A Jean de la Fontaine fable helped the noisome cicada bug burrow its way into Provençal hearts.

The noisy (and let’s face it, rather ugly) bug the cicada became the chosen motif to represent the French region of Provence

Aix-en-Provence, France has all the trappings of a charming Provençal town, in particular its farmers markets filled with fresh produce, assorted cheeses, lavender sachets and freshly cut sunflowers. What we didn’t expect to find depicted everywhere was cicadas. There were brightly glazed ceramic ones, table linens with their likeness and pastel-colored cicada-shaped soaps. You can imagine our surprise and delight, when Wally and I learned that the people of Provence chose cicadas (which I call “ree-ree bugs” because of the sound they make) as their honorary symbol. We had to discover how this came about.

When summer arrives in Provence, cicadas, or cigales as they are referred to in French, dramatically announce their return, filling the air with their distinctive melody.

“According to Provençal folklore, the cicada was sent by God to rouse peasants from their afternoon siestas to prevent them from becoming too lazy.

The plan backfired.”

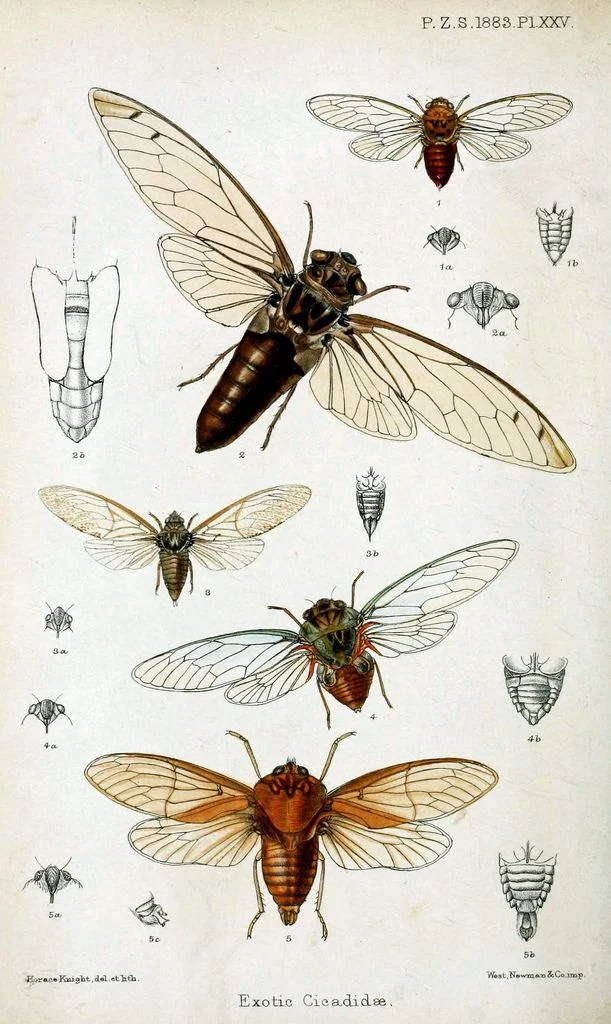

Cicadas have been featured in literature since ancient times. Greek poets were compelled to write odes to them. To them, cicadas symbolized death and rebirth, due to the bugs’ mysterious life cycle. Cicadas spend their nymph stage underground, and classical poets likely observed species that buried themselves for two to five years before emerging from the earth.

Only the male cicada “sings,” prompting the Ancient Greek poet Xenophon to quip: “Blessed are the cicadas, for they have voiceless wives.”

When the air reaches the right temperature — 77ºF — masses of male cicadas will stridently whine or serenade female cicadas; the females do not sing. For those more poetically inclined, each sings in unison by rapidly vibrating their tymbal, a thin membrane with thickened ribs located on each side of its abdomen. Because the abdomen is mostly hollow, it acts as a resonance chamber that amplifies the sound and broadcasts up to mile away. The din is the loudest of all insect-produced sounds.

In Phaedrus, Plato muses that cicadas were once men who became so enraptured by music, they forgot to eat and drink, and their bodies wasted away

According to Provençal folklore, the cicada was sent by God to rouse peasants from their afternoon siestas on hot summer days and prevent them from becoming too lazy. The plan backfired: Instead of being disturbed by the cicada, the peasants found the sound of their buzzing relaxing, which in turn lulled them to sleep.

There is a Provençal expression: Il ne fait pas bon de travailler quand la cigale chante, or “It’s not good to work when the cicada is singing.”

Jean de la Fontaine’s story “The Cicada and the Ant” is based on one of Aesop’s famous fables

Jean de la Fontaine wrote the fable “La Cigale et la Fourmi” (“The Cicada and the Ant”) in 1668, an interpretation inspired by Aesop’s “The Ant and the Grasshopper.” In the story, the cicada passes the glorious days of summer consumed in song, while the industrious ant forages and stores food for the winter to come.

The ant works industriously all summer long, while the cicada lazes about singing. Guess who’s caught off-guard when winter arrives?

In 1854, together with six other local writers, Frédéric Mistral formed the Félibrige, a literary society to preserve the Provençal language and customs of Southern France. He coined the phrase, “Lou soulei mi fa canta,” Provençal for “the sun makes me sing,” usually accompanied by an illustration of a cicada.

A ceramicist from the Aubagne town of Provence, Louis Sicard, was asked by a wealthy tile manufacturer in 1895 to come up with a small keepsake gift symbolizing Provence for the man to give to his business clients. Inspired by the poets of the Félibrige, Sicard designed and created a paperweight with a cicada sitting on an olive branch bearing Mistral's epigram “Lou soulei mi fa canta,” earning himself the nickname “the Father of the Cicadas.”

If you startle a cicada, it might emit a spray of piss, prompting Provençal peasants of the past to thread the insects on a string, hang them up to dry and then boil their bodies into a tisane to cure urinary tract ailments

The people of Provence adopted the noisy critters as their mascot, and the motif made its way into everything from regional fabrics to pottery displayed proudly outside Provençal homes. Like horseshoes or four leaf clovers, they’re regarded as good luck charms, and seem to burrow their way into many a tourist’s suitcase. In fact, we purchased a wrought-iron cicada trivet at the Isle-sur-la-Sorgue market and a bunch of perfumed ceramic cicadas at the Aix tourist center as souvenirs and gifts. –Duke