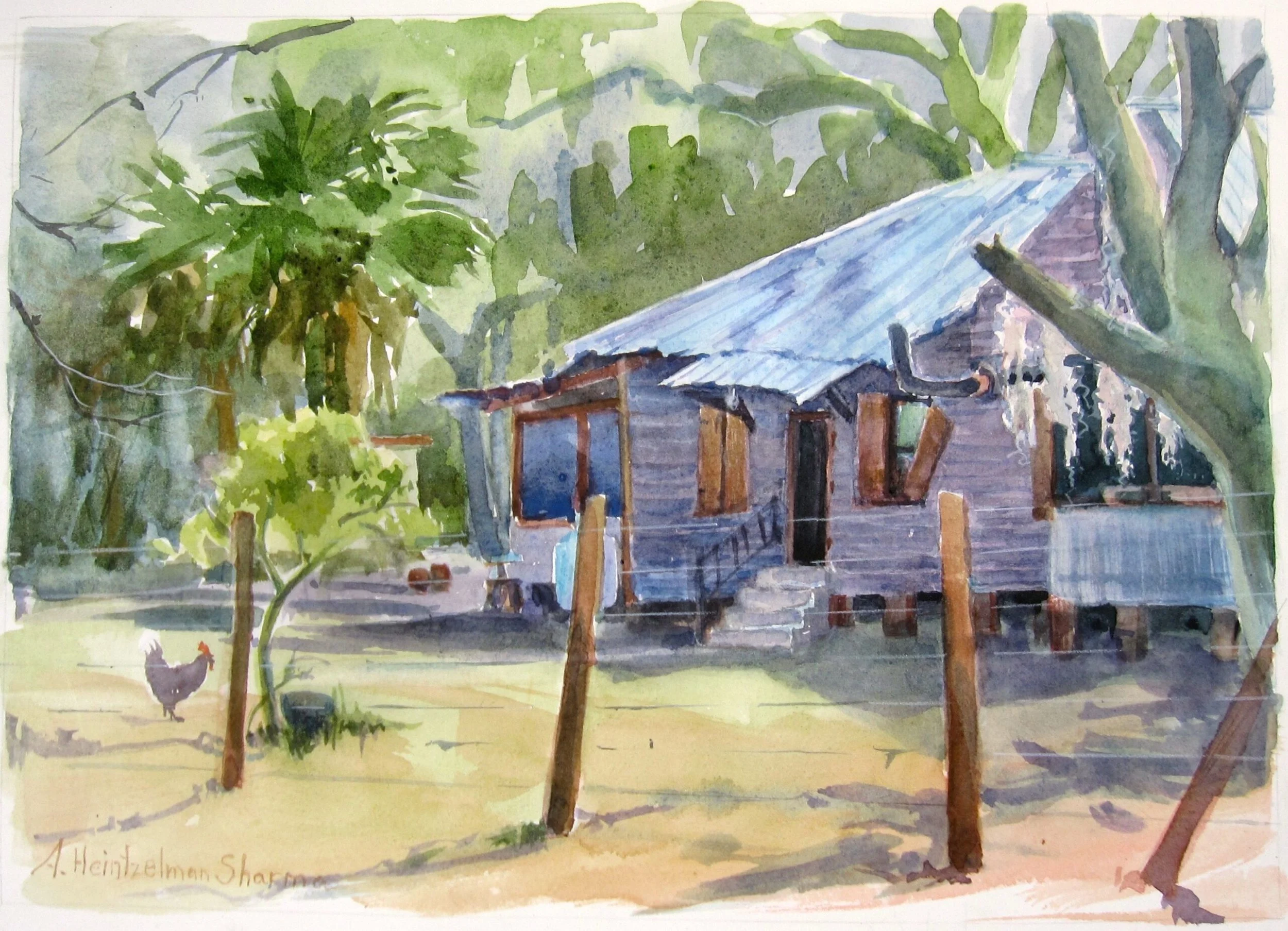

A small one-room wooden home known as a single pen house on Daufuskie

The Rise of Slave Labor

After the war ended, English settlers cleared the island of vegetation to cultivate crops. They also divided the island into 11 plantations. According to our guide Ryland, with Tour Daufuskie, it was so thoroughly cleared, it was said that you could see from one end of Daufuskie to the other — a depressing fact given that the island is five miles long and two and a half miles wide.

The British brought slaves from the Rice Coast of West Africa as well as Central Africa. European settlers relied on the skills of the enslaved to cultivate rice, cotton and indigo, resulting in some of the wealthiest antebellum plantations in the South.

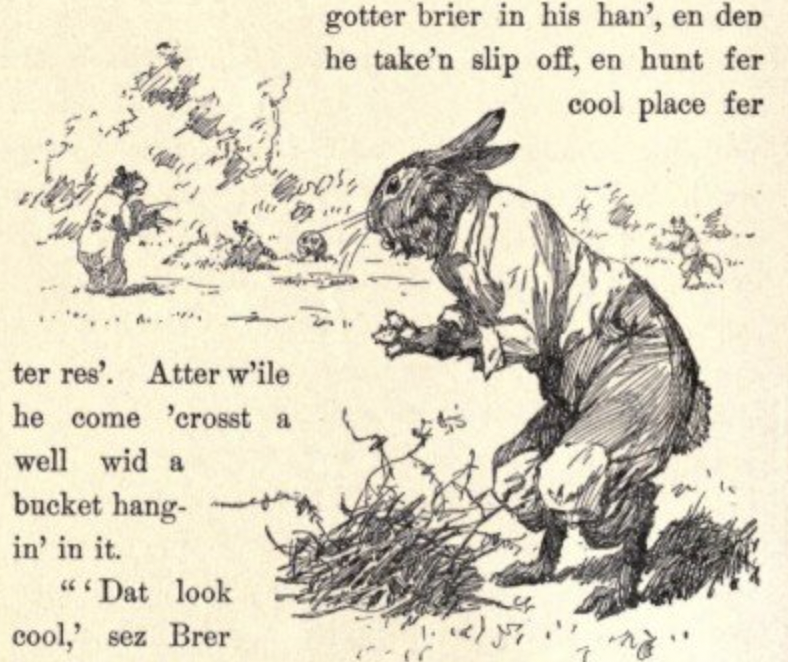

Over time, the enslaved Africans developed a dialect also called Gullah. The vocabulary and grammatical roots came from English and African languages. Isolated from the mainland, the Gullah maintained African traditions, culture and religion. Gullah is a living language that’s still spoken in the region.

The Uncle Remus stories, including the tales of Brer Rabbit, were written in Gullah.

The British tried growing rice and sugarcane — crops that had flourished on nearby Hilton Head. But because Daufuskie is at a higher altitude, its ground-water levels were too low to sustain these lucrative crops for export.

Indigo was the first profitable commercial crop and a significant part of the economy for about 50 years, followed by Sea Island cotton. The indigo plant was grown to produce a royal blue dye that was exported to England. “If it had ‘royal’ in the name, they were gonna buy it,” Ryland said.

The spongey palmetto logs used to build Fort Moultrie helped absorb cannon fire from the British armada.

Why South Carolina Is the Palmetto State

Throughout the Revolutionary War, South Carolina remained loyal to England. Part of this was an economic motivation: The colonists believed their defeat would end the demand for indigo. However, as the British fleet got closer, the settlers realized it didn’t matter whether or not they were loyalists; they would still be attacked.

To defend Charleston harbor, the colonists built Fort Moultrie on Sullivan’s Island from the palmetto, or cabbage palm. The name cabbage palm comes from the fact that the heart of the palm can be eaten raw or can be cooked into what was known by early settlers as swamp cabbage.

Palmetto isn’t a traditional type of wood. It’s soft, doesn’t splinter and is almost sponge-like due to its high water content. Fort Moultrie had two walls of palmetto logs and sand, a combination that worked well at absorbing cannonballs fired at it by British ships. This unique wood helped save South Carolina, which became the Palmetto State, and the tree now has a place of honor on the state flag.

After the war ended, England did indeed stop importing indigo from South Carolina. They basically said, if you’re not part of our kingdom, we don’t want your indigo. The crown had a new colony in India, and to this day, India is the world’s top producer of indigo.

However, England did continue to purchase Sea Island cotton because it was just rare enough that they couldn’t be very picky about where they got it from. Freed slaves who lived on the island grew cotton through the Civil War, until fields were ruined by the boll weevil.

Out Back Daufuskie Way by Alexandra Sharma

From Reparations to Sharecropping

Union forces captured Daufuskie in 1861. Their main job was to keep track of the ships going in and out of the Savannah River and ensure that no weapons, food or ammunition reached the Southern states. Plantation owners fled, leaving behind their property as well as their elderly slaves, who weren’t deemed worth the expense to relocate.

After the Emancipation Proclamation, Daufuskie was home to a large population of freed slaves who had worked on the island’s plantations. As a form of reparation, slaves received 40 acres and a mule, land abandoned by White colonists throughout the South.

However, President Andrew Johnson intervened, ordering most of the land to be returned to its former owners. Despite having settled the land, the Gullah on Daufuskie had to switch to sharecropping, a system where the landowner allowed use of the land in exchange for crops. The situation wasn’t unlike serfdom, tying the Gullah to the land and trapping them into high debts.

The oyster industry employed Daufuskie residents in its heyday. When the oyster beds were polluted from a nearby paper mill, most islanders left — never to return.

Aw Shucks: When the World Was Their Oyster

Indigo and cotton weren’t the only lucrative industries on the island. L.P. Maggioni & Company established an oyster cannery on Daufuskie in 1894 and employed many Gullah men, women and even children. Containers with the distinctive profile of an Indian chief on its label can be seen in the Daufuskie Island History Museum.

Gullah men went out on the water in bateaux, flat-bottomed wooden boats, during low tide to pluck up all the oysters they could haul back. It was the women who shucked the oysters, though — up to 7 to 9 gallons a day.

While the men went out in the boats to gather oysters, it was women (and children) who had to shuck them all.

Even though the local cannery closed in the 1950s, you can still get Daufuski Brand Oysters — they just come from Korea now.

There was a cannery on the island from 1898 to 1956. Around that time, wood pulp waste from a paper mill on the Savannah River polluted the water and contaminated the oyster beds. With the closing of the factory, most families left for better opportunities in nearby Savannah.

Daufuski Oysters are still available — they’re just harvested in Korea.

Some of the Gullah homes on Daufuskie are available as vacation rentals as part of a program to preserve them.

Heirs’ Properties on Daufuskie

As we drove around the island in a golf cart, we noticed wood-framed homes sitting among the vegetation in varying states of disrepair. We asked Ryland about them, and he informed us that they’re historic Gullah homes known as oyster cottages. Referred to as “heirs’ properties,” these homes are passed down from generation to generation without legal documentation. Most Gullah never returned to Daufuskie, but all heirs have the same claim to the property, whether or not they live on it, pay taxes on it or have ever set foot on it. Because so many people can be involved, it’s tough to sell or restore one of the homes since everyone must agree on the course of action. As a result, many of the oyster cottages have become dilapidated.

Enter the nonprofit Palmetto Trust for Historic Preservation (now Preservation South Carolina), which developed the Daufuskie Endangered Places Program in 2011. The initiative was funded in part through a grant provided by the 1772 Foundation, an organization whose mission is to preserve historic properties. The trust’s first project was to restore the Frances Jones House.

It’s a cool program: Descendants retain ownership under a long-term lease with the preservation group. Restored cottages are available as vacation rentals. Once the lease is paid off, the homes revert back to the heirs. By staying on Daufuskie Island, you’re helping preserve its history.

The haunted-looking Melrose Resort on Daufuskie, long abandoned after its owners swindled investors out of millions and declared bankruptcy.

Financial Fraud at Melrose Landing

In the modern era, Daufuskie has developed some high-end gated communities. But even the best-laid plans can go awry. Case in point: Melrose Landing. The namesake resort was developed in the 1980s and included an inn, beach cottages, a Jack Nicklaus-designed golf course and a ferry landing.

The resort was purchased in 2011 by Utah-based developer Pelorus Group, which, over eight years, proceeded to defraud its investors. The real estate firm ran a dubious Ponzi-like scheme, including wire and tax fraud, using $1.8 million of investor money for personal use without disclosing any of it to the IRS. The vacation property first filed for bankruptcy in 2009 and again in 2017, when the firm’s managing partner, James Thomas Bramlette, was indicted. In the end, the Pelorus Group owed creditors about $35 million. The derelict resort is currently seeking an investor willing to put up $19 million in cash. Any takers?

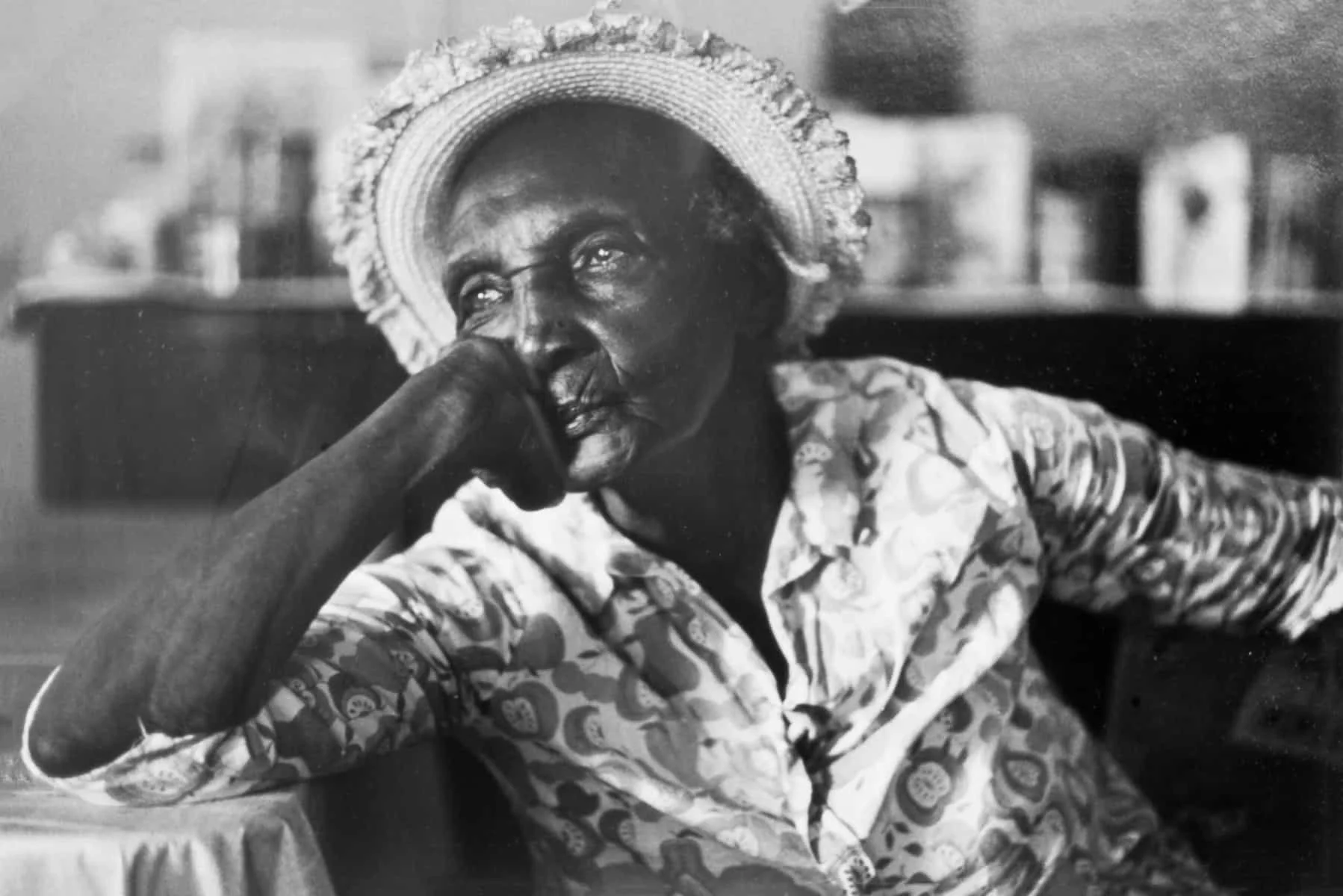

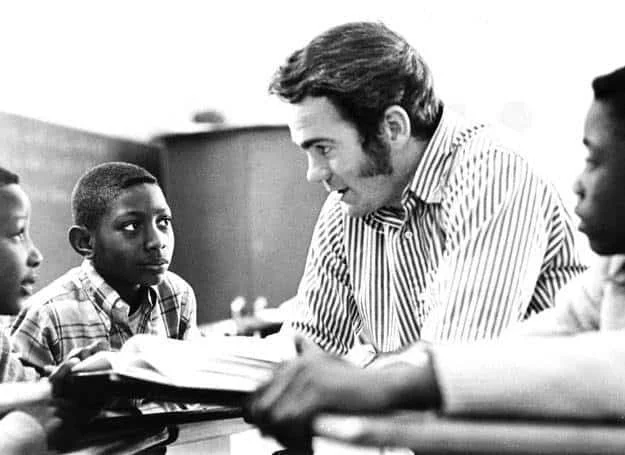

The following photos were taken by Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe from 1977 to 1982. At the time, less than 85 permanent residents lived in the 50-some homes on Daufuskie. The island’s amenities consisted of a co-op store, a two-room school, a nursery, a church and two active cemeteries.

An Old Woman Sitting at a Table in Her Home by Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe

Susie Sanding Next to a Holy Picture in Her Living Room by Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe

A Shrimper and His Son by Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe

Boiling Crab by Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe

Daufuskie’s Rich but Tragic History: Hope for the Future

Daufuskie has a turbulent history: bloody battles, mistreatment of slaves, the lost oyster industry. It once bustled with activity and commerce, but now few Gullah people remain. In fact, much of the island is home to wealthy White residents living in private gated communities such as Haig Point and Bloody Point.

But by learning about and visiting the island, we can help preserve a vibrant heritage. And thanks to Preservation South Carolina and others like them, future generations of Gullah families might someday be able to return to the island. –Duke

Check out those sideburns on Conroy!

READ ON: Daufuskie Island Tour: Learn about bestselling author Pat Conroy’s connection to the island, see the historic sites and meet some local artisans.